News + Media

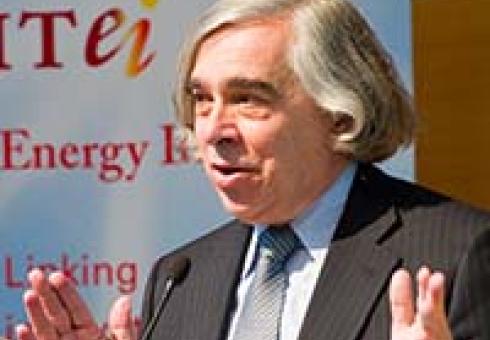

President Barack Obama announced today that he intends to nominate MIT’s Ernest J. Moniz to head the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

President Barack Obama announced today that he intends to nominate MIT’s Ernest J. Moniz to head the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

Moniz is the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Physics and Engineering Systems, as well as the director of the MIT Energy Initiative (MITEI) and the Laboratory for Energy and the Environment. At MIT, Moniz has also served previously as head of the Department of Physics and as director of the Bates Linear Accelerator Center. His principal research contributions have been in theoretical nuclear physics and in energy technology and policy studies. He has been on the MIT faculty since 1973.

"President Obama has made an excellent choice in his selection of Professor Moniz as Energy Secretary,” said MIT President L. Rafael Reif. “His leadership of MITEI has been in the best tradition of the Institute — MIT students and faculty focusing their expertise and creativity on solving major societal challenges, a history of working with industry on high-impact solutions, and a culture of interdisciplinary research.” Reif continued, “We have been fortunate that Professor Moniz has put his enthusiasm, deep understanding of energy, and commitment to a clean energy future to work for MIT and the Energy Initiative — and we are certain he will do the same for the American people."

Moniz is the founding director of MITEI, which was created in 2006 by then–MIT President Susan Hockfield. MITEI is designed to link science, innovation and policy to help transform global energy systems. Under Moniz’s stewardship, MITEI has supported almost 800 research projects at the Institute, has 23 industry and public partners supporting research and analysis, and has engaged 25 percent of the MIT faculty in its projects and programs.

At last count, more than two-thirds of the research projects supported through MITEI have been in renewable energy, energy efficiency, carbon management, and enabling tools such as biotechnology, nanotechnology and advanced modeling. The largest single area of funded research is in solar energy, with more than 100 research projects in this area alone.

Projects supported through MITEI have fostered the development of such innovative technologies as low-cost solar cells that can be printed directly onto paper or other flexible, inexpensive materials; utility-scale liquid batteries that could enable grid integration of intermittent energy sources; transparent solar cells that could be built into display screens or windows; and bioengineered batteries. More than 100 MITEI seed fund projects have served to attract many MIT faculty to energy-related research. Several MITEI-supported projects have led to the formation of startup companies, reflecting the Institute’s long-standing focus on commercializing technology solutions.

In addition, MITEI has a major focus on education. It has awarded 252 graduate fellowships in energy, 104 undergraduate research opportunities and, in 2009, established a new energy minor, which is already one of the largest at the Institute. MITEI also supports a range of student-led research projects to green the MIT campus.

MITEI has furthered a series of influential in-depth studies that provide technically grounded analyses to energy leaders and policymakers; major studies have included the Future of Nuclear Power and of Nuclear Fuel Cycles, Future of Coal, Future of the Electric Grid, and the Future of Natural Gas. MITEI is currently well along on a comprehensive study on the future of solar energy.

"Professor Moniz is well prepared to take on this critically important role,” said Susan Hockfield. “When I called for the establishment of MITEI, I knew that it would require superb leadership. Professor Moniz has provided it, and he has shown a remarkable ability to discern how best to bring groundbreaking research to bear on both immediate and longer-term energy problems. He has brought together industry, government and the academy to address the global challenge of sustainable energy."

Moniz served as undersecretary of energy from 1997 to 2001. In that role, he had oversight responsibility for all of DOE’s science and energy programs and the DOE national laboratory system. He also led a comprehensive review of the nuclear weapons stockpile stewardship program, advanced the science and technology of environmental cleanup, and served as DOE’s special negotiator for Russia initiatives, with a particular focus on the disposal of Russian nuclear materials.

From 1995 to 1997, he served as the associate director for science in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. There, his responsibilities spanned the physical, life, and social and behavioral sciences; science education; and university-government partnerships.

