News + Media

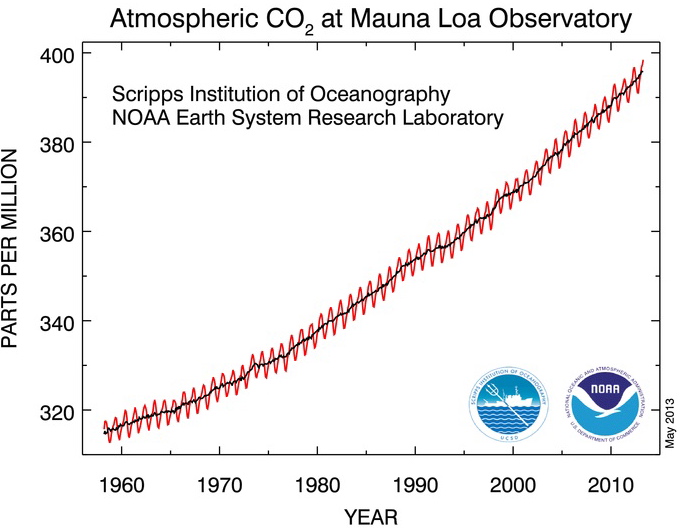

The Keeling Curve record from the NOAA-operated Mauna Loa Observatory shows that the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration hovers around 400 ppm, a level not seen in more than 3 million years when sea levels were as much as 80 feet higher than today. Virtually every media outlet reported the passage of this climate milestone, but we suspect there’s more to the story. Oceans at MIT’s Genevieve Wanucha interviewed Ron Prinn, Professor of Atmospheric Science in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. Prinn is the Director of MIT’s Center for Global Change Science (CGCS) and Co-Director of MIT’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change (JPSPGC).

Prinn leads the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE), an international project that continually measures the rates of change of the air concentrations of 50 trace gases involved in the greenhouse effect. He also works with the Integrated Global System Model, which couples economics, climate physics and chemistry, and land and ocean ecosystems, to estimate uncertainty in climate predictions and analyze proposed climate policies.

What is so significant about this 400-ppm reading?

This isn’t the first time that the reading of 400 parts per million (ppm) of atmospheric CO2 was obtained. It was recorded at a NOAA’s observatory station in Barrow, Alaska, in May 2012. But the recent 400-ppm reading at Mauna Loa, Hawaii got into the news because that station produced the famous “Keeling Curve,” which is the longest continuous record of CO2 in the world, going back to 1958.

‘400’ is just a round number. It’s more of a symbol than a true threshold of climate doom. The real issue is that CO2 keeps going up and up at about 2.1 ppm a year. Even though there was a global recession in which emissions were lower in most fully-developed countries, China, and to lesser extent India and Indonesia, blew right through and continued to increase their emissions.

Has anything gone unappreciated in the news coverage of this event?

Yes. What’s not appreciated is that there are a whole lot of other greenhouse gases (GHGs) that have fundamentally changed the composition of our atmosphere since pre-industrial times: methane, nitrous oxide, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), and hydrofluorocarbons. The screen of your laptop is probably manufactured in Taiwan, Japan, and Eastern China by a process that releases nitrogen trifluoride—release of 1 ton of nitrogen trifluoride is equivalent to 16,800 tons of CO2. But there is a fix to that—the contaminated air in the factory could be incinerated to destroy the nitrogen trifluoride before it’s released into the environment.

Many of these other gases are increasing percentage-wise faster than CO2 . In the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE), we continuously measure over 40 of these other GHGs in real time over the globe. If you convert these other GHGs into their equivalent amounts of CO2 that will have the same effect on climate, and add them to the NOAA measurements of CO2, you find that we are actually at 478 ppm of CO2 equivalents right now. In fact, we passed the 400 ppm back in about 1985. So, 478 not 400 is the real number to watch. That’s the number people should be talking about when it comes to climate change.

What has Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) revealed about this greenhouse gas problem?

The non-CO2 GHGs are very powerful. One example is sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), which used to be in Nike shoes, and is now most widely used in the step-down transformers in long-distance electrical power grids. But SF6 leaks a lot, with 1 ton equivalent to 22,800 tons of CO2, and it’s increasing in our measurements. Another example is methane. We have been measuring methane for almost 30 years now, and it actually didn’t increase for almost 8 years from 1998 onwards, but we discovered in our network that it began to increase again in 2006. We published this finding in 2008, and ever since, methane has been rising at a rapid rate. Nitrous oxide, the third most important GHG, has been going up almost linearly since we started measuring it in 1978.

The worrisome thing is that almost all of these gases keep rising and, per ton, they are very powerful drivers of warming. Many of these GHGs have lifetimes of hundreds to thousands to tens of thousands of years, so they are essentially in our atmosphere forever. There is almost nothing practical we can do to vacuum these gases out again.

Is it possible to decrease the atmospheric CO2?

One well-understood method of removing CO2 from the atmosphere is carbon sequestration, in which you remove the CO2 from the biomass burnt in an electrical utility, and then bury it in subsurface saline aquifers or in the deep ocean. There are people here at MIT, Rob van der Hilst and Brad Hager and others, who study the question of just how permanent is this deep burial on land.

Carbon sequestration can also lower CO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants. It looks like the Department of Energy will reactivate a couple of these projects in Wisconsin and Texas to better understand this technology, with the goal of lowering the emissions from power plants to say 10% or less of what they were.

At the end of the day, the smart thing would be not to resort to vacuuming CO2 out of the atmosphere and putting it down deep underground. It would be better to develop new and affordable zero- or very low-emission energy technologies such as biofuels, nuclear, solar and wind.

Will switching to ‘fracked’ natural gas reduce warming?

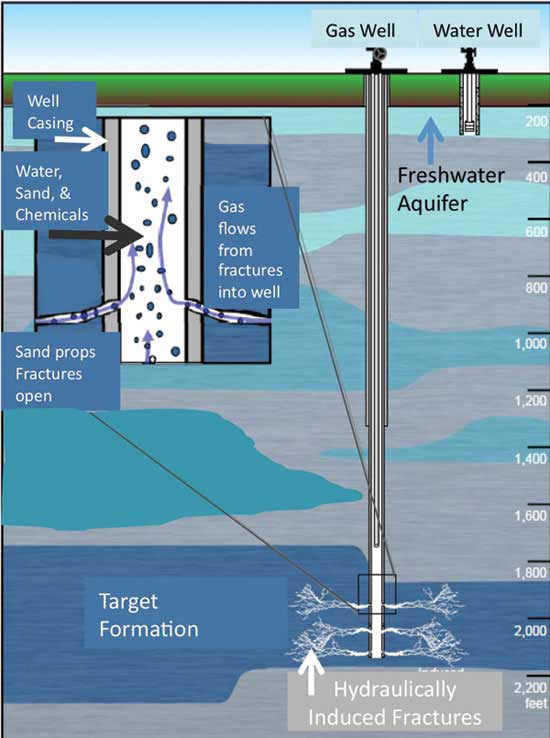

We have run our Integrated Global System Model presuming that hydraulically fractured gas from shale deposits in the US and elsewhere around the world could begin to be used at large scale. We’ve looked at the question of if we did convert all oil usage to fracked gas usage over the next 20-30 years, would it lower the rate of warming? And the answer is yes, because you get about twice as much energy per ton of CO2 emitted from burning methane as you get from coal.

