News + Media

Like a lot of economists, Christopher Knittel entered college with career plans in mind. Unlike a lot of economists, Knittel had plans that involved baseball. At California State University at Stanislaus, Knittel was good enough to make the team as a second baseman. But during his freshman season, reality sank in.

“I quickly learned the pros weren’t in my future,” says Knittel, a lifelong Oakland A’s fan who played baseball recreationally until his mid-30s.

Christopher Knittel

Photo: M. Scott Brauer

For a while in college, Knittel also considered becoming an attorney. But then, he says, “I took my first economics course and fell in love with it. Economics teaches you how to think and you constantly see real-world examples of the concepts you’re learning.”

Today, Knittel is the William Barton Rogers Professor of Energy Economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management, having joined MIT earlier this year. He is known for inventive, heavily empirical work largely focusing on energy and transportation, although he has studied electricity markets and corporate strategies as well.

Knittel’s research addresses a clutch of practical and linked questions: How much progress have automakers made on fuel efficiency? (More than you might think.) How do car owners respond when fuel prices rise? (They really do ditch their gas-guzzlers.) How large are the collateral health benefits of removing dirty vehicles from the nation’s fleet? (Very large.)

All told, Knittel has produced concrete findings that he hopes will have an impact in the halls of Washington. “A lot of energy policies that we have are not the most efficient policies,” he says. “I want to inform policymakers what the true costs and benefits of certain policies are.”

Detroit: Actually more fuel-efficient

Knittel mostly grew up in Northern California, where his father was an engineer for Peterbilt, the truck manufacturer. In addition to baseball, he developed a liking for cars and learned to replace the engine in his Ford Mustang while in high school.

After getting his undergraduate degree, Knittel (pronounced with a hard “k”) received his M.A. in economics from the University of California at Davis, then got his PhD in economics from the University of California at Berkeley in 1999, after his graduate adviser, Severin Bornstein, moved from Davis to Berkeley. Knittel taught for three years at Boston University before returning to U.C. Davis, where he remained until joining MIT.

“A lot of my work draws on the hard sciences,” says Knittel, 39. “Davis was great, but there’s no place like MIT, in terms of the opportunities to do quality interdisciplinary work.”

In a sense, Knittel is still looking under the hoods of cars. One of his papers, “Automobiles on Steroids,” recently published in the American Economic Review, examines technological progress in the auto industry. From 1980 through 2006, the fuel efficiency of America’s vehicles has increased by just 15 percent — at first glance, a lethargic rate of improvement. But as Knittel points out, cars’ average horsepower has roughly doubled since then, and average curb weight of those vehicles rose 26 percent during that time. Adjusting for these changes, fuel economy has actually increased by 60 percent since 1980, but as Knittel observes, “most of that technological progress has gone into [compensating for] weight and horsepower.”

On the stagnation of overall fuel efficiency since 1980, Knittel adds, “It’s no fault of the manufacturers and consumers. Firms are going to give consumers what they want, and if gas prices are low, consumers are going to want big, fast cars. If you’re going to blame anyone, it’s the policymakers for not creating the incentive structure for putting that technological progress into fuel economy.”

Pain at the pump

Cars and light trucks produce about 15 percent of U.S. greenhouse gases. The best policy for reducing energy consumption from those sources, Knittel believes, would be higher fuel prices. “That would incentivize all the things we want,” Knittel says. “When gas prices go up, people shift to more fuel-efficient cars, they drive fewer miles, and insofar as there are lower-carbon-intensive fuels out there, people shift to them. They get rid of their clunkers faster.”

That’s not just an assumption; Knittel has studied the responses of auto owners nationwide to rising gas prices from 1999 to 2008 in another research paper, “Pain at the Pump,” co-authored with Meghan Busse and Florian Zettelmeyer of Northwestern University. The researchers found that with each $1 rise in the price of gas, purchases of highly fuel-efficient autos increase 21 percent, while purchases of gas-guzzling vehicles drop 27 percent.