He currently serves on the President’s Council of Advisors for Science and Technology and on the Department of Defense Threat Reduction Advisory Committee. He recently served on the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future.

Moniz received a B.S. in physics from Boston College and a Ph.D. in theoretical physics from Stanford University. He was then a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow at Saclay, France, and at the University of Pennsylvania. He holds honorary doctorates from the University of Athens, the University of Erlangen-Nuremburg and Michigan State University.

Moniz is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Humboldt Foundation, and the American Physical Society, and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. He received the 1998 Seymour Cray HPCC Industry Recognition Award for vision and leadership in advancing scientific simulation and, in 2008, the Grand Cross of the Order of Makarios III for contributions to development of research, technology and education in Cyprus and the wider region.

DOE’s mission is to ensure America’s security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental and nuclear challenges through science and technology. The agency had a budget of more than $29 billion in fiscal year 2012; runs 17 national laboratories, and many other research facilities; and has more than 16,000 federal employees and 90,000 contract employees at the national laboratories and other facilities. DOE is the largest funder of research in the physical sciences.

By Brad Plumer

February 22, 2013

What’s the best way to curtail gasoline consumption? Economists tend to agree on the answer here: Higher gas taxes at the pump are more effective than stricter fuel-economy standards for cars and trucks.

Much more effective, in fact. A new paper from researchers at MIT’s Global Change program finds that higher gas taxes are “at least six to fourteen times” more cost-effective than stricter fuel-economy standards at reducing gasoline consumption.

Why is that? One of the study’s co-authors, Valerie Karplus, offers a basic breakdown here: Fuel-economy standards work slowly, as manufacturers start selling more efficient vehicles, and people retire their older cars and trucks. That turnover takes time. By contrast, a higher gas tax kicks in immediately, giving people incentives to drive less, carpool more, and buy more fuel-efficient vehicles as soon as possible.

A great deal also depends on whether biofuels and other alternative fuels are available. A tax on gasoline makes these alternative fuels more competitive, whereas fuel-economy standards don’t. “We see the steepest jump in economic cost between efficiency standards and the gasoline tax if we assume low-cost biofuels are available,” Karplus said in an MIT press release.

And yet… all this economic research never seems to have any effect on lawmakers. Since 2007, Congress and the Obama administration have moved to increase federal fuel economy standards, now scheduled to rise to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. According to the MIT estimates, this will cost the economy six times as much as simply raising the federal gas tax from its current level of 18.4 cents per gallon to 45 cents per gallon. Yet no one in Congress has even proposed the latter option.

One explanation is that the public just prefers things this way. Higher fuel-economy standards do impose costs, but they’re largely “hidden” costs — in the form of pricier vehicles in the showroom. A higher gas tax, by contrast, is visible every time people fill up at the pump.

In fact, a recent NBER paper by MIT’s Christopher Knittel found that this has been the case for decades. Between 1972 and 1980 the price of oil soared 650 percent. There was endless public debate during this period about how best to reduce reliance on fossil fuels. And, as Knittel discovered, the public consistently preferred price controls and fuel-economy standards over higher gas taxes. That was true no matter how often people were informed that gas taxes were the superior option.

“Given the saliency of rationing and vehicle taxes,” Knittel concluded, “it seems difficult to argue that these alternative polices were adopted because they hide their true costs.” In other words, the public seems to have an (expensive) preference for inefficient regulations over higher taxes to curb gasoline. Economists find it maddening, but it’s hard to change.

Further reading:

–On the other hand, if you want to see a rare economic argument for fuel-economy standards, check out this 2006 paper (pdf) by Christopher Knittel. He found that Americans were becoming less sensitive to fuel prices over time — which strengthened the case for policies like CAFE standards.

THE average price of gasoline in the United States, $3.78 on Thursday, has been steadily climbing for more than a month and is approaching the three previous post-recession peaks, in May 2011 and in April and September of last year.

But if our goal is to get Americans to drive less and use more fuel-efficient vehicles, and to reduce air pollution and the emission of greenhouse gases, gas prices need to be even higher. The current federal gasoline tax, 18.4 cents a gallon, has been essentially stable since 1993; in inflation-adjusted terms, it’s fallen by 40 percent since then.

Politicians of both parties understandably fear that raising the gas tax would enrage voters. It certainly wouldn’t make lives easier for struggling families. But the gasoline tax is a tool of energy and transportation policy, not social policy, like the minimum wage.