There are some serious issues about the water used to pump down and split the shale. In the fracking process, trace chemicals are added into the water to make it slippery so the water can force itself in between the layers of shale. The problem is, shale is filled with mucky stuff such as salts and heavy organics, which all ends up in the frack water and comes back up to the surface. So what do you do with that very polluted water? Then there is the concern that the water could travel horizontally and vertically through the shale layers and end up in ground water. And that’s an environmental issue that has to be addressed.

However, chemical companies are already investing in technologies that can take the frack water that’s pumped back out and literally clean out the hydrocarbons and re-use it again for fracking. So, there is an answer to the frack water problem, but there must be a strong push to make sure fracking is environmentally sound.

We did find that if you increase the use of fracked gas and didn’t repair the existing natural gas pipelines, they could leak several percent of the transferred volume because it’s old city and intercity infrastructure. It’s leaking now in all major pipeline systems in the US and Europe, which is a problem because the leaked methane is a much more powerful GHG per ton than CO2. So, repairing or replacing old gas pipelines will be a big requirement.

Addressing all these environmental concerns will add somewhat to the cost of energy. But most who study the climate issue in detail and in depth understand that the damages that are going to result from continued warming will far exceed the cost of any policy that we put together to lower GHG emissions. Yet, as you know, the politics of climate in Washington is impossible right now because a minority of senators can block any legislation. It doesn’t look like anything will happen soon on a national emissions reduction policy. Politics trumps science on these issues. But the EPA has the power to treat CO2 as an air pollutant so maybe that’s what will happen near term.

The bottom line is if we switched from using oil and coal globally to running everything on shale gas, there probably is enough gas there. But with this alone, you would still get about a 3.5 C warming by 2100. With no policy at all, our model estimates a 5-degree or higher warming. So replacing coal and oil with fracked gas is a sensible pathway for the US to go over the next few decades, with the additional advantage of gaining more energy independence. But it won’t remove the global warming threat beyond that.

What are the implications of the 478-ppm measurement to human life?

According to the paleoclimatological ice core record, if our planet warms more than 2 C globally (4 C at the poles), we are in trouble. That’s about 6 meters or 20 feet of sea level rise. Most of the world’s valuable infrastructure and high populations are along the coasts. So, the damage and cost of sea level rise alone is potentially very high. Other risky phenomena we face are shifting rainfall patterns that may move the locations of arable farmland out of the US and into Canada. Mexico could grow drier and drier, and there’s concern in the Department of Defense about potential challenges to the security at the southern US border. Other similarly vulnerable areas around the world could face desperate large-scale migrations of people seeking to find places to grow food.

These damages are likely to exceed significantly the costs associated with an efficient and fair GHG policy such as an emission tax whose revenues are used to offset income taxes.

June 6, 2013

Vicki Ekstrom, MIT Energy

The cost and performance of future energy technologies will largely determine to what degree nations are able to reduce the effects of climate change. In a paper released today in Environmental Science & Technology, MIT researchers demonstrate a new approach to help engineers, policymakers and investors think ahead about the types of technologies needed to meet climate goals.

“To reach climate goals, it is important to determine aspirational performance targets for energy technologies currently in development,” says Jessika Trancik, the lead author of the study and an assistant professor of engineering systems. “These targets can guide efforts and hopefully accelerate technological improvement.”

Trancik says that existing climate change mitigation models aren’t suited to provide this information, noting, “This research fills a gap by focusing on technology performance as a mitigation lever and providing a way to compare the dynamic performance of individual energy technologies to climate goals. This provides meaningful targets for engineers in the lab, as well as policymakers looking to create low-carbon policies and investors who need to know where their money can best be spent.”

The model compares the carbon intensity and costs of technologies to emission reduction goals, and maps the position of the technologies on a cost and carbon trade-off curve to evaluate how that position changes over time.

According to Nathan E. Hultman, director of Environmental and Energy Policy Programs at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy, this approach “provides an interesting and useful alternate method of thinking about both the outcomes and the feasibility of a global transition to a low-carbon energy system.” Hultman, who is also a fellow at the Brookings Institution, was not associated with the study.

How do technologies measure up?

According to Trancik, the cost and carbon trade-off curve can be applied to any region and any sector over any period of time to evaluate energy technologies against climate goals. Along with her co-author, MIT master’s student Daniel Cross-Call, she models the period from 2030 to 2050 and specifically studies the U.S. and China’s electricity sectors.

The researchers find that while major demand-side improvements in energy efficiency will buy some time, the U.S. will need to transition at least 70 percent of its energy to carbon-free technologies by 2050 – even if energy demand is low and the emissions reduction target is high.

Demand-side changes buy more time in China. Efficiency, combined with less stringent emissions allocations, allows for one to two more decades of time to transition to carbon-free technologies. During this time, technologies are expected to improve.

This technology focused perspective, Trancik says, “may help developed and developing countries move past the current impasse in climate negotiations.”

While reaching climate goals is a seemingly formidable task, Trancik says that considering changes to technology performance over time is important. When comparing historical changes in technologies to the future changes needed to meet climate targets, the results paint an optimistic picture.

“Past changes in the cost and carbon curve are comparable to the future changes required to reach carbon intensity targets,” Trancik says. “Along both the cost and carbon axes there is a technology that has changed in the past as much as, or more than, the change needed in the future to reach the carbon intensity and associated cost targets. This is good news.”

The research was partially funded by the MIT Energy Initiative.

Last week, the new U.S. secretary of energy, Ernest Moniz, pledged to continue his predecessor’s work in making the Department of Energy a “center of innovation,” while also highlighting projects he thought deserved more attention. Near the top of his list is a renewed emphasis on carbon dioxide capture and storage (CCS), a technology that could prove vital to combating climate change, but is developing far too slowly, according to the International Energy Agency.

May 30, 2013

In the past decade, the massive expansion of China’s production and export of silicon photovoltaic (PV) cells and panels has cratered the price of those items globally, creating tension between China and the United States, and, more recently, China and the European Union. In a new study (see PDF), MIT researchers explain why these tensions could harm the broader solar industry and have spiraling effects for China-U.S. trade relations.

“China and the U.S., and China and the E.U., are in the midst of a blame game as the solar industry is on the brink of collapse — and the tensions could infect technology and commercial development globally,” says John Deutch, the lead author of the study and Institute Professor at MIT. “All the players should understand that the PV industry is globally linked, and jobs and profits are available for those who manufacture and for those who innovate. Given the complex but productive relationships, nations need to find a way to better work together rather than flirt with protectionist measures.”

Over the last decade, manufacturing of PV cells and panels expanded in China, boosting supply globally. The flood of solar panels, combined with a slipping subsidized demand for solar energy (especially in Europe), lowered the global market price to unsustainable levels, the study shows. Between 2009 and 2012, the price of crystalline silicon panels decreased from more than $2.50 per watt to less than $1 per watt, as China supplied 30 to 50 percent of U.S. PV imports.