A shift to newer, more fuel-efficient vehicles would actually help people in another way, besides releasing fewer greenhouse gases: It would reduce the amount of harmful local pollution in the air, as Knittel detailed in a paper written with Ryan Sandler of U.C. Davis, based on a study of California from 1998 to 2008. “When gas prices go up, you’re getting bigger mileage reductions from cars that are worse in terms of these pollutants,” Knittel observes.

That produces significant health benefits beyond the problems associated with climate change. “We’re talking about asthma attacks and respiratory problems,” he adds. “This isn’t just a matter of helping the world two generations from now. You can point to this and say, ‘Here is a more immediate, salient reason for a gas tax.’” According to Knittel and Sandler, 70 percent of the costs of a gas tax of $1 per gallon could be recouped by immediate health benefits from reduced pollution. Other possible benefits from the tax — reductions in climate change, traffic congestion and accidents — could make it a net winner for people in economic terms alone.

But will politicians ever impose higher gas prices on a financially stretched public? A variety of powerful lobbying interests in Washington oppose such a move — and Knittel knows hardball when he sees it. Indeed, Knittel is examining the financial rewards industries reap from their lobbying efforts in some of his current research. Still, he does retain a sense of optimism. “The idealistic academic in me says that the more you broadcast the truth, the more likely it will be to win out,” Knittel says. “But we’ll see.”

Christopher Knittel had big dreams heading into college. Those dreams involved baseball.

Today’s global challenges will significantly affect how we grow our food. But these challenges are so complex and intertwined that response measures require collaboration and a broad, integrated lens.

By: Jennifer Chu

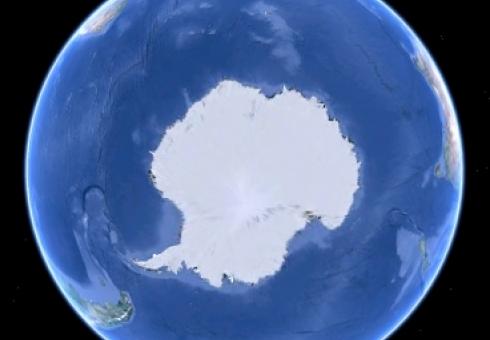

The world’s oceans act as a massive conveyor, circulating heat, water and carbon around the planet. This global system plays a key role in climate change, storing and releasing heat throughout the world. To study how this system affects climate, scientists have largely focused on the North Atlantic, a major basin where water sinks, burying carbon and heat deep in the ocean’s interior.

But what goes down must come back up, and it’s been a mystery where, and how, deep waters circulate back to the surface. Filling in this missing piece of the circulation, and developing theories and models that capture it, may help researchers understand and predict the ocean’s role in climate and climate change.

Recently, scientists have found evidence that the missing piece may lie in the Southern Ocean — the vast ribbon of water encircling Antarctica. The Southern Ocean, according to observations and models, is a site where strong winds blowing along the Antarctic Circumpolar Current dredge waters up from the depths.

“There’s a lot of carbon and heat in the interior ocean,” says John Marshall, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Oceanography at MIT. “The Southern Ocean is the window by which the interior of the ocean connects to the atmosphere above.”

Marshall and Kevin Speer, a professor of physical oceanography at Florida State University, have published a paper in Nature Geoscience in which they review past work, examine the Southern Ocean’s influence on climate and draw up a new schematic for ocean circulation.

A revised conveyor

For decades, a “conveyor belt” model, developed by paleoclimatologist Wallace Broecker, has served as a simple cartoon of ocean circulation. The diagram depicts warm water moving northward, plunging deep into the North Atlantic; then coursing south as cold water toward Antarctica; then back north again, where waters rise and warm in the North Pacific.

However, evidence has shown that waters rise to the surface not so much in the North Pacific, but in the Southern Ocean — a distinction that Marshall and Speer illustrate in their updated diagram.

Marshall says winds and eddies along the Southern Ocean drag deep waters — and any buried carbon — to the surface around Antarctica. He and Speer write that the updated diagram “brings the Southern Ocean to the forefront” of the global circulation system, highlighting its role as a powerful climate mediator.

