The Christian Science Monitor writes about an MIT climate change study released Sunday, indicating that the cost of slashing coal-fired carbon emissions would be offset by reduced spending on public health. The EPA-funded study examined climate change policies similar to those proposed by the Obama administration in June.

Jared Gilmour

Christian Science Monitor

President Obama’s controversial plan to phase out coal and slash carbon emissions is an expensive one. But a new study suggests it could be cheaper than the alternative: pollution, poor air quality, and accompanying health costs.

Cutting emissions might lower health spending so drastically that the US could end up saving ten times more than it would cost to implement carbon reductions, according to a Massachusetts Institute of Technology study published Sunday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

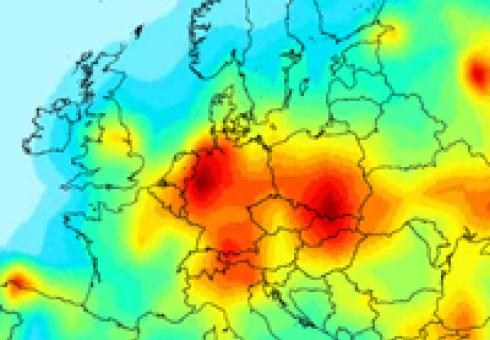

Environmentalists have long argued that curbing pollution is good for protecting local habitats and public health. Recently, though, the push for tighter environmental protections has sometimes shifted the focus from human health and conservation to climate change. The MIT study ties both environmental paradigms together, demonstrating how policies targeting carbon emissions can boost public health by reducing the more conventional pollutants emitted alongside greenhouse gases. Those conventional pollutants include particulate matter and carbon monoxide, which officials link to increased incidence and severity of illnesses like asthma, heart disease, and lung cancer.