Instead of penalizing gasoline use, however, the Obama administration chose a familiar and politically easier path: raising fuel-efficiency standards for cars and light trucks. The White House said last year that the gas savings would be comparable to lowering the price of gasoline by $1 a gallon by 2025. But it will have no effect on the 230 million passenger vehicles now on the road.

Greater efficiency packs less of a psychological punch because consumers pay more only when they buy a new car. In contrast, motorists are reminded regularly of the price at the pump. But the new fuel-efficiency standards are far less efficient than raising gasoline prices.

In a paper published online this week in the journal Energy Economics, I and other scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology estimate that the new standards will cost the economy on the whole — for the same reduction in gas use — at least six times more than a federal gas tax of roughly 45 cents per dollar of gasoline. That is because a gas tax provides immediate, direct incentives for drivers to reduce gasoline use, while the efficiency standards must squeeze the reduction out of new vehicles only. The new standards also encourage more driving, not less.

Other industrialized democracies have accepted much higher gas taxes as a price for roads and bridges and now depend on the revenue. In fact, Germany’s gas tax is 18 times higher than the United States’ (and seven times more if the average state gas tax is included). The federal gasoline tax contributed about $25 billion in revenues in 2009.

Raising the tax has generally succeeded only when it was sold as a way to lower the deficit or improve infrastructure or both. A 1-cent federal gasoline tax was created in 1932, during the Depression. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan raised the tax to 9 cents from 4 cents, calling it a “user fee” to finance transportation improvements. The tax rose again, to 14.1 cents in 1990, and to 18.4 cents in 1993, as part of deficit-reduction deals under President George Bush and President Bill Clinton.

A higher gas tax would help fix crumbling highways while also generating money that could help offset the impact on low- and middle-income families. Increasing the tax, as part of a bipartisan budget deal, with a clear explanation to the public of its role in lowering oil imports and improving our air and highways, could be among the most important energy decisions we make.

Valerie J. Karplus is a research scientist in the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change at M.I.T.

Read more about the study here.

Related: Carbon Tax a 'Win-Win-Win' for America's Future

MIT researchers find vehicle efficiency standards are at least six times more costly than a tax on fuel.

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT: Valerie Karplus makes her case in an op-ed in the NY Times here.

Vehicle efficiency standards have long been considered vital to cutting the United States’ oil imports. Strengthened last year with the added hope of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the standards have been advanced as a way to cut vehicle emissions in half and save consumers more than $1.7 trillion at the pump. But researchers at MIT find that, compared to a gasoline tax, vehicle efficiency standards come with a steep price tag.

“Tighter vehicle efficiency standards through 2025 were seen as an important political victory. However, the standards are a clear example of how economic considerations are at odds with political considerations,” says Valerie Karplus, the lead author of the study and a researcher with the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change. “If policymakers had made their decision based on the broader costs to the economy, they would have gone with the option that was least expensive – and that’s the gasoline tax.”

The study, published this week in the March edition of the journal Energy Economics, compares vehicle efficiency standards to a tax on fuel as a tool for reducing gasoline use in vehicles. The researchers found that regardless of how quickly vehicle efficiency standards are introduced, and whether or not biofuels are available, the efficiency standards are at least six times more expensive than a gasoline tax as a way to achieve a cumulative reduction in gasoline use of 20 percent through 2050. That’s because a gasoline tax provides immediate, direct incentives for reducing gasoline use, both by driving less and investing in more efficient vehicles. Perhaps a central reason why politics has trumped economic reasoning, Karplus says, is the visibility of the costs.

“A tax on gasoline has proven to be a nonstarter for many decades in the U.S., and I think one of the reasons is that it would be very visible to consumers every time they go to fill up their cars,” Karplus says. “With a vehicle efficiency standard, your costs won't increase unless you buy a new car, and even better than that, policymakers will tell you you’re actually saving money. As my colleague likes to say, you may see more money in your front pocket, but you’re actually financing the policy out of your back pocket through your tax dollars and at the point of your vehicle purchase.”

Along with being more costly, Karplus and her colleagues find that it takes longer to reduce emissions under the vehicle efficiency standards. That’s because, with more efficient vehicles, it costs less to drive, so Americans tend to drive more. Meanwhile, the standards have no direct impact on fuel used in the 230 million vehicles currently on the road. Karplus also points out that how quickly the standards are phased in can make a big difference. The sooner efficient vehicles are introduced into the fleet, the sooner fuel use decreases and the larger the cumulative decrease would be over the period considered, but the timing of the standards will also affect their cost.

