News + Media

Keeley Rafter

Engineering Systems Division

Noelle Selin, assistant professor of engineering systems and atmospheric chemistry, along with Amanda Giang (Technology and Policy Program graduate) and Shaojie Song (Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences PhD student), recently traveled aboard the specialized NCAR C-130 research aircraft as part of a mission to measure toxic pollution in the air.

The team participated in the Nitrogen, Oxidants, Mercury and Aerosol Distributions, Sources and Sinks (NOMADSS) project. The NOMADSS project integrates three studies: the Southern Oxidant and Aerosol Study (SOAS), the North American Airborne Mercury Experiment (NAAMEX) and TROPospheric HONO (TROPHONO). Selin’s group focuses on the mercury component.

“Mercury pollution is a problem across the U.S. and worldwide,” Selin says. “However, there are still many scientific uncertainties about how it travels from pollution sources to affect health and the environment.”

Selin and her students used modeling to inform decisions about where the plane should fly and to predict where they might find pollution. Their collaborators at the University of Washington aboard the aircraft captured and measured quantities of mercury in the air, conducting a detailed sampling in the most concentrated mercury source region in North America.

“It was really exciting to experience first-hand how measurements and models could support each other to address key uncertainties in mercury science,” Giang says.

The main objectives of this project include constraining emissions of mercury from major source regions in the United States and quantifying the distribution and chemical transformations of mercury in the troposphere.

NOMADSS is part of the larger Southeast Atmosphere Study (SAS), sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in collaboration with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Electric Power Research Institute. This summer, the Southeast Atmosphere Study brought together researchers from more than 30 universities and research institutions from across the U.S. to study tiny particles and gases in the air from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean, and from the Ohio River Valley to the Gulf of Mexico. The study aims to investigate the relationship between air chemistry and climate change, and to better understand the climate and health impacts of air pollution in the southeastern U.S.

July 29, 2013

Alli Gold Roberts

MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change

Phytoplankton — small plant-like organisms that serve as the base of the marine ecosystem — play a crucial role in maintaining the health of our oceans by consuming carbon dioxide and fueling the food web. But with a changing climate, which of these vital organisms will survive, and what impact will their demise have on fish higher up the chain?

Stephanie Dutkiewicz, a researcher with the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, and her colleagues developed a model that investigates the potential effects of climate change on phytoplankton.

“Our model is unique because we were able to include 100 different species of phytoplankton, where almost all other models include just three or four,” Dutkiewicz explains. “This diversity of species allows us to analyze the ecological effects of climate change and how species will shift, adapt, thrive or die off.”

Once Dutkiewicz and her team built their phytoplankton model, they integrated it with a 3-D model of the global ocean system that is part of the Joint Program’s Integrated Global System Model (IGSM) 2.3. This comprehensive model allows the researchers to study temperature, light and circulation in terms of both the large consequences to the ocean system as a whole and the small responses individual phytoplankton have with each other.

“This model gives a nice demonstration of the complexity of the system and how you can’t just look at one piece of it to see what’s going to happen,” Dutkiewicz says.

Dutkiewicz gives an example: If a researcher just looks at the effects from a change in temperature, they would find that phytoplankton would be more productive. But when studying the whole picture, that is not the case.

On a global scale, and in the most extreme climate scenario, Dutkiewicz finds that by the end of the century half the population of phytoplankton that existed at the beginning of the century will have disappeared and been replaced by entirely new phytoplankton species.

“There will still be phytoplankton in any part of the ocean, they’ll just be different and that is going to have impacts up the food chain,” Dutkiewicz says.

Globally ocean productivity may not change much, as different impacts of changing climate might balance each other out, Dutkiewicz’s research shows. But looking regionally paints an entirely different picture. In the tropics and higher latitudes, a decrease in the nutrients these small organisms need to survive will limit phytoplankton growth. Meanwhile, in the upper latitudes, the ocean temperatures are expected to rise, spurring phytoplankton growth.

“The take home message is, studying these complex climate interactions is not simple and trying to make it simple will give you the wrong answer,” Dutkiewicz says.

Now that Dutkiewicz has built this complex marine ecosystem model, she is planning to apply it to new research. In fact, she has already added an additional type of phytoplankton that’s a nitrogen fixer, meaning it converts nitrogen into a useable form to help feed other organisms. She plans to assess how this species has changed over time. Dutkiewicz is also assessing the impacts of iron, an important nutrient in absorbing CO2, on phytoplankton populations.

Coal has been the primary fuel behind China's economic growth over the last decade, growing 10 percent per year and providing three quarters of the nation’s primary energy supply

By Michael Davidson

Coal has been the primary fuel behind China’s economic growth over the last decade, growing 10 percent per year and providing three quarters of the nation’s primary energy supply. Like China’s economy, coal’s use, sale and broader impacts are also dynamic, changing with technology and spurring policy interventions. Currently, China’s coal sector from mine to boiler is undergoing a massive consolidation designed to increase efficiency. Coal’s supreme position in the energy mix appears to be unassailable.