The result? PV manufacturers globally haven’t been able to compete, Deutch and the study’s co-author, MIT professor of political science Edward Steinfeld, explain. In response, the U.S. Department of Commerce and the International Trade Commission imposed substantial anti-dumping duties — tariffs imposed on low-priced foreign imports — on some Chinese manufacturers last November, following complaints from U.S. PV manufacturers who alleged that the Chinese were selling their products below fair market value. Around the same time, Europe issued an anti-dumping inquiry; it has also threatened to announce tariffs by June 6.

China has responded with its own allegations, also threatening to issue tariffs — this time, on the materials and technology imported to make the panels. Many of those imports come from the United States. China threatens these tariffs as its PV industry also faces trouble, according to the study: Net margins of panel suppliers in China fell to double-digit negative values in 2011 and remain there now, more than a year later. The study reports that Suntech Power Holdings — the largest PV-panel maker in the world — posted a loss of $495 million in 2012. (The company declared bankruptcy at the end of March.)

Deutch and Steinfeld explain that the two nations — China and the United States — are interdependent and form a “potentially productive global ecosystem for innovation.” When one side declines — as is happening in China, with its PV manufacturers — so will the other side, as is happening in the United States, with its technology and manufacturing tools, the study says. The researchers explain that there are opportunities for the two nations to together accelerate the worldwide deployment of solar PV for electricity generation.

“The two countries have different strengths and weaknesses,” Deutch says. “The U.S. is creating the technology and manufacturing tools and China is successfully, but not profitably, manufacturing devices based on today’s technology. If both countries look at the big picture, choose to focus on their strengths, and put aside the blame game, they have a real opportunity to boost global deployment of solar.”

Arun Majumdar, the vice president for energy at Google and former director of the Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, says, “Deutch and Steinfeld’s factual and data-driven analysis shows that in the interdependent global market and supply chain of the solar industry, policies of individual governments that foster and leverage their domestic strengths to openly and fairly compete in the global market are better off in the long term to reach national goals of economic growth.”

Majumdar adds, “On the other hand, policies that distort the market via undue protectionism or disproportional investments to reach national goals could backfire and produce opposite outcomes.”

The study will become part of a larger report on the “Future of Solar,” to be released by the MIT Energy Initiative at a later date.

By: Steve LeVine

Environmental websites are buzzing that China, the world’s biggest emitter of carbon and other heat-trapping gases, is on the cusp of breaking the persistent logjam on global climate change policy by placing an absolute cap on its carbon emissions. Beijing’s impending move, writes Grist, would show that, compared with the US, “China is either the more mature of the pair, or just majorly sucking up to Mama Earth.”

The reports are inaccurate: Seven Chinese cities are enacting experimental carbon-trading programs as of 2014, and Beijing is fast reducing how much carbon is burned per unit of GDP (known as “carbon intensity”). But China hands in Beijing and the US tell me it has made no firm decision on capping absolute emissions. (The rumor began with a May 20 report by the reputable Chinese newspaper 21st Century Business Herald.)

Yet the hubbub underscores an expectation among environmentalists and others that Beijing is moving toward doing more to avoid the most catastrophic climate forecasts. Beijing already has ambitious goals for sharply reducing carbon intensity by 2015. Against the backdrop of rising local unhappiness with air pollution, China’s leadership has signaled the possibility of an even faster cleanup. Climate activists hope for another iterative jump by China—from a proportional approach to emissions reduction (reducing carbon intensity), to an absolutist strategy (a cap on total emissions).

“An absolute cap simply makes management simpler,” Deborah Seligsohn, a China expert at the University of California at San Diego, told me. “An intensity target depends on expected GDP, and so localities try to game it. They can’t game a cap.” That’s why a cap would be “a big deal domestically and internationally,” she said.

Since Deng Xiaoping launched China’s modern age in 1979, Beijing has prized economic growth over every other metric of success. No prominent expert believes that China’s emissions will decline this decade—David Fridley at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory told me that the only scenario for such a fast reduction is economic collapse or stagnation. The only hope is that China’s emissions growth can be tapered.

Many experts wonder how Chinese leaders will enact even the goals they have set. “Achieving these targets eventually would come at considerable economic cost, and so how China will strike a balance between local air pollution, which has become dire in some places, and the cost of controlling these pollutants is still unclear,” said John Reilly, an environmental economist at MIT.

Yet self-preservation is a powerful force. The tradeoff between economic growth and cutting emissions will become less stark if China’s leaders conclude that pollution is a serious political threat. Environmentalists are betting that China’s leaders will decide that it is.

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

MAY 22, 2013

As I explained earlier this week, questions related to any impact of human-driven global warming on tornadoes, while important, have almost no bearing on the challenge of reducing human vulnerability to these killer storms. The focus on the ground in Oklahoma, of course, will for years to come be on recovery and rebuilding — hopefully with more attention across the region to developing policies and practices that cut losses the next time.

The vulnerability is almost entirely the result of fast-paced, cost-cutting development patterns in tornado hot zones, and even if there were a greenhouse-tornado connection, actions that constrain greenhouse-gas emissions, while wise in the long run, would not have a substantial influence on climate patterns for decades because of inertia in the climate system.

Some climate scientists see compelling arguments for accumulating heat and added water vapor fueling the kinds of turbulent storms that spawn tornadoes. But a half century of observations in the United States show no change in tornado frequency and a declining frequency of strong tornadoes.

Does any of this mean global warming is not a serious problem? No.

It just means assertions that all weird bad weather is, in essence, our fault are not grounded in science and, as a result, end up empowering those whose prime interest appears to to be sustaining the fossil fuel era as long as possible. I was glad to see the green blog Grist acknowledge as much.

On Tuesday, I sent the following query to a range of climate scientists and other researchers focused on extreme weather and climate change:

The climate community did a great service to the country in 2006 in putting out a joint statement [from some leading researchers] on the enormous human vulnerability in coastal zones to hurricanes — setting aside questions about the role of greenhouse-driven warming in changing hurricane patterns….

In this 2011 post I proposed that climate/weather/tornado experts do a similar statement for Tornado Alley.

I’d love to see a similar statement now from meteorologists, climatologists and other specialists studying trends in tornado zones. Any takers?

Before you dive in to the resulting discussion, it’s worth reading Andrew Freedman’s helpful Climate Central piece, “Making Sense of the Moore Tornado in a Climate Context,” and a Daily Beast post by Josh Dzieza. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has posted a helpful new fact sheet, “Tornadoes, Climate Variability, and Climate Change.”

Read on for the conversation on tornadoes and global warming, with some e-mail shorthand fixed.

First, I’m posting the comments that were focused on policy, then those focused on the details of the science:

Roger Pielke, Jr., professor of environmental studies, the University of Colorado:

People love to debate climate change, but I suspect that the community’s efforts are far better placed focusing attention on warnings and response. That is what will save lives and continue the really excellent job that has been done by NOAA and the National Weather Service. I’d much rather see a community statement highlighting the importance of NOAA/NWS funding!