Indeed, Marshall and Speer review evidence that the Southern Ocean may have had a part in thawing the planet out of the last Ice Age. While it’s unclear what caused Earth to warm initially, this warming may have driven surface wind patterns poleward, pulling up deep water and carbon — which would have been released into the atmosphere, further warming the climate.

Shifting winds

In a cooling world, it appears that winds shift slightly closer to the Equator, and are buffeted by the continents. In a warming world, winds shift toward the poles; in the Southern Ocean, unimpeded winds whip up deep waters. The researchers note that two manmade atmospheric trends — ozone depletion and greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels — have a large effect on winds over the Southern Ocean: As the ozone hole recovers, greenhouse gases rise and the planet warms, winds over the Southern Ocean are likely to shift, affecting the delicate balance at play. In the future, if the Southern Ocean experiences stronger winds displaced slightly south of their current position, Antarctica’s ice shelves may be more vulnerable to melting — a phenomenon that may also have contributed to the end of the Ice Age.

“There are huge reservoirs of carbon in the interior of the ocean,” Marshall says. “If the climate changes and makes it easier for that carbon to get into the atmosphere, then there will be an additional warming effect.”

Jorge Sarmiento, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at Princeton University, says the Southern Ocean has been a difficult area to study. To fully understand the Southern Ocean’s dynamics requires models with high resolution — a significant challenge, given the ocean’s size.

“Because it’s so hard to observe the Southern Ocean, we’re still in the process of learning things,” says Sarmiento, who was not involved with this research. “So I think this is a very nice snapshot of our current understanding, based on models and observations, and it will sort of be a touchstone for future developments in the field.”

Marshall and Speer are now working with a multi-institution team led by MIT’s collaborator, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, to measure how waters upwell in the Southern Ocean. The researchers are studying the flow driven by eddies in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, and have deployed tracers and deep drifters to measure its effects; temperature, salinity and oxygen content in the water also help tell them how eddies behave, and how quickly or slowly warm water rises to the surface.

“Any perturbation that is made to the atmosphere, whether it’s due to glacial cycles or ozone or greenhouse forcing, can change the balance over the Southern Ocean,” Marshall says. “We have to understand how the Southern Ocean works in the climate system and take that into account.”

China's worsening air pollution, after decades of unbridled economic growth, cost the country $112 billion in 2005 in lost economic productivity, a study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has found.

China's worsening air pollution, after decades of unbridled economic growth, cost the country $112 billion in 2005 in lost economic productivity, a study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has found.

The figure, which also took into account people's lost leisure time because of illness or death, was $22 billion in 1975, according to researchers at the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.

The study, published in the journal Global Environmental Change, measured the harmful effects of two air pollutants: ozone and particulates, which can lead to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

"The results clearly indicate that ozone and particulate matter have substantially impacted the Chinese economy over the past 30 years," one of the researchers, Noelle Selin, an assistant professor of engineering systems and atmospheric chemistry at MIT, said in a statement.

Ground-level ozone is produced by chemical plants, gasoline pumps, paint, power plants, motor vehicles and industrial boilers. Inhaling it can result in inflammation of the airways, coughing, throat irritation, discomfort, chest tightness, wheezing and shortness of breath.

Past studies have shown that high daily ozone concentrations are accompanied by increased asthma attacks, hospital admissions, mortality, and other markers of disease.

Particulates -- spewed out by power plants, industries and automobiles -- are microscopic solids and droplets so tiny they penetrate deep into the lungs and can even get into the bloodstream.

Lengthy exposure can result in coughing, breathing difficulties, impaired lung function, irregular heartbeat and premature death in people with heart or lung disease.

MORE DAMAGING THAN THOUGHT

The researchers made their calculations using atmospheric modeling tools and global economic modeling, which were useful in assessing the impact of ozone, that China started monitoring only recently. Using this methodology, they were able to simulate historical ozone levels.

Kelly Sims Gallagher, an associate professor of energy and environmental policy at Tufts University's Fletcher School, who was not involved in the study, said the findings revealed the problem was even worse than thought.

"This important study confirms earlier estimates of major damages to the Chinese economy from air pollution, and in fact, finds that the damages are even greater than previously thought," Gallagher said.

