News + Media

Global Change researcher Michael Greenstone and coauthors write about the importance of natural experiments" in calculating the costs and benefits of environmental regulations."

Last week, a divided court of appeals upheld what may well be the most important environmental rule in the nation's history: the Environmental Protection Agency's mercury standards. The regulation is expected to prevent up to 11,000 premature deaths, 4,700 heart attacks and 130,000 asthma attacks a year.

Critics of the mercury rule have focused on its expense. The EPA estimates it will cost $9.6 billion a year, with most of the burden falling on electric utilities. Indeed, the issue of cost is what split the court.

The Clean Air Act allows the EPA to regulate electric utilities under its hazardous air pollutants program only if it finds that such regulation "is appropriate and necessary." Focusing solely on mercury's effect on public health, the EPA made that finding.

That troubled Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh. In his dissenting opinion, he asked, quite reasonably, how the EPA could possibly conclude that regulation is "appropriate" without considering costs. He argued that it's "just common sense and sound government practice" to take account of costs as well as benefits.

But the court's majority had an answer. It noted the EPA had considered costs — not in its initial decision on whether to regulate mercury emissions but in its second and crucial decision about how stringent the regulation should be. The court's majority also emphasized the benefits of the rule, which have been estimated to be worth from $37 billion to $90 billion, outweighing the costs by a factor of between 3 to 1 and 9 to 1.

For the future, the mercury controversy offers two lessons. The first is that no approach to environmental protection can afford to be indifferent to costs. In situations where Congress allows the EPA to take account of costs, the agency should do so, at least in considering the appropriate level of stringency.

The second lesson is more subtle. Calculations of the costs and benefits of a regulation should use the best available science. In the case of mercury, for example, the substance itself is a neurotoxicant, potentially affecting memory, language, attention and cognition. But it is not easy to quantify mercury's adverse effects, and the EPA did not try.

The massive benefits identified by the EPA are expected to come not from mercury reductions but from "co-benefits" — that is, from reductions in other air pollutants that will result from efforts to reduce mercury emissions.

The vast majority of the quantified benefits of the mercury rule are a product of incidental reductions in emissions of just one other pollutant: particulate matter. That's not all that surprising, given that reductions in particulate matter, which can cause serious health problems, accounted for about one-third to one-half of the total monetized benefits of all significant federal regulations from 2003 through 2012.

In coming years, the benefits of further reductions in particulate matter will be among the most contested issues in environmental regulation. No one doubts that particulate matter is harmful to human health, but we need answers to important questions about which particles are the most dangerous and how much damage they cause at low concentrations.

Increasingly, that will involve relying on so-called natural experiments to learn about the effects of pollution on health. Such experiments ask what happens to health when some practice or event (a regulatory action, for example) causes a significant, and sometimes abrupt, change in pollution for one group of people but leaves pollution unchanged for another, similar group of people.

One such study examined the health of two similar populations in China. One consisted of people who lived north of the Huai River, who received free, government-provided coal to heat their homes. The other was made up of people who lived south of the river and did not get free coal. Those heating their homes with the free coal were found to have life expectancies 5.5 years shorter than those who did not, due to the coal-generated particulate matter they inhaled.

A greater reliance on natural experiments would be an important improvement in regulatory policy. Currently, we rely on observational studies that, while informative, don't necessarily tell us what we need to know to determine a regulation's benefits. These studies compare health in places with high and low levels of pollution. But if, say, Los Angeles has higher levels of asthma than, say, Boise, Idaho, differences in the populations — such as people's socioeconomic status or health habits — rather than differences in air pollution may be responsible. Researchers try to control for those differences with rigorous statistical methods, but it is not always easy to do so.

The court's decision to uphold the EPA's mercury rule means that the American people will be able to enjoy significant health benefits. As we celebrate that decision, we should ensure that the best science is brought to bear on decisions that affect present and future occupants of the planet.

Francesca Dominici is a professor in the department of biostatistics at the Harvard School of Public Health. Michael Greenstone is a professor of environmental economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Cass R. Sunstein is a professor at Harvard Law School; he worked on the mercury rule while serving in the Obama administration from 2009 to 2012.