There will always be fringe voices on all sides of the climate debate. With the basic facts related to tornadoes so widely appreciated (unlike perhaps drought, floods, hurricanes), I think that those who see climate change in every breeze are not particularly problematic or worthy of attention.

Here are some of those basic facts:

1. No long-term increase in tornadoes, especially the strongest ones.

2. A long-term decline in loss of life (the past year saw a record low total for more than a century).

3. No long-term increase in losses, hint of a decrease.

4. To date 2013 has been remarkably inactive.

5. The Moore tornado may have been the strongest one this year, bad luck had it track through a populated area (Bill Hooke brilliantly explained the issue here).

6. That said, climatology shows that Moore sits at the center of a statistical bullseye for tornado strikes for May 20th.

Kerry Emanuel, professor of atmospheric science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (a signer of the 2006 statement):

I see the political problem with tornadoes as quite different from the hurricane problem we wrote about some years ago. To my knowledge, there are no massive subsidies to build in tornado regions, nor is insurance premium price fixing a big problem. Also, federal flood insurance is largely irrelevant to this problem. About the only thing in common is federal disaster relief, but it is hard to believe that people only build houses in huge swaths of tornado-susceptible territory because they believe they will be bailed out.

As you mention in your blog, the issues here revolve around such practical measures as safe rooms, and the role of government in mandating or subsidizing them. Perhaps one positive outcome of the latest horror story is that safe rooms in public buildings such as schools and hospitals will be mandated, given that they are apparently not all that expensive.

In my view, the data on tornadoes is so poor that it is difficult to say anything at all about observed trends, and the theoretical understanding of the relationship between severe thunderstorms in general (including hail storms) and climate is virtually non-existent. I regard this as a research failure of my profession and expect there will be a great deal more work on this in the near future. What little exists on the subject (e.g. the Trapp et al. paper from a few years ago) suggests that warming will increase the incidence of environments conducive to severe thunderstorms in the U.S. But this counts on climate models to get these factors right, and it may be premature to put much confidence in that.

Daniel Sutter, a professor of economics (focused on tornadoes), Troy University, offered the following thought after citing the Dot Earth comments of Kevin Simmons, his co-author on a recent book on tornadoes and society:

I would just add that the high cost per life saved through safe rooms which Kevin and I find in our research really indicates that tornado safety is about reducing and not eliminating risk. Safe rooms provide essentially absolute protection, but are expensive enough that many would likely judge them too expensive. We need to focus on ways to reasonably reduce risk. For instance, have engineers inspect schools and make sure the safest areas are indeed being used for shelter, or to see if there are relatively inexpensive designs that could strengthen interior hallways some.

I hate to say anything before I know for sure what the final story is from the Plaza Heights school, but the two schools yesterday appear to have provided pretty decent protection, especially since many homes around Briarwood school looked totally destroyed. Wind engineers have developed safe room designs which are great and engineering marvels, but we probably need designs that provide a good measure of safety at a portion of the price.0

Also with regard to your previous post about flimsy homes, consider the contrast between how cars and houses are marketed. Cars are sold under brand names, and we have a dual system of federal regulation of designs for safety and auto makers designing cars that are safer than federal regulations require, with certification by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Houses are mainly sold without brand names (I couldn’t tell you who built the house I own here in Alabama) with safety assurances coming through building codes. Many times we see that homes perform poorly in tornadoes or hurricanes, while during a commercial break on the Weather Channel last night there was a car ad touting the model’s crash test rating from the IIHS. If houses are indeed flimsy, there is probably a systematic reason for this. Read more…

Cirrus clouds form around mineral dust and metallic particles, study finds.

By Coral Davenport

Kerry Emanuel registered as a Republican as soon he turned 18, in 1973. The aspiring scientist was turned off by what he saw as the Left’s blind ideology. “I had friends who denied Pol Pot was killing people in Cambodia,” he says. “I reacted very badly to the triumph of ideology over reason.”

Back then, Emanuel saw the Republican Party as the political fit for a data-driven scientist. Today, the professor of atmospheric science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is considered one of the United States’ foremost authorities on climate change—particularly on how rising carbon pollution will increase the intensity of hurricanes.

In January 2012, just before South Carolina’s Republican presidential primary, the Charleston-based Christian Coalition of America, one of the most influential advocacy groups in conservative politics, flew Emanuel down to meet with the GOP presidential candidates. Perhaps an unlikely prophet of doom where global warming is concerned, the coalition has begun to push Republicans to take action on climate change, out of worry that coming catastrophes could hit the next generation hard, especially the world’s poor.

The meetings didn’t take. “[Newt] Gingrich and [Mitt] Romney understood, … and I think they even believed the evidence and understood the risk,” Emanuel says. “But they were so terrified by the extremists in their party that in the primaries they felt compelled to deny it. Which is not good leadership, good integrity. I got a low impression of them as leaders.” Throughout the Republican presidential primaries, every candidate but one—former Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman, who was knocked out of the race at the start—questioned, denied, or outright mocked the science of climate change.

Soon after his experience in South Carolina, Emanuel changed his lifelong Republican Party registration to independent. “The idea that you could look a huge amount of evidence straight in the face and, for purely ideological reasons, deny it, is anathema to me,” he says.

Emanuel predicts that many more voters like him, people who think of themselves as conservative or independent but are turned off by what they see as a willful denial of science and facts, will also abandon the GOP, unless the party comes to an honest reckoning about global warming.

And a quiet, but growing, number of other Republicans fear the same thing. Already, deep fissures are emerging between, on one side, a base of ideological voters and lawmakers with strong ties to powerful tea-party groups and super PACs funded by the fossil-fuel industry who see climate change as a false threat concocted by liberals to justify greater government control; and on the other side, a quiet group of moderates, younger voters, and leading conservative intellectuals who fear that if Republicans continue to dismiss or deny climate change, the party will become irrelevant.

“There is a divide within the party,” says Samuel Thernstrom, who served on President George W. Bush’s Council on Environmental Quality and is now a scholar of environmental policy at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. “The position that climate change is a hoax is untenable.”

A concerted push has begun within the party—in conservative think tanks and grassroots groups, and even in backroom, off-the-record conversations on Capitol Hill—to persuade Republicans to acknowledge and address climate change in their own terms. The effort will surely add heat to the deep internal conflict in the years ahead.

Republicans have been struggling with an identity crisis since the 2012 presidential election. In particular, the nation’s rapid demographic changes are forcing the GOP to come to terms with the newly powerful influence of Hispanic voters and to confront the issue of immigration. For now, climate change isn’t getting anywhere close to that kind of urgent scrutiny from Republicans, at least not in public. GOP strategists say that Republican candidates hoping to win primary races, where the electorate tends to be older and more ideologically driven, are still best served to deny, ignore, or dismiss climate change.

Today, a Republican candidate “wouldn’t be able to win a primary with a Jon Huntsman position on this,” says strategist Glen Bolger.

The problem is, as polling data and the changing demographics of the American electorate show, it’s likely that the position that can win voters in a primary will lose voters in a general election. Some day, though, the facts—both scientific and demographic—will force GOP candidates to confront climate change whether they want to or not. And that day will come sooner than they think.