China is a large emitter of mercury, carbon dioxide and other pollutants. In the 1980s, China's particulate concentrations were 10 to 16 times higher than the World Health Organization's annual guidelines, the researchers said.

Even after significant improvements by 2005, the concentrations were five times higher than what is considered safe.

Chinese authorities are aware of the devastating effects of the degradation to the environment and are taking steps to tackle it.

This month, authorities announced plans to reduce air pollution by 15 percent in the capital, Beijing, by 2015, and 30 percent by 2020 through phasing out old cars, relocating factories and planting new forests.

SOURCE: Andy Wong, AP

By: Wendy Koch

China's unprecedented growth is carrying a steadily steeper price tag as its air pollution hikes the nation's health care costs, finds a new study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Although China has made substantial progress in reducing its air pollution, MIT researchers say its economic impact has jumped from $22 billion in 1975 to $112 billion in 2005. The costs result from both lost labor and the increased need for health care because ozone and particulates in air can cause respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

"The results clearly indicate that ozone and particulate matter have substantially impacted the Chinese economy over the past 30 years," Noelle Selin, an assistant MIT professor of engineering systems and atmospheric chemistry, said in announcing the findings that appear in the February edition of the journal Global Environmental Change.

The study, by researchers at the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, said pollution's economic impact has grown, because population growth increased the number of people exposed to it and higher incomes raised the costs associated with lost productivity.

The study "finds that the damages are even greater than previously thought," said Kelly Sims Gallagher, an associate professor of energy and environmental policy at Tufts University's Fletcher School, in the MIT announcement.

The researchers calculated these long-term impacts using atmospheric and economic modeling tools, which were especially important when it came to assessing the cumulative impact of ozone. They said China has only recently begun to monitor ozone , and it's become the world's largest emitter of mercury, carbon dioxide and other pollutants.

In the 1980s, they said China's particulate-matter concentrations were at least 10 to 16 times higher than the World Health Organization's annual guidelines. Even after major improvements, by 2005, they said the concentrations were still five times higher than what is considered safe and led to 656,000 premature deaths in China each year.

China is taking steps to mitigate air pollution, in partly by boosting its support for renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. Its hefty subsidies to its solar industry have prompted some U.S. manufacturers to file a complaint with the International Trade Commission. In January, the nation set a target to reduce its 2010 levels of carbon intensity (the amount of carbon emitted per unit of gross domestic product) 17% by 2015.

Despite improvements in air quality, the economic impact of air pollution has increased dramatically, new MIT study shows.

By: Vicki Ekstrom, Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change

Although China has made substantial progress in cleaning up its air pollution, a new MIT study shows that the economic impact from ozone and particulates in its air has increased dramatically.

Although China has made substantial progress in cleaning up its air pollution, a new MIT study shows that the economic impact from ozone and particulates in its air has increased dramatically.In recent decades, China has experienced unprecedented growth. But that growth comes with a steep price tag, according to the study, which appears in the February edition of the journal Global Environmental Change. The study, by researchers at the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, analyzes the costs associated with health impacts from ozone and particulate matter, which can lead to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

Quantifying costs from both lost labor and the increased need for health care, the study finds that this air pollution cost the Chinese economy $112 billion in 2005. That’s compared to $22 billion in such damages in 1975.

“The results clearly indicate that ozone and particulate matter have substantially impacted the Chinese economy over the past 30 years,” even though there have been significant improvements in air quality detected over this period, says Noelle Selin, an assistant professor of engineering systems and atmospheric chemistry at MIT.

The researchers discovered this large economic impact because they looked at pollution’s long-term effect on health, not just the immediate costs. In doing so, they found two main causes for the increase in pollution’s costs: rapid urbanization in conjunction with population growth increased the number of people exposed to the pollution, and higher incomes raised the costs associated with lost productivity.

“This suggests that conventional, static methods that neglect the cumulative impact of pollution-caused welfare damage or other market distortions substantially underestimate pollution's health costs, particularly in fast-growing economies like China,” says Kyung-Min Nam, one of the study’s authors and a postdoc in the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.