The planet is a complex system in which humans are playing an ever more important role in shaping the environment and the livability of the planet. The data, modeling, and analysis of data and model results requires a variety of visualization tools. Computational resources needed for the exercise are very large. A reason for this is the inherent uncertainty in our projections, and the need to represent that uncertainty with large ensembles of model projections using Monte Carlo techniques. This then further requires decision tools and techniques that lead to decisions that are robust in the face of uncertainty.

John Reilly speaks about the growing requirement for vast computational resources in the visualization and analysis of data and model results.

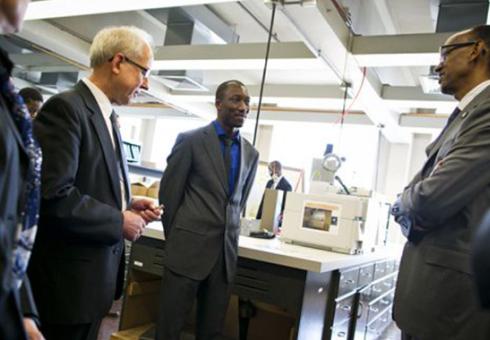

Yesterday, Paul Kagame, the president of Rwanda, visited MIT to discuss existing collaboration between his country and MIT, as well as to explore the possibility of broadening its scope. Kagame was traveling with Rwandan Ambassador to the United States Mathilde Mukantabana, Rwanda’s Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Education Sharon Haba, and others of Rwanda’s leadership.

President Kagame and his delegation, together with Maria Zuber, MIT’s vice president for research and the E. A. Griswold Professor of Geophysics, and Philip Khoury, associate provost and the Ford International Professor of History, toured the laboratory of Professor Ronald Prinn, who leads the Rwanda-MIT Climate Change Observatory Project and is the TEPCO Professor of Atmospheric Science in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences.

Rwanda and MIT are collaborating to build a world-class observatory on Mt. Karisimbi measuring climate change and the atmospheric gases forcing climate change; the observatory is ultimately to be run by local researchers. The project evolved from discussions in 2008-2009 between President Kagame, his ministers, and the MIT administration.

Mt. Karisimbi will join the MIT-led multinational Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) network that has been measuring atmospheric composition continuously over the globe since 1978. This unique new site can measure air coming from Rwanda and many other nations within and beyond Africa. Access to the 4,500-meter-high summit of Karisimbi will be facilitated by a new cable car being built for eco-tourism.

While the cable car is being built, an interim observatory has been set up on Mt. Mugogo to train the local technicians. Besides Prinn, Kat Potter, the station scientist, and doctoral student Jimmy Gasore are installing the first phase of instruments that measure temperature, winds, humidity, carbon dioxide, methane, carbon monoxide, ozone, and nitrous oxide. The second phase involves an automated mass spectrometer measuring over 50 other greenhouse gases and air pollutants. Rwandan researchers will gain the capability using computer codes to calculate regional greenhouse gas sources and sinks, climate change, and air pollution. The observatory data will be used for University of Rwanda student thesis projects, and Prinn is working with Rwandan faculty on a new Atmospheric and Climate Science master’s degree and undergraduate courses.

Rwanda will gain local capacity to adapt to climate change using the capability to forecast regional and local climate change to address the needs of local decision-makers; take advantage of revenue-yielding opportunities to mitigate climate change (such as reforestation and renewable energy using greenhouse gas sources and sink estimates); and grow a scientifically and technically educated work force that can address other important local and regional environmental and economic development issues.

Following the lab tour, Kagame and his delegation were received by MIT President L. Rafael Reif and Professor Zuber. Reif and Zuber were joined by leadership from parts of MIT that have active engagement or interest in Rwanda: the Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL); MIT D-Lab; and the MIT Energy Initiative (MITEI); and EAPS. In beginning the round-table discussion, Reif told Kagame and the rest of the meeting participants that an exploration of possibilities for new or enhanced collaboration would best center on three areas that bear directly on the well-being of Rwandans: the environment; online learning; and innovation and entrepreneurship.

MIT participants updated Kagame on current and possible engagements. Tavneet Suri, the Maurice F. Strong Career Development Professor and an associate professor of applied economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management, is the scientific director for Africa for J-PAL. She reminded Kagame of meetings held last year between J-PAL and Rwandan governmental ministers, and she described progress made on engagements currently under way; they include an effort to prevent HIV among adolescent girls, as well as work on a water-tank project. J-PAL is also helping Rwanda to build capacity for its senior civil servants and academics.