Already, the numbers tell the story. Polls show that a majority of Americans, and a plurality of Republicans, believe global warming is a problem. Concern about the issue is higher among younger voters and independents, who Republicans will need to attract if they want to win elections.

According to a pair of Gallup Polls in April, 58 percent of all Americans are worried about global warming, and 57 percent believe it is caused by human activities. Not surprisingly, responses reflect a partisan divide on the issue, but among Republicans, concern about global warming is rising. Gallup found that 75 percent of Democrats worry about climate change, compared with 59 percent of independent voters (up from 51 percent in 2010) and 40 percent of Republicans (up from 32 percent from that year).

A January poll of Republicans and Republican-leading independents conducted by George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication said that a majority (52 percent) think climate change is happening; 62 percent favor taking action to combat climate change, such as taxing carbon pollution. Only 35 percent of the Republican respondents said they agree with the Republican Party’s position on climate change. (The party’s 2012 platform opposed any limits on greenhouse-gas emissions and suggested the science underlying projections of a warming climate is “uncertain.”)

Meanwhile, a March poll by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press found that 69 percent of Americans believe the climate is already changing. On the more contentious question of whether fossil-fuel pollution is causing that change, the poll uncovered a generation gap: Only 28 percent of voters over age 65 accept the scientific consensus that such emissions are warming the Earth, while close to 50 percent of those under 50 accept it.

“These polls show that there are a lot of people who are inclined to vote Republican—and believe America should respond to climate change,” says Edward Maibach, director of the George Mason program. “Republicans aren’t inclined to respond to it right now, but in the future, if they don’t take these issues seriously, they’re inclined to alienate a lot of Republican voters.”

CHRISTIAN SOLDIERS

Mother and daughter Roberta and Michele Combs are pillars of the Religious Right. Roberta, president and CEO of the Christian Coalition America, got her start in Republican politics working with celebrated strategist Lee Atwater. Michele, who was named Young Republican of the Year in 1989 and worked as a planner for events such as George W. Bush’s inauguration, is the coalition’s communications director. With their white-blond bouffant hair, penchant for fuchsia lipstick, soft South Carolina accents, and sterling conservative bona fides, the Combses are familiar presences in the ruby-red heart of the GOP establishment.

That’s why it’s so surprising to many that they are tackling climate change. But both women see global warming, and clean air and environmental protection more broadly, as issues that tie into their core conservative mission of protecting family values.

“This is an important issue for the Republican Party,” Roberta Combs says. “At one point in time, this was a Republican issue, but Democrats took it over.”

In 2010, Roberta led a Christian Coalition push for her friend Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina to sign on to a Senate climate-change bill, as the measure’s sole GOP sponsor. Graham eventually pulled his support, but thanks in part to Roberta’s pressure, he’s remained one of the few Republicans to openly acknowledge climate change and to call on his party to look for a solution. He is sticking with his position even as he prepares to face South Carolina voters for reelection next year.

“I think the Republican Party needs to embrace an environmental agenda,” Graham says. “When you ask a Republican candidate for president, what’s your environmental platform, what do they say? We need to be able to speak to this just as quickly as to do to reforming the tax code. Younger people, people under 30, this is a huge issue for them.”

Roberta was the Christian Coalition official who persuaded Emanuel, the MIT scientist, to speak with the GOP presidential candidates in January 2012. And she continues to employ her group’s grassroots muscle to muster conservative support for Republicans like Graham who support action to combat climate change, with the hope that eventually one will sponsor a bill that can pass.

“I think the Republican Party has got to move to the center. We should never leave our base, but we’ve got to be more open-minded and look at issues more American families care about,” Roberta says. “As the electorate changes, we’re not going to win as much. It’s a different generation, and the Republican Party has got to look at all of this and broaden its agenda if they want to continue to win elections.”

Last summer, Michele launched a new group, Young Conservatives for Energy Reform, aimed at amassing grassroots support for lawmakers and legislation addressing clean energy and climate change. She is channeling her network of connections among the Christian Coalition and the Young Republicans.

She works closely with Brian Smith, a 32-year-old Air Force veteran and the chairman of the Midwest chapter, who is also a former cochairman of the Young Republicans National Federation, a training ground for party leaders founded in 1931. The energy group is structured like the Young Republicans, with volunteers staffing city, state, and regional chapters. So far, the group has state chairs in Florida, Georgia, Indiana, New Hampshire, Ohio, South Carolina, and Texas—all of which have Republican governors.

Over the past year, the group has held a dozen events in those and other states. In October 2012, it sponsored a get-together in Washington for GOP congressional staff. The gatherings—mostly of young professionals in their 20s, 30s, and 40s—feature hors d’oeuvres, cocktails, and a talk from retired Marine Gen. Richard Zilmer, who makes the case that both climate change and U.S. oil dependence are matters of national security, and that policies to cut fossil-fuel use are consistent with conservative values. Emanuel has also spoken at some of the events.

The goal, Michele says, is to build a database of voters who will, at some point, come forward to back Republican candidates who support cutting carbon pollution. “We are building a grassroots army of young conservatives around the country,” she says. “When the time comes, we’ll have the grassroots to organize around candidates or legislation, and we can activate them.”

PAYING THE PRICE

What Michele and Roberta want to do, in other words, is protect lawmakers such as Bob Inglis. Today, Republicans point to the former House member from South Carolina as the textbook tale of what happens when a red-state conservative dares to acknowledge climate change.

Inglis, who left Congress in 2011, recalls the challenge his son, Rob, threw down to him a decade ago before he was to vote in his first election. He said, “I’ll vote for you, Dad, but you’ve got to clean up your act on the environment.’ ”

Inglis had never given much thought to the issue of climate change. As a by-the-books conservative, he says, “I accepted that if Al Gore was for it, I was against it, until my son challenged my ignorance on the subject.” Inglis spent the next few years educating himself on climate issues. He joined the House Science Committee and accompanied climate scientists on research trips to Antarctica and the Great Barrier Reef, where he saw firsthand the damages wrought by rising carbon pollution and warming temperatures. “I got convinced of the science,” he says, and, in 2009, Inglis cosponsored climate-change legislation with Republican Rep. Jeff Flake of Arizona. The bill proposed an idea that had strong backing from environmentalists, including Gore, as well as prominent conservative economists. It would create a tax on carbon pollution but use the revenue to cut payroll or income taxes.

Inglis would pay dearly for his support of the so-called carbon-tax swap. The following year, he lost his primary election to a tea-party candidate, Trey Gowdy. And Inglis knows his position on the climate was the reason. “The most enduring heresy was saying, ‘Climate change is real and we should do something about it.’ That was seen as a statement against the tribal orthodoxy.”

“But,” he says, “these heresies and orthodoxies change so quickly. Back in 2010, I was voting for immigration reform; look how that’s changed. It’s going to be like that with climate change.”

Along with the evolving politics of immigration reform, Bob and Rob Inglis also see in their situation a kinship with Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio, who jolted the party earlier this year when he came out in support of gay marriage. Portman changed his stance after conversations with his 21-year-old son, Will, who is gay.