The researchers also find that the effectiveness of the efficiency standards depends in part on the availability of other clean-energy technologies, such as biofuels, that offer an alternative to gasoline.

“We see the steepest jump in economic cost between efficiency standards and the gasoline tax if we assume low-cost biofuels are available,” Karplus says. “In this case, if biofuels are available, a lower gasoline tax is needed to displace the same level of fuel use over the 2010 to 2050 time frame, as biofuels provide a cost-effective way to displace gasoline above a certain price point. As a result, a lower gas tax is needed to achieve the 20 percent cumulative reduction.”

To project the impact of vehicle efficiency standards, Karplus and her colleagues improved the MIT Emissions Predictions and Policy Analysis Model that is used to help understand how different scenarios to constrain energy affect our environment and economy. For example, they represent in the model alternatives to the internal combustion engine based on the expected availability and cost of alternative fuels and technologies, as well as the dynamics of sales and scrappage that affect the composition of the vehicle fleet. Their improvements to the model were recently published in the January 2013 issue of the journal Economic Modelling.

Nature: Natural hazards: New York vs the sea

By: Jeff Tollefson

February 13, 2013

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, scientists and officials are trying to protect the largest US city from future floods.

Joe Leader's heart sank as he descended into the South Ferry subway station at the southern tip of Manhattan in New York. It was 8 p.m. on 29 October, and Hurricane Sandy had just made landfall some 150 kilometres south in New Jersey. As chief maintenance officer for the New York city subway system, Leader was out on patrol. He had hoped that the South Ferry station would be a refuge from the storm. Instead, he was greeted by wailing smoke alarms and the roar of gushing water. Three-quarters of the way down the final set of stairs, he pointed his flashlight into the darkness: seawater had already submerged the train platform and was rising a step every minute or two.

“Up until that moment,” Leader recalls, standing on the very same steps, “I thought we were going to be fine.”

Opened in 2009 at a cost of US$545 million, the South Ferry station is now a mess of peeling paint, broken escalators and corroded electrical equipment. Much of Manhattan has returned to normal, but this station, just blocks from one of the world's main financial hubs, could be out of service for 2–3 years. It is just one remnant of a coastal catastrophe wrought by the largest storm in New York's recorded history.

Sandy represents the most significant test yet of the city's claim to be an international leader on the climate front. Working with scientists over the past decade, New York has sought to gird itself against extreme weather and swelling seas and to curb emissions of greenhouse gases — a long-term planning process that few other cities have attempted. But Sandy laid bare the city's vulnerabilities, killing 43 people, leaving thousands homeless, causing an estimated $19 billion in public and private losses and paralysing the financial district. The New York Stock Exchange closed for the first time since 1888, when it was shut down by a massive blizzard.

As the humbled city begins to rebuild, scientists and engineers are trying to assess what happened during Sandy and what problems New York is likely to face in a warmer future. But in a dilemma that echoes wider debates about climate change, there is no consensus about the magnitude of the potential threats — and no agreement about how much the city should spend on coastal defences to reduce them.

On 6 December, during his first major public address after the storm, New York mayor Michael Bloomberg promised to reinvest wisely and to pursue long-term sustainability. But he warned: “We have to live in the real world and make tough decisions based on the costs and benefits.” And he noted that climate change poses threats not just from flooding but also from drought and heat waves. The city must be mindful, he said, “not to fight the last war and miss the new one ahead”.

Calculated risks

In the immediate aftermath of Sandy, lower Manhattan looked like a war zone. Each night, streams of refugees wielding flashlights wandered north out of the blackout zone, where flood waters had knocked out an electrical substation.

The storm devastated several other parts of the city as well. In Staten Island, pounding waves destroyed hundreds of homes, and one neighbourhood in Queens burned to ashes after water sparked an electrical fire. Power outages lasted for more than two weeks in parts of the city. Chastened by the flooding and acutely aware that Hurricane Irene, in 2011, was a near miss, the city is now wondering what comes next.

“Is there a new normal?” asks John Gilbert, chief operating officer of Rudin Management, which manages several office buildings in downtown New York. “And if so, what is it?” Gilbert says that the company is already taking action. At one of its buildings, which took on some 19 million litres of water, the company is moving electrical systems to the second floor. “You have to think that as it has happened, it could happen again,” he says. “And it could be worse.”