Robert Armstrong, the director of MITEI and the Chevron Professor of Chemical Engineering, provided an overview of MITEI’s work; he emphasized possibilities around solar research and work being done at MIT to explore how to provide energy for villages through the establishment of “microgrids.”

Kofi Taha, associate director of D-Lab, described the work of D-Lab and its focus on collaborating intensely with people to develop, side-by-side, the tools they need in order to improve lives. He expressed the hope that D-Lab might be helpful to the Rwandan government’s “Vision 2020,” an effort to transform Rwanda into a middle-income, knowledge-based economy by the year 2020.

Esther Duflo, the Abdul Latif Jameel Professor of Poverty Alleviation and Development Economics in the Department of Economics and founder and director of J-Pal, discussed the potential of online learning tools for teaching development economics and other subjects to those working to effect change. President Reif pointed out that though there are only a handful of Rwandan students at MIT, 1,700 Rwandans are taking courses through edX, the online learning platform founded by MIT and Harvard University.

President Kagame spoke of his desire to connect the discrete projects currently under way between MIT and Rwanda and to identify a clear set of further areas for collaboration, with Haba leading future discussions on behalf of his administration, and with the close involvement of the University of Rwanda. At the close of the meeting, Reif and Kagame agreed that the discussion showed good potential for greater collaboration.

John Reilly comments on the fortcoming IPCC report's take on slowing climate change.

Trust in technology: That seems to be the underlying message of a coming report from the world's top panel on climate change.

Scheduled for release on Sunday in Berlin, Germany, the new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report will point to many possible ways—from burying greenhouse gases to going nuclear to encouraging biofuel production—to save humanity from the ravages of climate change.

[…]

A Hard Climb

A 1992 United Nations agreement broadly obligated the world to limit global temperature increases to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) over preindustrial levels. Some studies have noted significant dangers—chiefly, lower farm production—if the planet warms beyond that point.

"The most interesting and useful thing the new report could do would be in simply laying out all the paths we could take to not breach that limit," says MIT economist John Reilly. "Most people think it's very unlikely we are going to stay within that [3.6-degree] limit."

The IPCC Working Group 3 report, based on six years of economic and technology studies, will lay out innovations and reforms in power generation, industry, transportation, farming, and other fields that might help nations to reduce emissions. Yet many of the scenarios examined in the report also look at what the world might do if the 3.6-degree limit is passed and temperatures rise still higher.

"Based on the studies that are already out there, I think we can say the sooner emissions are reduced, the easier it becomes to reach those goals," Edmonds says.

Written by 235 scientists from 53 nations over four years, the report on climate change mitigation is the third in a series released in the past year. The IPCC has released such reports in groups every six to seven years since 1990.

IPCC reports synthesize scientific studies to present policy options to government leaders. The two earlier reports enumerated the near-certain evidence that greenhouse gas emissions are responsible for increasing temperatures worldwide over the last century, and detailed the impacts on people, wildlife, and the environment.

"The IPCC is not going to solve the political problem that is at the bottom of things," Reilly cautioned. "A lot of the studies [considered] in the report started from the premise that we already were doing something about carbon reduction. That didn't happen."

John Reilly says IPCC reports should integrate science, adaptation, and mitigation efforts.

By Stephanie Paige Ogburn

ClimateWire

Every seven years, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) publishes three colossal reports about global warming.

The second of that set of three, focusing on impacts and adaptation, was just released, and on its heels have come calls for the structure of those reports to change.

On Friday, David Griggs, a professor and director of the Monash Sustainability Institute at Australia's Monash University, who has been involved in the last three IPCC reports, was the latest to weigh in with a proposal for reconfiguring the IPCC.

The comment, published in the journal Nature, addresses the burden the IPCC places on scientists, who volunteer their time, and the frequency of the reports.

Griggs argues for publishing shorter, less frequent reports, every 10 years, pointing out that the past three science reports from Working Group I have lengthened from 410 pages to 881 pages to 1,535 pages with the report released late last year.

[...]

Another past lead author, John Reilly, who is now co-director of the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has also written on some of his frustrations with the report.

Reilly, who wrote about the topic in MIT Technology Review, believes the report would be more powerful if it integrated science, adaptation and mitigation rather than producing three separate efforts.