“I hope there’s a parallel,” Bob Inglis says. “Rob [Portman] is a hero of mine. He loves his son. He’s willing to take risks for his son.” Unlike Inglis, Portman hasn’t yet had to face voters in a primary—and won’t until 2016. Given the rapid shift in public attitudes toward gay marriage, he may in fact suffer no repercussions. It wasn’t long ago that gay marriage served as a valuable wedge issue for the party (think George W. Bush in 2004)—much like placing limits on carbon is today.

For the moment, however, Inglis has taken on the arduous task of bringing his party back to him. Last summer, he founded the Energy and Enterprise Initiative, a nonprofit organization based at George Mason University, focused on convincing conservatives, particularly young ones, that climate change, caused by carbon pollution, is a serious threat—and on pushing for the carbon-tax swap as a fundamentally conservative economic solution. Since last fall, Inglis and a cohort of conservative economists have made their case at a dozen events, including talks at colleges and universities in Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, and Mississippi.

Last month, 21-year-old Republican Kevin Croswhite, a senior at Carthage College in Kenosha, Wis., who grew up in nearby Salem (both towns lie within in the district of Rep. Paul Ryan, the 2012 GOP vice presidential candidate) attended one of Inglis’s events—and was sold.

Croswhite has considered himself a conservative Republican since high school. As an economics major, he is a big believer in data: scientific, economic, and demographic. He is persuaded that his party’s rejection of the data on climate change will damage it politically.

“The country’s going to become more educated, and that’s not going to break our way, as a party, if we are denying what 90 out of 100 scientists say,” Croswhite argues. “If the scientific community is generally accepting of something, you need to trust that.”

While Combs’s and Inglis’s groups try to appeal to conservative Christians and young Republicans, another organization—the National Audubon Society—is reaching out to red-state conservatives in the West, linking the threat of climate change to the ideal of Theodore Roosevelt’s Republican conservatism, in a bid to appeal to hunters, fishers, ranchers, and other lovers of the outdoors. The venerable nonpartisan group has teamed with the Washington organization ConservAmerica to ask red-state voters to sign an “American Eagle Compact” calling for lawmakers to act on conservation policies, including climate change. The effort, which Audubon says is funded by a Texas Republican who has asked to remain anonymous, has so far garnered 55,000 signatures.

“We’re trying to figure out how to partner with those people, so they can turn out in communities across the country, to activate them for support,” says Audubon President and CEO David Yarnold. “We want to make sure that when Republican legislators who support conservation and climate policy go home, they’re not just getting hollered at. We want to make sure they’re hearing from reasonable conservationists who say this is not a partisan issue.”

LIGHTING THE WAY

While those groups work from the bottom up to help push Washington to move on climate issues, a constellation of prominent conservative economists is bolstering the cause. These conservatives include such intellectuals as Art Laffer, the former senior adviser to President Reagan; George Shultz, Reagan’s secretary of State; Gregory Mankiw, who was an economic adviser to the Romney campaign and the former chief economist for George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers; Douglas Holtz-Eakin, the president of the influential conservative think tank American Action Forum, a former head of Bush’s Council on Economic Advisers, and an economic adviser to Sen. John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign; and a host of other well-respected conservative economic thinkers.

Laffer spoke to National Journal by phone from his home in Tennessee, where he lives next door to Gore. The Reagan economist and the liberal global-warming crusader disagree on many issues but are united on the wisdom of a carbon-tax swap as good environmental and economic policy. “Al is a dear friend, and I think he’s a damned good public servant,” Laffer says. “I am ignorant-squared on climate change, but what I do believe is that the risks of reducing carbon in the environment are less than the risks of putting more carbon into the environment.”

Last year, Laffer wrote a detailed paper on how best to structure a carbon-tax swap, presumably as part of the broader tax-reform effort Congress appears to be moving toward. “What I believe in, and Al Gore believes in, is if you’re going to do a carbon tax, you need to offset it dollar-for-dollar with marginal tax reduction on income or employment,” he says. “Anyone who goes through what I just went through, they’ll agree with me. I’ve had more experience than anyone in the financial thinking on this.”

At the beginning of this Congress, a group of Republican lawmakers, along with a few coal-state Democrats, sponsored a measure that vowed they would never back a carbon tax, and given the antitax mood in Washington, prospects for such a tax appear dim. Still, both opponents and proponents concede that the idea will certainly be on the table if Congress makes a serious attempt at tax reform in the coming years.

Laffer said that as with so many of the policies he’s proposed before, the time will ripen for a carbon tax as it moves from impossible to inevitable. “My policies are always the North Star,” he says. “Right now, this is viewed as a third-order problem. But if we take over in 2016, this will have huge traction.”

Laffer spent last year promoting the idea on college campuses. The climate-change advocacy group Clean Air-Cool Planet flew Holtz-Eakin to New Hampshire to participate in living-room chats with voters about the economic costs of climate change and the economic benefits of addressing the problem.

In March, Schultz went to Capitol Hill to talk about climate change and push the carbon tax to congressional aides. In a standing-room-only gathering in the Rayburn House Office Building, he argued, “Good work on conservation and the environment is in the Republican genes; we’ve been the guys who did it.… My proposal is to have a revenue-neutral carbon tax.” Schultz got a standing ovation. Among the audience were staffers from the offices of Republican Reps. Phil Roe of Tennessee, Billy Long of Missouri, and Randy Neugebauer of Texas—ranked as the most conservative member of the House in a 2011 NJ survey.

A SLEEPING GIANT

It’s long been taken as a truism that the powerful oil lobby is the reason nothing happens on climate change in Washington. For many years, that was indeed true. In particular, Exxon Mobil, the nation’s largest oil company and a major contributor to Republican candidates, was associated with a campaign to fuel skepticism about climate science. From 1998 to 2006, Exxon Mobil contributed more than $600,000 to the Heartland Institute, a well-known nonprofit group that holds conferences and publishes books aimed at debunking the science of climate change. Exxon Mobil’s support of Heartland made sense. The oil company stood to take a financial hit from “cap-and-trade” climate-change proposals that would have priced carbon pollution from oil.

For a number of reasons, that equation is changing. Exxon Mobil has ended its support of Heartland’s agenda. It’s not that the oil giant has had a green awakening; it’s just that a series of internal changes have positioned the company to profit from at least some policies that price carbon emissions.

In 2010, Exxon Mobil bought the natural-gas company XTO Energy, which transformed the venerable oil producer into the world’s largest natural-gas producer. Around the same time, the company began making a noticeable shift in its climate policy. The reason: Natural gas, which is used to generate electricity, is the lowest-polluting fossil fuel, emitting just half of the greenhouse gases as coal, the world’s top electricity source. In the event of a tax on carbon pollution, demand for coal-fired electricity would freeze, while markets for natural gas would explode.

Every year, Exxon Mobil puts out a widely read report with projections on the global state of energy development. The most recent one included the assumption of a future price on carbon and a corresponding surge in natural-gas consumption. “We assume there’s going to be a price on carbon in the future, and that assumption drives our investment strategy,” says company spokesman Alan Jeffers.