At Battery Park, near the South Ferry station, the storm surge from Sandy rose 2.75 metres above the mean high-water level — the highest since gauges were installed there in 1923. In a study published last week in Risk Analysis, researchers working with data from simulated storms concluded that a surge of that magnitude would be expected to hit Battery Park about once every 500 years in the current climate (J. C. J. H. Aerts et al. Risk Anal. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/risa.12008; 2013).

But the study authors and other scientists say that the real risks may be higher. The study used flooding at Battery Park as a measure of hurricane severity, yet it also showed that some storms could cause less damage there and still hammer the city elsewhere. Factoring in those storms could drive up the probability estimates of major hurricane damage to New York.

The 1-in-500 estimate also does not take into account the unusual nature of Sandy. Dubbed a Frankenstorm, Sandy was a marriage of a tropical cyclone and a powerful winter snowstorm, and it veered into the New Jersey coast along with the high tide of a full Moon. “It was a hybrid storm,” says Kerry Emanuel, a hurricane researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge and one of the study's co-authors. “We need to understand how to assess the risks from hybrid events, and I'm not convinced that we do.”

The risks will only increase as the world warms. The New York City Panel on Climate Change's 2010 assessment suggests that local sea level could rise by 0.3–1.4 metres by 2080. Last year, Emanuel and his colleagues found that floods that occur once every 100 years in the current climate could happen every 3–20 years by the end of this century if sea level rises by 1 metre. What is classified as a '500-year' event today could come every 25–240 years (N. Lin et al. Nature Clim. Change 2, 462–467; 2012).

For city planners, the challenge is to rebuild and protect the city in the face of scientific uncertainty. A few scientists have said for more than a decade that the city should armour New York's harbour with a storm-surge barrier similar to the Thames barrier in London. In Sandy's wake, that idea has gained renewed interest, and a New York state panel last month called for a formal assessment of it.

Bridges and barriers

Malcolm Bowman, who heads the storm-surge modelling laboratory at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, has spearheaded the drive for barriers. He imagines a structure roughly 8 kilometres wide and 6 metres high at the entrance to the harbour, and a second barrier where the East River drains into the Long Island Sound. The state panel's cost estimates for such a system range from $7 billion to $29 billion, depending on the design. The harbour barrier could also serve as a bridge for trains and vehicles to the city's airports, suggests Bowman. “My viewpoint is not that we should start pouring concrete next week, but I do think we need to do the studies,” he says. But whether Sandy will push the city to build major defences, Bowman says, “I don't know.”

Disasters have spurred costly action in the past. The 1888 blizzard helped to drive New York to put its elevated commuter trains underground. And in 2012, the US Army Corps of Engineers completed a $1.1-billion surge barrier in New Orleans, Louisiana, as part of a $14.6-billion effort to protect the city after it was battered by hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005. But the New York metropolitan area is bigger and more complex than New Orleans, and protecting it will require a multi-pronged approach. Several hundred thousand city residents live along more than 800 kilometres of coastline, and a barrier would not protect much of coastal Long Island, where Sandy wrought considerable damage. Moreover, the barrier would work only against occasional storm surges. It would not hold back the slowly rising sea or protect against flooding caused by rain.

“A storm-surge barrier may be appropriate, but it's never one thing that is going to protect you,” says Adam Freed, a programme director at the Nature Conservancy in New York, who until late last year was deputy director of the city's office of long-term planning and sustainability. “It's going to be a holistic approach, including a lot of unsexy things like elevating electrical equipment out of the basement and providing more back-up generators.”

As part of that holistic effort, officials are exploring options for expanding the remaining bits of wetlands that once surrounded the city and buffered it from storms. In his address, Bloomberg called wetlands “perhaps the best natural barriers against storms that we have”.

But most of the city's wetlands have become prime real estate in recent decades, and Sandy made clear the consequences of developing those areas, says Marit Larson, director of wetlands and riparian restoration for the New York parks department.

A few weeks after the storm, Larson parks her car near the beach on Staten Island and looks out at a field of Phragmites australis, a common marsh reed. The field is part of Staten Island's 'Bluebelt' programme, initiated in the late 1980s to promote wetlands and better manage storm-water runoff. But the patch of wetlands here is smaller than a football pitch, and Sandy's surge rolled over it, damaging the nearby row houses. “If you look at the historical maps,” says Larson, “everything that used to be a wetland got wet.”