Looking for more focus

"I think streamlining the IPCC process would be extremely important. It has gotten extremely burdensome in terms of these three separate working groups all doing a lot of work. If anything, reduce it down to a single volume that better integrates the three elements of the problem," Reilly said.

He pointed out that if someone wants to learn about how climate change is affecting tropical storms and hurricanes, he or she would have to find that information inside the publication produced by the IPCC's Working Group I, which is focused on science.

"Then if you want to figure out how to adapt to them, you have to go to Working Group II and dig into several chapters," Reilly added.

Read more...

John Reilly

Co-director MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change

The difficulty of predicting local effects of climate change makes a compelling case for preventing it.

This week the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a major report focused on what actions might or could be taken to adapt to climate change. It attempts to describe who and what is especially vulnerable to climate change, and gives an overview of ways some are adapting.

The report makes clear that specific estimates of how climate change will affect places, people, and things are very uncertain. Brought down to a local level, climate change could go in either direction—there are risks that a given area could get drier or wetter, or suffer floods or droughts, or both. This uncertainty makes efforts to prevent climate change even more important.

Specific risks to natural systems are well documented by the report. It finds, for example, the greatest risks are to those ecosystems, people, and things in low-lying coastal areas, because expected sea-level changes are in only one direction, up. This is also the case in the Arctic, where the temperature rise is expected to be much greater than the global average. There is good science and unanimous agreement among climate models behind these assertions.

But a frustrating aspect of the report—and a reflection of the difficulty of working in this line of research—is that very few specific risks to humans are quantified in a meaningful way. For example, one might ask: has my risk of death increased because of more hot days? The report says, “Local changes in temperature and rainfall have altered the distribution of some water-borne illnesses and disease vectors (medium confidence).” This seems to state the obvious, while giving no indication of whether the alterations may have increased or decreased risk or what the magnitude of the alteration might be. Given that the statement seems to say little, it is hard to imagine there is not high confidence.

The report does conclude with high confidence risks to low-lying coastal areas: emergencies during extreme weather, mortality from heat, food insecurity, loss of livelihood in rural areas due to water shortage and temperature increases, loss of coastal ecosystems and livelihoods that depend on them, and loss of freshwater ecosystems. But again, this high confidence comes with an absence of quantification of how many/much and the degree of risk. Will extreme weather double, triple, or quadruple the number of extreme emergency weather-related events of a given magnitude (dollars or lives lost)? Will it increase these incidences by 10 percent, or will some areas face increased risk while other areas face reduced risk?

In the end, the report is a compendium of things that might happen or are likely to happen to someone or something, somewhere. But what does this actually mean for me, or anyone who might read the report? I would avoid beachfront property. If my livelihood depended on a coastal resource, I would try to find a different job, or at least urge my children to pursue another line of work.

That is where a measure of wealth brings some resilience—I have those options, others do not. The report “quantifies” in some sense by establishing an element of “relative risk,” concluding that the poor and marginalized in society are more vulnerable because they do not have the means to adapt. Beyond this, it is not clear that climate prediction is at a high enough level to offer information that I can use to take concrete actions for most day-to-day decisions and investments.

What the report does provide is some documentation of adaptation in action—what different regions, cities, sectors, and groups are doing to adapt—concluding that there is a growing body of experience from which to learn.

However, perhaps the greatest truth in the report is in the following statement:

“Adaptation is place and context specific, with no single approach for reducing risks appropriate across all settings (high confidence). Effective risk reduction and adaptation strategies consider the dynamics of vulnerability and exposure and their linkages with socioeconomic processes, sustainable development, and climate change.”

Hence, while it’s possible to learn from others’ adaptation experiences, in the end, the specifics of climate change in my place, given my circumstances, and the socio-economic environment in which I live will present me with very different climate outcomes and opportunities to adapt than you will have where you live.

This fact alone raises the cost of adaptation, because to some degree each recipe needs to be invented anew. What worked in the past likely won’t work in the future—or at least, not as well. And we need to process a lot of highly uncertain climate projections in developing the new recipe.

The report also concludes, not surprisingly, that risks increase and extend to more people, places, and things if the global temperature rise is three degrees Celsius or greater than if there is only a one-degree rise. Overall, the report provides, in my judgment, a compelling case for more serious mitigation efforts—the topic of the next IPCC report, to come out later this month.