However, scratch deeper and challenges begin to surface. Increasingly visible health and environmental damages are pushing localities to cap coal use. Large power plants with greater minimum outputs are shackling an evolving power grid trying to accommodate new energy sources. Further centralization of ownership is rekindling decade-old political discussions about power sector deregulation and reform

This unique set of concerns begs the question: how long will coal remain king in China’s energy mix?

Read the rest at The Energy Collective...

This analysis is part of a new blog by MIT student Michael Davidson hosted by The Energy Collective on “Transforming China’s Grid.” Follow the blog here: http://theenergycollective.com/east-winds

New research in China quantifies the relationship between reduced life expectancy and elevated air pollution from coal fired boilers. MIT professor Michael Greenstone tells host Steve Curwood that residents in the north of China live 5 years less on average than those in the south as a result of higher exposure to air pollution from coal combustion.

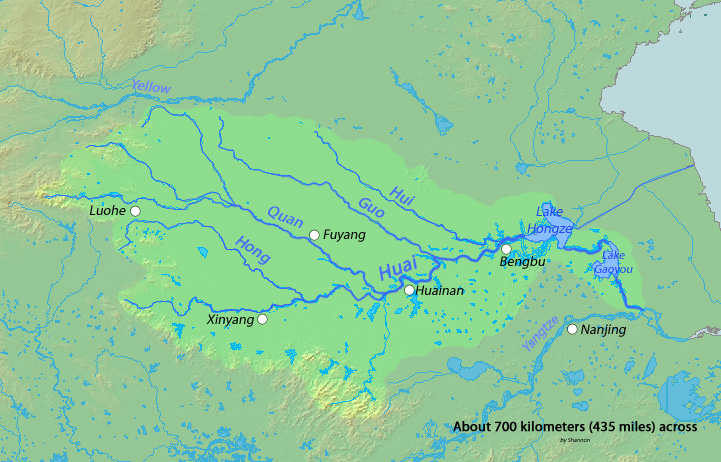

Air pollution has taken a toll on the health of Chinese residents. A person living in the north of the River Huai can expect to lives 5 years less than a person south of the river, an unintended legacy of the government’s policy to give free coal for winter heating in the north of the country. (US Embassy)

New research in China quantifies the relationship between reduced life expectancy and elevated air pollution from coal fired boilers. MIT professor Michael Greenstone tells host Steve Curwood that residents in the north of China live 5 years less on average than those in the south as a result of higher exposure to air pollution from coal combustion.

Transcript:

CURWOOD: Highly polluted air is bad for your health, and that's particularly true when it's air full of small particles from coal-fired power plants, as studies going back for years have shown. But just how bad? Now for the first time, there's a study that actually quantifies how many years of life expectancy are lost to a given amount of particulate exposure. Michael Greenstone is a Professor of Environmental Economics at MIT. He recently published a paper that compared two populations in China that experienced very different levels of polluted air.

GREENSTONE: The basis of the study comes from a Chinese policy that was implemented during the Planning Period.

CURWOOD: This was back in the 1980s we’re talking about.

GREENSTONE: It dates really from the 1950s to the 1980 period, although the legacy of the policy remains to date. But they didn’t have enough money to provide winter heating for everybody, so they somewhat arbitrarily decided that people who live north of the Huai River, which bisects the country into north and south, would have free winter heating, and that was provided through free coal and building the infrastructure to combust the coal to create heat. And the basis of the study is to compare people who live just north of the river with people who live just to the south of the river. And I should add, in the south, it was forbidden to build heating units.

So what the study did then is it got data from 1981 to 2000 on pollution, and what we find is pretty dramatic. Living north of the river led to almost 200 micrograms per cubic meter increase in total systemic particulates. Now, of course, most people aren’t familiar with those units, so to put it in context, it was about 350 micrograms per cubic meter in the south, and 550 micrograms per cubic meter in the north, and by comparison, the US average right now is probably 40 or 50. So both the levels are enormous, and the difference between the north and south is also enormous.

CURWOOD: So what did you find when you compared life expectancy for residents in the north versus the south?

GREENSTONE: It’s remarkable. So, as I mentioned, just at the river’s edge there’s a jump up in particulates concentrations, and that’s matched by a jump down in life expectancy. Specifically, what we found is people who live north of the Huai River, and were the intended beneficiaries of these policies, have life expectancy about five-and-a-half years less than people who live to the south.

CURWOOD: How many people live in that area to the north?

GREENSTONE: In north China there’s about 500 million people, and so, from that, we deduced that the policy is causing a loss of approximately 2.5 billion life years.

CURWOOD: What kind of illnesses? What kind of deaths were these people going through?

GREENSTONE: All of the effects appear to be coming from elevated mortality rates due to cardiorespiratory causes of disease that are plausibly related to air pollution. So, lung cancer, heart attacks, other respiratory diseases. In contrast, we find no affect on mortality rates associated with causes of death that are non-cardiorespiratory.

CURWOOD: Where you able to break out just how much particulate would lead to just how much lower life expectancy?