And the position on climate change at Exxon Mobil that once helped fund the Heartland conferences? “We have the same concerns about climate change as everyone. The risk of climate change exists; it’s caused by more carbon in the atmosphere; the risk is growing; and there’s broad scientific and policy consensus on this,” Jeffers says.

In 2010, during Senate negotiations on the cap-and-trade bill, Exxon Mobil told the White House that it wouldn’t back that bill, but it would support legislation with a straight carbon tax, ideally, a carbon-tax swap along the lines of what Inglis and Laffer propose. Ultimately, of course, all of those attempts failed. And, today, Exxon Mobil is not actively lobbying for the tax. The company’s position remains the same, though, Jeffers says. “Our approach has been, if public policymakers have decided they want to put a price on carbon, we see a revenue-neutral carbon tax as the most efficient way to do that.”

In the 2012 campaign, Exxon Mobil gave $2.7 million in political contributions, with 88 percent going to Republicans. One of the world’s biggest and most profitable oil companies—a lobbying powerhouse and major influence in GOP politics, particularly in deep-red oil states—has accepted the science of climate change and figured out how to profit from a carbon-price policy. While Exxon Mobil won’t be leading the green revolution, its shift could make a difference in the way many Republicans approach the issue.

HEADING FOR THE HILLS

For now, however, no prominent Republican running for office in the next few years will want to get anywhere near a carbon-tax proposal, or even talk about climate change. While the rift in the party over global warming is becoming increasingly evident, most Republicans feel much more secure on the side that denies the problem.

That was made abundantly plain during the Conservative Political Action Conference in March, the annual Washington gathering that the GOP base uses to anoint its future leaders. Two leading speakers this year were Sen. Marco Rubio and former Gov. Jeb Bush, both of Florida, the state that scientists such as Kerry Emanuel warn is the most vulnerable to devastation from intensified hurricanes in the coming years.

Rubio was the undisputed star attraction, and his keynote speech sparked some of the loudest cheers when he denounced climate science in the context of condemning abortion.

“The people who are actually closed-minded in American politics are the people who love to preach about the certainty of science with regards to our climate but ignore the absolute fact that science has proven that life begins at conception,” Rubio said. A month earlier, in his response to President Obama’s State of the Union, Rubio had said, “When we point out that no matter how many job-killing laws we pass, our government can’t control the weather, [Obama] accuses us of wanting dirty water and dirty air.”

Bush’s CPAC speech had a decidedly different tone. He castigated his party for espousing hard-right views. “Way too many people believe Republicans are anti-immigrant, antiwoman, antiscience, antigay, anti-worker … and the list goes on,” he said. “Many voters are simply unwilling to choose our candidates, because those voters feel unloved, unwanted, and unwelcome in our party.”

Bush did not specifically mention climate change, although many on both sides of the aisle interpreted his remark about science as a signal that he’d be open to addressing the issue. Pundits praised the speech, but it was not a hit with his party. Bush spoke to a quiet room with a fair number of empty seats. Many in the audience members were checking their mobile devices. When he finished, Bush was met with a polite, modest smattering of applause. (Another Republican who has signaled support for climate-change legislation, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, wasn’t even invited to CPAC.)

At 41, Rubio personifies the next generation of Republican leadership, while Bush represents an older, perhaps out-of-date moderate mind-set—which means the party may very well be heading in the wrong direction when it comes to embracing climate science. Rubio’s view is likely to remain the mainstream one in the party in the short term, thanks to tea-party groups such as Americans for Prosperity, a super PAC founded by David and Charles Koch, the principal owners of Koch Industries, a major U.S. oil conglomerate.

Over the last several years, Americans for Prosperity has spearheaded an all-fronts campaign using advertising, social media, and cross-country events aimed at electing lawmakers who will ensure that the fossil-fuel industry won’t have to worry about any new regulations. The group spent $36 million to influence the 2012 elections.

“We’ve been having this debate with the Left for 10 years, and we welcome having the debate with these new groups. If there are groups who want to do a niche effort with the Republican electorate, we’ll win that debate,” says the group’s president, Tim Phillips. He’s not worried that organizations such as Combs’s Christian Coalition or economists such as Laffer will influence lawmakers—because AFP would hit any such candidate with an all-out negative campaign. “Let them bring a carbon tax on. They know it’s political death for them to bring this forward on their own.”

There’s no denying the political power of groups like Americans for Prosperity. Still, despite its massive wealth, the super PAC failed to achieve either of its two chief political goals of 2012—unseating President Obama and claiming the Senate majority for Republicans.

The goal of grassroots efforts is to persuade Republicans that they’ll be rewarded if they take a stand in support of climate action—and that they could doom their party to minority status if they don’t. Advocates in the GOP realize that it’s too early and too fraught for Republicans seeking reelection to sound the alarm over the changing climate.

But out of sight on Capitol Hill, staffers say, conversations are taking place about how to go about doing that—eventually. “Most Republicans say the same thing behind closed doors: ‘Of course, I get that the climate is changing, of course I get that we need to do something—but I need to get reelected.’ Somehow they’re going to have to find a safe place on this,” says the Audubon Society’s Yarnold.

“We’re trying to get them to come out of the climate closet,” he says. “There’s no question they’re leaving votes on the table because of this. And they know it.”

Researchers explore possible consequences of greater biofuel use

The growing global demand for energy, combined with a need to reduce emissions and lessen the effects of climate change, has increased focus on cleaner energy sources. But what unintended consequences could these cleaner sources have on the changing climate?

Researchers at MIT now have some answers to that question, using biofuels as a test case. Their study, recently released in Geophysical Research Letters, found that land-use changes caused by a major ramp-up in biofuel crops — enough to meet about 10 percent of the world’s energy needs — could make some regions even warmer.

“Because all actions have consequences, it’s important to consider that even well-intentioned actions can have unintended negative consequences,” says Willow Hallgren, the lead author of the study and a research associate at MIT’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change. “It’s easy to look at a new, cleaner energy source, see how it will directly improve the climate, and stop there without ever considering all the ramifications. But when attempting to mitigate climate change, there’s more to consider than simply substituting out fossil fuels for a cleaner source of energy.”

Hallgren and her colleagues explored some of those consequences in considering two scenarios: one where more forests are cleared to grow biofuel crops, and one where forests are maintained and cropland productivity is intensified through the use of fertilizers and irrigation.

In both cases, the researchers found that at a global scale, greenhouse-gas emissions increase — in the form of more carbon dioxide when CO2-absorbing forests are cut, and in the form of more nitrous oxide from fertilizers when land use is intensified. But this global warming is counterbalanced when the additional cropland reflects more sunlight, causing some cooling. Additionally, an increase in biofuels would replace some fossil fuel-based energy sources, further countering the warming.

While the effects of large-scale expansion of biofuels seem to cancel each other out globally, the study does point to significant regional impacts — in some cases, far from where the biofuel crops are grown. In the tropics, for example, clearing of rainforests would likely dry the climate and cause warming, with the Amazon Basin and central Africa potentially warming by 1.5 degrees Celsius.

This tropical warming is made worse with more deforestation, which also causes a release of carbon dioxide, further contributing to the warming of the planet. Meanwhile, Arctic regions might generally experience cooling caused by an increase in reflectivity from deforestation.