John Reilly is the co-director of the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.

By Oguzhan Ozsoy

Anadolu Agency

There are currently 14 nuclear power plants in operation with 8 more under construction in China, wind energy is thirds largest energy source. China the largest consumer of coal in the world is attempting to diversify its energy sources to move towards renewable energy in particular, wind and nuclear power.

[...]

China's nuclear power generation should increase over the next few years, according to Energy expert Michael Davidson, from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

"This is part of a concerted effort to introduce renewable and other non-fossil fuel energies into the electricity mix to reduce China's reliance on coal," he said adding that "wind benefited from a stable feed-in-tariff". It appears that there will be an increase in reliance on both wind and nuclear energy in the country over the next few years.

Davidson anticipates that electricity generated through nuclear energy could overtake that generated from wind energy by the end of 2015," said Davidson, who works on the China Energy and Climate Project in MIT, adding that China is committed to expanding nuclear power as well, however, the nuclear industry grew slower than wind due to its lengthy construction and time-consuming approval processes.

Davidson confirmed that the current nuclear power generation should increase over the next few years as there are 14 nuclear power units in operation in China with 8 plants under construction and in preliminary preparation with approval, according to China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC).

More...

By Genevieve Wanucha

Oceans at MIT

The ocean plays a critical role in climate change, especially in setting the climate's response to increasing anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases. As excess heat accumulates in various parts of the Earth system, most of that thermal energy goes into the ocean instead of into the lower atmosphere and land.

“We can compare the ocean to a cold compress that a parent applies to the forehead of a child with a fever,” says Yavor Kostov, a graduate student in the Program in Atmospheres, Oceans, and Climate (PAOC) within MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS). “In that this wet towel can absorb some of the heat, giving partial relief until the towel itself becomes saturated with heat.” Similarly, the ocean’s enormous capacity to store heat temporarily slows down global warming.

In recent years, a hot topic in climate science has arisen over the fact that climate models vary widely in their representation of ocean heat uptake. The oceans in some models absorb more or less heat in high-latitude regions such as the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean; some store heat at different depths. According to two new papers published in Geophysical Research Letters, those details matter a great deal to the predictions of global warming over the coming centuries.

Understanding ocean circulation

One of these papers focuses on the deep overturning circulation in the North Atlantic Ocean, better known as AMOC, which transports and buries atmospheric heat in the ocean. Kostov, working with Kyle Armour, an EAPS postdoc, and John Marshall, MIT professor of oceanography, investigated how the various assumptions about this major ocean feature affect model predictions. To do so, he compared a set of new-generation models that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) uses in their projections.

Kostov found that models featuring a deeper and stronger AMOC have a greater capacity to store heat and delay long-term global warming due to increasing levels of carbon dioxide. In other words, a stronger overturning circulation in a model tends to promise a cooler world in one hundred years.

There are other even greater sources for the differences in climate predictions across models, such as cloud responses to greenhouse gases, Kostov notes, “but all aspects of the climate system are important, and we have to take into account the role of the ocean in order to improve our predictions for future warming.”

These results led the MIT group to conclude that models must better represent the AMOC and its future changes, based on real-world measurements that extend over time and geographical location. Unfortunately, there is not a long record of observations in the AMOC, thanks to the enormous technical difficulty of probing the ocean’s deep layers. However, Kostov notes his excitement that a few large-scale oceanographic projects, including U.K. RAPID and U.S. CLIVAR, have started to continuously monitor how the circulation varies with depth in an effort to fill this scientific void.

Climate connection

Along with depth, the geographical location of ocean heat uptake matters to climate change. Observations suggest that much of the heat enters the ocean in high-latitude regions such as the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean. In 2010, modeling by Michael Winton of the NOAA/Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory showed that ocean heat uptake at high latitudes tends to cool the Earth significantly more than heat uptake in tropics. Yet, it is unclear why heat uptake at the poles provides the most efficient air conditioning for the entire planet or how this sensitivity should be represented in models.