Nam gives one example from the study showing that pollution led to a $64 billion loss in gross domestic product in 1995. That compares to static estimates from the World Bank that found the loss to be only $34 billion.

In this way, Selin says, “this study represents a more accurate picture than previous studies.”

Kelly Sims Gallagher, an associate professor of energy and environmental policy at Tufts University’s Fletcher School, agrees: “This important study confirms earlier estimates of major damages to the Chinese economy from air pollution, and in fact, finds that the damages are even greater than previously thought.”

The researchers calculated these long-term impacts using atmospheric modeling tools and comprehensive global economic modeling. These models proved especially important when it came to assessing the cumulative impact of ozone, which China has only recently begun to monitor. Using their models, the MIT researchers were able to simulate historical ozone levels.

China has become the world’s largest emitter of mercury, carbon dioxide and other pollutants. In the 1980s, China’s particulate-matter concentrations were at least 10 to 16 times higher than the World Health Organization’s annual guidelines. Even after significant improvements by 2005, the concentrations were still five times higher than what is considered safe. These high levels of pollution have led to 656,000 premature deaths in China each year from ailments caused by indoor and outdoor air pollution, according to World Health Organization estimates from 2007.

“The study is evidence that more stringent air-pollution control measures may be warranted in China,” Gallagher says — because of not just the health effects of pollution, but also the economic effects.

China is taking steps to respond to these health and economic concerns. In January, the nation set a target to limit its carbon intensity (the amount of carbon emitted per unit of gross domestic product) by 17 percent by 2015, compared with 2010 levels.

While the MIT study looked at the benefits of pollution-control measures on health in China, it did not calculate the costs of implementing such policies. That is work the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change’s new China Energy and Climate Project hopes to accomplish.

“We’re just getting started on an exciting program of work that will involve modeling the energy, environmental and economic impacts of climate and air-quality policies in China,” says Valerie Karplus, director of the China Energy and Climate Project. “The current study has provided initial insights and a strong foundation for this research going forward.”

The China Energy and Climate Project will analyze the impact of existing and proposed energy and climate policies in China on technology, energy use, the environment and economic welfare.

By Josh Max

It’s official – we don’t want cars that get 200 or more miles to the gallon, and it’s consumers’ fault, not automakers’.

A new report issued by Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Christopher Knittel says major innovations in miles-to-the-gallon have been stymied by cars that are larger and more powerful than they were 30 years ago.

Between 1980 and 2006, the average gas mileage of vehicles sold in the United States increased by slightly more than 15 percent — a relatively modest improvement, says Knittel. “But during that time, the average weight of those vehicles increased 26 percent, while their horsepower rose 107 percent. All factors being equal, fuel economy actually increased by 60 percent between 1980 and 2006.” If cars had stayed the same weight and size since 1980, says Knittel, we’d all be getting an average of 73 MPG instead of our current average of 27.

“Most of that technological progress has gone into [compensating for] weight and horsepower,” he says, adding that we ought to make drivers cough up for their own pollution.

“When it comes to climate change, leaving the market alone isn’t going to lead to the efficient outcome,” Knittel says. “The right starting point is a gas tax.”

Knittel conducted his study by using data from auto trade journals, manufacturers and data from the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration, which revealed that Americans have chosen to buy larger, less fuel-efficient vehicles over the last 30 years despite far more public awareness of pollution, global warming and other serious environmental issues. In 1980, for example, light trucks accounted for about 20 percent of passenger vehicles sold in America. By 2004, light trucks, including SUVs, accounted for 51 percent of sales.

And despite current national gas prices being higher than they’ve ever been in the history of the internal combustion vehicle - $3.48 per regular gallon - gas prices dropped by 30 percent when adjusted for inflation between 1980 and 2004, Knittel says. The blame, he says, lies with the consumer, not the seller.

“I find little fault with the auto manufacturers, because there has been no incentive to put technologies into overall fuel economy,” Knittel says. “Firms are going to give consumers what they want, and if gas prices are low, consumers are going to want big, fast cars. I think 98 percent of economists would say that we need higher gas taxes.”

By: Richard Harris

Listen to the story.