New York is now moving to strengthen its network of existing wetlands, which cover some 2,300–4,000 hectares. The mayor's budget plan for 2013–17 includes more than $200 million to restore wetlands as part of an effort to protect and redesign coastal developments.

Sandy also showed how proper construction can help to reduce risks from future storms. In one Staten Island neighbourhood, a battered roof rests on the ground, marking the spot where an ageing bungalow once stood. Next door, a newer house still stands, with no apparent damage apart from a flooded garage — sturdy proof of the value of modern building codes. In New York, newer buildings constructed in 100-year-flood zones, which are defined by the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), cannot have any living spaces or major equipment, such as heating units, below the projected flood level (see 'Danger zone').

The city's zoning provisions could not protect against a storm like Sandy: officials estimate that two-thirds of the homes damaged by the storm were outside the 100-year-flood area. But scientists say that the FEMA flood maps were out of date, so even century-scale storms could cause damage well beyond the designated areas. Last month, FEMA began releasing new flood maps for the New York region that substantially expand this zone.

In their latest study, Emanuel and his colleagues estimate the average annual flood risk for New York as only $59 million to $129 million in direct damages. But costs could reach $5 billion for 100-year storms and $11 billion for 500-year storms. These figures do not include lost productivity or damage to major infrastructure, such as subways.

Bowman and other researchers argue that the city should commit to protecting all areas to a 500-year-flood standard, but not all the solutions are physical. A growing chorus of academics and government officials stress that the city must also bolster its response capacity and shore up the basic social services that help people to rebuild and recover.

Most importantly, the city and surrounding region need to develop a comprehensive strategy for defending the coastline, says Jeroen Aerts, a co-author of the Risk Analysis assessment who studies coastal-risk management at VU University in Amsterdam. Aerts is working with New York officials to analyse proposals for the barrier system and a suite of changes in urban planning, zoning and insurance. “You need a master plan,” he says.

“Ultimately, we all have to move together to higher ground.”

Seth Pinsky is working towards that goal. As president of the New York City Economic Development Corporation, he was tapped by Bloomberg to develop a comprehensive recovery plan that will make neighbourhoods and infrastructure safer. He points out that some newer waterfront parks and residential developments along the coast fared well during the storm. For example, at Arverne by the Sea, a housing complex in Queens, Pinsky says that units survived because they are elevated and set back from the water, with some protection from dunes. The buildings suffered little damage compared with surrounding areas.

Intelligent design

The cost of strengthening the city will be astronomical. In January, Congress approved some $60 billion to fund Sandy recovery efforts, with around $33 billion for longer-term investments, including infrastructure repair and construction by the Army Corps of Engineers. Pinsky says that he does not yet know how much of that money will go to New York, but he is sure it will not be enough. The city will define its budget in June, after his group has made its official recommendations. The rebuilding endeavour will probably necessitate a “creative” mix of public and private financing, he says. “It will probably require calling on a combination of almost every tactic that has been tried around the world.”

Even as he calls for more intelligent development, Pinsky says that New York is unlikely to take a drastic approach to dealing with storm surge and sea-level rise. “Retreating from the coastline of New York city both will not be necessary and is not really possible,” he says.

Given the sheer scale of development along the coast, it is hard to argue with Pinsky's assessment. But many climate scientists fear that bolstering coastal developments only delays the eventual reckoning and increases the likelihood of future disasters. The oceans will rise well into the future, they say, so cities will eventually be forced to accommodate the water.

“I don't see anything yet that looks towards long-term solutions,” says Klaus Jacob, a geoscientist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, New York. But Jacob admits that he is as guilty as anyone. In 2003, he and his wife bought a home in a low-lying area on the Hudson River in Piermont, New York. Although it went against his professional principles, he agreed to the purchase with the assumption that he could elevate the house. But height-restriction laws prevented him from doing so, and Sandy flooded the house. The couple are now rebuilding.

“In a way, I think I was in denial about the risk,” Jacob says. He hopes that a new application to raise the house will be approved, but he still fears that the neighbourhood will not survive sea-level rise at the end of the century. New Yorkers and coastal residents everywhere would be wise to learn that lesson. “Ultimately,” Jacob says, “we all have to move together to higher ground.”

Nature 494, 162–164 (14 February 2013) doi:10.1038/494162a

Susan Solomon has won both the Vetlesen Prize and a 2012 BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award.