“Emphasizing changes not only globally, but also regionally, is vitally important when considering the impacts of future energy sources,” Hallgren says. “We’ve found the greatest impacts occur at a regional level.”

From these results, the researchers found that land-use policies that permit more extensive deforestation would have a larger impact on regional emissions and temperatures. Policies that protect forests would likely provide more tolerable future environmental conditions, especially in the tropics.

David McGuire, Professor of Ecology at University of Alaska Fairbanks, says these findings are important for those trying to implement mitigation policies to consider.

“Hallgren et al. caution that society needs to further consider how biofuels policies influence ecosystem services to society as understanding the full dimension of these effects should be taken into consideration before deciding on policies that lead to the implementation of biofuels programs,” McGuire says.

He finds Hallgren’s incorporation of reflectivity and energy feedbacks unique compared to similar studies on the climate impacts of biofuels.

Beyond the climate

While Hallgren focuses specifically on the climate implications of expanded use of biofuels, she admits there are many other possible consequences — such as impacts on food supplies and prices.

A group of her colleagues explored the economic side of biofuel expansion as part of a study released last year in Environmental Science & Technology — a paper that was recognized as that journal’s Best Policy Analysis Paper of 2012.

The team, led by Joint Program on Global Change co-director John Reilly, modeled feedbacks among the atmosphere, ecosystems and the global economy. They found that the combination of a carbon tax, incentives for reforestation and the addition of biofuels could nearly stabilize the climate by the end of the century; increased biofuels production alone could cut fossil-fuel use in half by 2100.

But just as Hallgren found trade-offs when she dug deeper, so did Reilly and his team of researchers.

“The environmental change avoided by reducing greenhouse-gas emissions is substantial and actually means less land used for crops,” Reilly says. This leads to substantial rises in food and forestry prices, he says, with food prices possibly rising by more than 80 percent.

Hallgren says, “There is clearly no one simple cause and effect when it comes to our climate. The impacts we see — both to the environment and the economy — from adding a large supply of biofuels to our energy system illustrate why it is so important to consider all factors so that we’ll know what we’re heading into before making a change.”

"The warmer climate gets, the faster the climate zones are shifting. This could make it harder for plants and animals to adjust," said lead author Irina Mahlstein.

The study is the first to look at the accelerating pace of the shifting of climate zones, which are areas of the Earth defined by annual and seasonal cycles of temperature and precipitation, as well as temperature and precipitation thresholds of plant species. Over 30 different climate zones are found on Earth; examples include the equatorial monsoonal zone, the polar tundra zone, and cold arid desert zone.

"A shift in the climate zone is probably a better measure of 'reality' for living systems, more so than changing temperature by a degree or precipitation by a centimeter," said Mahlstein.

The scientists used climate model simulations and a well-known ecosystem classification scheme to look at the shifts between climate zones over a two-century period, 1900 to 2098. The team found that for the initial 2 ° Celsius (3.6 ° Fahrenheit) of warming, about 5 percent of Earth's land area shifts to a new climate zone. The models show that the pace of change quickens for the next 2 ° Celsius of warming, and an additional 10 percent of the land area shifts to a new climate zone. "Pace of shifts in climate regions increases with global temperature" was published online in the journal Nature Climate Change on April 21.

Certain regions of the globe, such as northern middle and high latitudes, will undergo more changes than other regions, such as the tropics, the scientists found. In the tropics, mountainous regions will experience bigger changes than their surrounding low-altitude areas.

In the coming century, the findings suggest that frost climates–the coldest climate zone of the planet–are largely decreasing. Generally, dry regions in different areas of the globe are increasing, and a large fraction of land area is changing from cool summers to hot summers.

The scientists also investigated whether temperature or precipitation made the greater impact on how much of the land area changed zones. "We found that temperature is the main factor, at least through the end of this century," said Mahlstein.

This story is adapted from a news article at esrl.noaa.gov.

Researcher Eric Martinot presents findings of two-year project at campus event

Professor Eric Martinot, the senior research director with the Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies in Tokyo, told students and faculty at a seminar on April 18 that renewables have become “mainstream” and are “a major part of our energy system.”

Martinot just completed a two-year project entitled the Renewables Global Futures Report — a compilation of 170 face-to-face interviews conducted with industry executives, CEOs of renewable energy companies, utility leaders, government officials and researchers.

“We’re still thinking about the future of renewable energy like it’s 1990 or like it’s the year 2000,” Martinot said. “Our thinking is just behind the reality of where renewables are today and where they are going based on existing market technology, cost and finance trends.”

Martinot gave an overview of various projections and scenarios from the oil industry, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and environmental groups. The data shows that investment in renewables is a key example of the current growth and expected trajectory. Renewable energy investment is predicted to double if not by 2020, then by 2040.

“For the last three years, since 2010, global investment in renewable energy has exceeded investment in fossil fuels and nuclear power generation capacity. That’s very surprising to most people,” he said.

Despite this growth, Martinot said, “existing sources of finance are not going to enable us to reach high levels of renewables. Bank lending and utility balance sheet finance are the two major current finance mechanisms and they are going to run out.” In the future we should expect to see new sources of investment — including pension funds, oil companies and community funds.

Renewables currently supply about 20 percent of global electricity — with hydropower making up about 15 percent of that and all other renewables (wind, solar, geothermal and biomass) making up five percent. Martinot sees potential in expanding renewables to heating and cooling in the near future.

“We have all of the technologies we need right now, we don’t need to wait for technology for high shares of heating and cooling from renewables, but this is going to involve huge changes in building construction, architectural practices, building materials, the whole construction industry,” he explained. “It can take decades for all of that to change. But we can do it.”

Integration of renewables into the grid, buildings, homes and vehicles is where he sees the greatest opportunities for investment, infrastructure and research.

“Power grids have been operated and designed for the last 100 years on the basis of two things: number one, energy storage is impossible and number two, that supply has to meet demand,” he said. Because of the variability of renewables, integration and management of both storage and demand are necessary.

Martinot believes we are on the path toward combating these challenges. “We’re seeing both of those turned on their head because energy storage has become practical and is being done on a commercial basis on a number of projects. We’re also seeing the so-called ‘demand response’ where you can actually adjust demand to meet supply, rather than the other way around.”

Utilities in Denmark and Germany, for example, are using new tools to manage the variability of wind and solar and are able to switch to natural gas and heat when needed.

The building sector is another opportunity to integrate current renewable energy sources with the demands of the typical family home. Martinot described homes of the future that utilize solar power for heating and hot water, electric vehicles with batteries used by the home for power and energy storage, passive heat storage in building construction, and geothermal heat pumps to power homes.

“If you were able to standardize this type of construction in architectural practices around the world this could lower the cost and make if more common in peoples’ homes,” he said.

Martinot admitted he’s bullish about renewables and has high hopes that we can reduce carbon emissions and provide affordable energy.

His research shows that we can be optimistic about the future of renewables as governments, utilities and energy companies are expanding investment, research and development in renewable power across a variety of sectors.

Read Martinot's complete presentation.