Offering an explanation is Brian Rose, MIT PhD ‘10, an assistant professor at the SUNY Albany Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, along with MIT's Kyle Armour and David Battisti, professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington, whose new study implicates the activities of low lying clouds above the ocean. Using idealized configurations of several IPCC models, they found that when heat enters the ocean in the tropics, clouds change shape to allow more sunlight to be absorbed by the planet. This cloud transformation doesn't happen in the high latitudes, which the authors suggest as a potential reason why heat uptake in these regions is so good at cooling the planet.

“The authors show that valuable insights can be gained by considering the atmospheric response to an imposed change in the ocean,” comments Timothy Merlis, Assistant Professor at McGill University, who was not involved in the study. “And it will be important to understand why the clouds respond differently to the different regions of ocean heat uptake.”

Ultimately, the study critiques how the field uses observations in estimating the climate’s sensitivity to greenhouse gases. "A common way to calculate climate sensitivity simply combines recent observations of global surface temperature changes, heat uptake, and greenhouse gas forcing," says Armour, "which misses the details of how heat is getting into the ocean. One implication is that we can’t actually estimate long-term warming from present-day observations unless we take into account how the pattern of ocean heat uptake might change with time."

And change it will. For example, the Southern Ocean takes up a lot of heat now. But as the ocean warms over hundreds to thousands of years, the deep ocean currents will become saturated with heat and the Southern Ocean heat sink will eventually shut off. “Neglecting to account for where heat enters the ocean means that we could experience much more warming than anticipated,” Armour says.

Showing how we must look up to the clouds and down to the deep North Atlantic to improve long-term predictions of global warming, these studies converge in a new case for ocean-enlightened climate modeling.

Photo: WHOI/Knorr Cruise, KN178

Genevieve Wanucha

Oceans at MIT

John Marshall, Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Oceanography, recently accepted the 2014 Sverdrup Gold Medal of the American Meteorological Society for his “fundamental insights into water mass transformation and deep convection and their implications for global climate and its variability."

Marshall is an oceanographer with broad interests in climate and the general circulation of the atmosphere and oceans, which he studies through mathematical and numerical models of physical and biogeochemical processes. His research has focused on problems of ocean circulation involving interactions between motions on different scales, using theory, laboratory experiments, and observations as well as innovative approaches to global ocean modeling pioneered by his group at MIT.

The Sverdrup Gold Medal recognizes Marshall’s influential ideas about deep convection in the ocean, the process by which, in certain polar regions, cooling water descends, transporting properties such as oxygen, salt, carbon, and heat into the ocean’s deep interior. Marshall, in a 1990s collaboration with his graduate students Sonya Legg and Helen Hill, née Jones, and the late Professor Friedrich Schott of the University of Kiel, in Germany, demonstrated that the convective process in the ocean occurs slowly enough for it to be influenced by Earth’s rotation. This insight overturned the prevailing view that convection in the ocean was an upside-down version of atmospheric convection.

Marshall’s work on rotating convection in water mass transformation triggered a vast amount of research, including the Labrador Sea Deep Convection Experiment, a major field program in 1996 that provided the most comprehensive set of measurements of ocean convection. The dataset collected on this international expedition led to insights into the convective process in the ocean and its representation in models in light of Marshall’s theoretical descriptions. This body of work also motivated the development of the MIT General Circulation Model (MITgcm), which Marshall’s group first used to simulate deep convection fluid dynamics at high resolution. The algorithms used to represent convection drive the modern-day MITgcm, one of the most widely used global ocean models in the world.

To gain a broader understanding of Earth’s fluid dynamical system, Marshall shifted focus to contemporary issues in global ocean circulation. “I’ve always tried to move forward,” Marshall says. “Even though this work on water mass transformation was enjoyable, I stopped it and moved on to study the role of the Southern Ocean in climate.” Marshall has now spent 10 years revising the scientific understanding of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC). In particular, his updated modeling shows that the ACC brings up deep water and buried carbon to the surface around Antarctica, leading him and colleagues to suggest that the Southern Ocean is the window by which the interior of the ocean connects to the atmosphere, and is thus a powerful mediator of climate.

Professor Marshall received a PhD in atmospheric sciences from Imperial College London in 1980. He joined MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences in 1991 as an associate professor and has been a professor in the department since 1993. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 2008. He is coordinator of Oceans at MIT, a new umbrella organization dedicated to all things related to the ocean across the Institute, and director of MIT’s Climate Modeling Initiative (CMI).