The Vetlesen Prize is given “for scientific achievement resulting in a clearer understanding of the Earth, its history, or its relations to the universe” and is designed to recognize sweeping achievements on par with the Nobel. The Prize was established in 1959 and is given every several years by a selection committee appointed by the president of Columbia University. The most recent award was in 2008 to geologist Walter Alvarez. Previous winners include climate scientists Sir Nicholas Shackleton and Wallace Broecker, marine geologist Walter Pitman, seismologist Lynn Sykes, and founding director of Lamont Maurice “Doc” Ewing.

Soloman is being recognized for her work in identifying the cause of the Antarctic ozone hole. This research helped bring about a global ban on manmade ozone-depleting chemicals. She shares the award with French climate scientist Jean Jouzel who is being recognized for his work extracting the longest-yet climate record from polar ice cores. The pair will receive the award and accompanying medal at Columbia's Low Library on Thursday, February 21st.

The BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Awards recognize, among other things, outstanding contributions that advance understanding or deliver material progress with regard to climate change, one of the key challenges of the global society of the 21st century.

The award citation states that Solomon "has contributed, through her research and leadership, to the safeguarding of our planet." Solomon's work over 30 years has succeeded in establishing and drawing together links between three key climate change variables: human activity, a profound and comprehensive understanding of the behavior of atmospheric gases, and the alteration of climate patterns globally.

IN THE NEWS: Changing with the climate

MIT News

January 25, 2013

MIT researchers, Massachusetts officials highlight strategies to adapt to climate change.

Just days after President Obama called for action on climate change in his second inaugural address, members of Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick’s administration joined energy and environment researchers at MIT to discuss strategies for adapting to climate change. The panel discussion on Jan. 23 fostered a continued partnership between MIT and the Commonwealth to advance energy and environment innovation. More....

IN THE NEWS: Reporter's Notebook: An inside tour of the MassDOT

The Tech

January 30, 2013

MIT students frequently use the T and other MassDOT transit systems; since 2010, our IDs even come with a built-in Charlie Card chip. But most students are unfamiliar with the inner workings of the transit system.

Ethan Feuer, Student Activities Coordinator for the MIT Energy Initiative, organized the tour for twenty five students in order to learn more about large infrastructures and emergency preparedness in cities. More....

IN THE NEWS: Climate Research Showcase

MITEI and MIT Joint Program

February 11, 2013

MIT students, researchers help Massachusetts address a post-Sandy world.

MIT students and researchers brought their latest ideas and findings to the table at an event on January 29. The interdisciplinary group of young researchers presented to officials from the Commonwealth’s Executive Office of Energy and the Environment, in hopes that the state would be able to leverage the information for future planning and implementation. More...

Last month, the United Nations Environment Programme agreed on the first major environmental treaty in over a decade. Its focus was reducing mercury pollution. There to participate in the events were ten MIT students and their instructor Noelle Selin, a researcher with the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change and an assistant professor of atmospheric chemistry and engineering systems.

To share their experiences and lessons learned from witnessing international environmental policy-making in action, Selin and the students hosted a panel discussion on Wednesday, February 6.

Selin kicked off the event by describing the problem of mercury in our environment and why an international treaty was essential to curbing the environmental and public health effects. She explained that mercury levels in the Earth have increased greatly due to the burning of fossil fuels, cement production, and more. Mercury then rains down into oceans, where it contaminates fish as toxic methylmercury.

"The health risks to consumers of fish include neurological effects, particularly in the offspring of exposed pregnant women," Selin explained. “Over 300,000 newborns in the U.S. each year are at risk of learning disabilities due to their elevated mercury exposure."

Mercury is an element that cycles in the environment, meaning that once it’s released into the atmosphere it can take decades to centuries for mercury to make its way back to ocean sediments.

“This becomes a global issue, this becomes a long term issue, and thus an issue for international cooperation,” Selin said.

There were five student teams on the trip that covered topics including: governing institutions, products and processes, emissions, waste/trade/mining, and finance. A member from each team presented on their issue at the panel and shared their thoughts and observations on the international negotiation process.

Philip Wolfe, a PhD candidate in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, discussed the institutions and policy process of the negotiations. He explained that the treaty has to work on two levels: globally and domestically.

“Individual countries engage in regional, domestic, or bilateral agreements and they’ll only really sign on to a global convention if it also meets their own domestic goals,” Wolfe said.

The treaty, if nations decide to sign it, would require tightly controlling emissions – a major area of discussion during the negotiations.