SOURCE: Keith Srakocic/AP

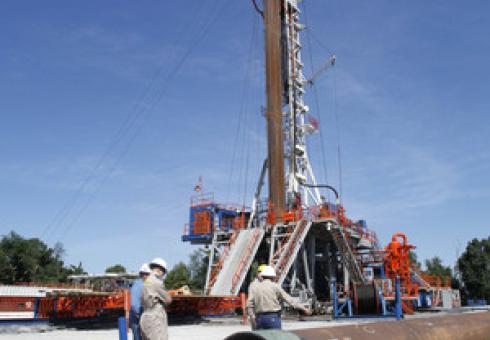

The boom in cheap natural gas in this country is good news for the environment, because relatively clean gas is replacing dirty coal-fired power plants. But in the long run, cheap natural gas could slow the growth of even cleaner sources of energy, such as wind and solar power.

Natural gas has a bad rap in some parts of the country, because the process of fracking is not popular. But many people looking at cheap natural gas from the global perspective see it as a good thing.

Henry Jacoby, an economist at the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research at MIT, says cheap energy will help pump up the economy.

"Overall, this is a great boon to the United States," he says. "It's not a bad thing to have this new and available domestic resource." He says cheap energy can boost the economy, and he notes that natural gas is half as polluting as coal when it's burned for electricity.

"But we have to keep our eye on the ball long-term," Jacoby says. He's concerned about how cheap gas will affect much cleaner sources of energy. Wind and solar power are more expensive than natural gas, and though those prices have been coming down, they're chasing a moving target that has fallen fast: natural gas.

"It makes the prospects for large-scale expansion of those technologies more chancy," Jacoby says.

Natural Gas: 'A Bridge To Nowhere'?

From an environmental perspective, natural gas could help transition our economy from fossil fuels to clean energy. It's often portrayed as a bridge fuel to help us through the transition, because it's so much cleaner than coal and it's abundant. But Jacoby says that bridge could be in trouble if cheap gas kills the incentive to develop renewable industry.

"You'd better be thinking about a landing of the bridge at the other end. If there's no landing at the other end, it's just a bridge to nowhere," he says.

In the short run, at least, the wind industry isn't too worried about this. Denise Bode, who heads the American Wind Energy Association, says low gas prices don't undercut current prices for wind, because those are mostly fixed by 20-year contracts, not market prices.

And even if wind is a bit more expensive than natural gas, she says utilities still want it in their mix. Windmills aren't subject to changing fuel prices, so the cost of production is quite predictable. That's not true for natural gas — there's no guarantee that today's cheap prices will stay as low as some predict.

"It's very difficult to really know how certain that is, so you always want to balance that with something that is certain," Bode says.

Reducing Political Will For Renewables?

What really worries her isn't natural gas — it's politics. Wind could lose a huge tax break at the end of this year. And that would have a much more dramatic effect than low natural gas prices.

"You'll see very low numbers" for new wind installations if the federal production tax credit expires," Bode says. "In fact, I think EIA [the U.S. Energy Information Administration] projects almost zero for 2013."

The solar industry's subsidies run for several more years, so they are not in that bind, at least not yet. But Trevor Houser, an energy analyst at the Rhodium Group, says these tax credits and other incentives like state renewable standards are key if renewables are to grow and mature during the natural-gas glut.

"Long-term renewable deployment in the U.S. is going to depend primarily on policy," Houser says. "Is there enough concern about environmental consequences to put in place incentives for renewable energy?"

That partly depends on how much of a premium people and companies will be willing to pay for cleaner energy. Right now, with natural gas so cheap, that premium is fairly substantial.

"If those prices hang around for another three or four years, then I think you'll definitely see reduced political will for renewable energy deployment, " Houser says. "But we don't expect prices that low to hang around that long, because low prices are in many ways self-correcting."

Gas is so cheap now that companies that produce it are struggling to make a profit. So Houser expects prices to move up. That will help close the price gap between gas and renewable energy.

Even so, there's still a huge way to go before prices and government policies do enough to significantly reduce emissions of the gases that contribute to global warming.