Leah Stokes, PhD candidate in Environmental Policy and Planning, discussed the challenges with regulating emissions from the burning of fossil fuels and artisanal small-scale gold mining. She explained that when individuals want to mine gold and don’t have any equipment they use mercury because it binds with gold. When burned together, the mercury burns first, leaving gold behind. This process is estimated by the United Nations to be the largest global contributor of mercury emissions.

“We also come into contact with mercury through a lot of the products we use,” explained Ellen Czaika, a PhD candidate in Engineering Systems Division.

Examples of products with mercury that will be phased out under the treaty include some types of compact fluorescent light blubs, dental fillings, pesticides, thermometers, and batteries. There were important discussions at the conference about weighing the benefits of some of these products versus their mercury risks, Czaika said.

Mercury mining is another source of concern, and a major piece of the treaty. Danya Rumore, a PhD student in Environmental Policy and Planning, explained that this was expected to be a big area of contention, but an agreement was reached that gave time for a ban to come into effect over a 15-year period.

Julie van der Hoop, a PhD student in the MIT/Woods Hole Oceanographic Joint Program, followed financial and technical assistance issues at the negotiations. She discussed how the strength and effectiveness of the treaty will be shown through the technology transfer programs, a new funding mechanism for developing nations, and implementation plans.

Ultimately, she said, “We’re looking for a treaty to be effective…If you make a treaty and it’s not effective then what’s the point?”

Many of the panelists said that the treaty has relatively weak requirements, but that this is still a historic and impactful international environmental treaty. Selin recognized that it had to be an agreement that all 140 countries would be able to sign on to and that any limits on mercury will have long-term impacts because of the nature of the mercury cycle.

“This isn’t a thing that ends today,” Stokes, of Environmental Policy and Planning, said. “This is just something that keeps going and going and going. Even though we have a treaty—really, we’re going to decide everything [about implementation] at the next meeting.”

The students attended the conference as part of a National Science Foundation grant, with the idea being to train a cohort of graduate students for science policy leadership through a semester-long course and an intensive policy engagement exercise. The group had UN observer status and was able to observe all of the negotiations, breakout sessions, and meetings. The students also presented their latest scientific information about mercury through a poster presentation, and shared their experiences and observations through a blog and twitter feed.

As Massachusetts and communities throughout the country face the realities of a world where severe weather events like Super Storm Sandy could become more common, smart adaptation strategies are needed. MIT students and researchers brought their latest ideas and findings to the table at an event on January 29. The interdisciplinary group of young researchers presented to officials from the Commonwealth’s Executive Office of Energy and the Environment, in hopes that the state would be able to leverage the information for future planning and implementation.

Going forward we will need to be thinking out-off-the-box, creatively for future planning ” Massachusetts Energy Undersecretary Barbara Kates-Garnick said at the event. “So much of what you’re doing is totally relevant to what we’re working on…I’m sure that we will be back in touch."

The student showcase was part of a series of events the MIT Energy Initiative organized during the MIT independent activities period to highlight what is being done – and what needs to be done – to face the realities of a post-Sandy world.

Included in the series of events was a panel discussion on January 23 featuring Massachusetts’ officials and MIT Professors Kerry Emanuel and Michael Greenstone. Learn more about the event, and watch the video of the panel, here.

The MIT Energy Initiative also organized a tour of the MBTA’s tunnels. Participants learned what the MBTA is doing to modernize and adapt to change. Read the MIT Tech story here.

Research aimed at predicting future climate activity has primarily focused on large and complex numerical models. While this approach has provided some quantitative estimates of climate change, those predictions can vary greatly from one model to the next and produce doubts in the projected outcome.

In this Faculty Forum Online broadcast Professor Kerry Emanuel '76, PhD '78 discussed a new approach to climate science that emphasizes basic understanding over black box simulation. On Tuesday, Feb. 5, 2013, Emanuel presented an overview of his climate research and took questions from the worldwide MIT community via video chat. Watch the video and visit the Slice of MIT blog to continue the conversation in the comments.

About Kerry Emanuel

A Cecil and Ida Green Professor in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Emanuel is a cofounder of the Lorenz Center, an MIT think tank devoted to understanding climate activity. He is the author of What We Know about Climate Change, which The New York Times called "the single best thing written about climate change for a general audience."

In 2006, Emanuel was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. He received his bachelor's degree in earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences from MIT in 1976 and his doctorate in meteorology from MIT in 1978.