GREENSTONE: Yes. So, in particular what we find is that an extra hundred micrograms per cubic meter of total suspended particulates is associated with a loss of life expectancy of about three years. And why that’s important is that that can be applied to other settings, both in other countries, and in other parts of China as well.

CURWOOD: Now the wind can carry air pollution from China across the Pacific Ocean to North America. Should people, say, in California be concerned about air pollution from China?

GREENSTONE: There’s always a concern about that, and it would definitely be the smaller particles that would be able to travel that far. I think probably the larger concern for Americans and really everyone who lives on the planet are the increasing rates of carbon dioxide emissions coming from China, which is a completely different pollutant, but is also associated with the combustion of coal and is causing climate change.

CURWOOD: So you don’t worry so much about particulates, you worry about CO2.

GREENSTONE: Yes. I mean, it’s worth emphasizing that China consumes more than half of the world’s coal.

CURWOOD: So what policies does China have now regarding this use of free heat in the north? And what are they doing to address the obvious public health problem?

GREENSTONE: Yes, so the legacy of the policy continues. It’s not quite in the same form. I don’t think the government is running around installing boilers anymore, but they continue to subsidize coal in the north. As an example, I’ve lectured at a university in Chengdu which is a city that’s in the south but it’s in the northern part of the south so they have cold winters. And it was just normal occurrence that when I was lecturing there was no heat in the building and all the students were wearing winter coats. So the legacy of this policy continues today. With respect to policy looking forward, I think what this study has helped to highlight is that consequences of air pollution in terms of human health are greater than what had been previously realized. And perhaps it will tilt the balance as they try to devise the optimal tradeoff between air pollution and increasing incomes.

CURWOOD: What has been the response to your study in China, privately as well as publicly?

GREENSTONE: Two of my co-authors are Chinese. One of them reported that on his microblog he had 300,000 hits in the first eight hours, and that was in response to a post describing the results. I think in the coming days and months, it will be very interesting to see what the impacts are, and the degree to which it affects Chinese policy. Candidly, China has an opportunity here to greatly improve the health of its citizens.

CURWOOD: Michael Greenstone is Professor of Environmental Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Thanks so much, Professor Greenstone.

GREENSTONE: Thank you for having me.

Ahead of the World Energy Conference (WEC) in Daegu, South Korea, Siemens is hosting a series of panels throughout the world as part of a "Road to Daegu" series. The results of this exciting journey through the energy systems of the world will be presented at the WEC on October 13-17.

Joint Program Co-Director John Reilly participated in the U.S. panel on July 9th in Florida. The panel was on "Affordable and sustainable energy for the USA: Competitive advantage for the future?"

He was joined by Tom Kuhn, President of the Edison Electric Institute;

About the Panel

Affordability, security and sustainability are the three goals most countries are pursuing when it comes to their energy supply. In the U.S., there is a strong focus on affordability, and energy prices have always been low compared to international levels. And this is even more so today than ever before: The country’s “shale revolution” is slashing natural gas prices to all-time lows.

But can the U.S. achieve both goals – affordability and sustainability? This was the opening question at our third Round Table discussion with Michael Süß, this time held at the headquarters of Florida Power & Light in Juno Beach, Florida...

For John Reilly, Senior Lecturer at the renowned Sloan School of Management of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the efforts being undertaken in the U.S. on behalf of the environment aren’t enough. “We are a wealthy society in the U.S. and don’t have a real affordability problem in regard to energy prices – but what we can’t afford is not to be sustainable.”...

Read more...

Watch the panel's recap...

Watch the panel in full...

With global warming, a study finds, tropical cyclones may become more frequent and intense.

Existing research suggests that hurricanes could become stronger but less frequent thanks to climate change. But a new study says both could happen.

(Also covered by USA Today)

By: Bryan Walsh

Maybe Mayor Michael Bloomberg would have gone through the troubling of putting together a 430-page report outlining a $19.5 billion plan to save New York from the threat of climate change had Hurricane Sandy not hit last year and inflicted some $20 billion in New York City alone. But somehow I doubt it. There’s a reason that a satellite image of Hurricane Katrina highlighted the poster for An Inconvenient Truth, or that belief in man-made global warming tends to spike after extreme weather. Heat waves are uncomfortable and drought is frightening, but it’s superstorms—combined with the more gradual effects of sea-level rise—that can make climate change seem apocalyptic. Just read Jeff Goodell’s recent piece in Rolling Stone about what a major hurricane might be able to do to Miami after a few decades of warming.

But there was one hopeful side effect to climate change, at least when it came to tropical storms. The prevailing scientific opinion—seen in this 2012 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—is that while tropical storms are likely to become more powerful and rainier as the climate warms, they would also become less common. Bigger bullets, slower gun.

A new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, however, suggest that we may not be so lucky. Kerry Emanuel, an atmospheric scientist at the Massachusetts institute of Technology (MIT) and one of the foremost experts on hurricanes and climate change, argues that tropical cyclones are likely to become both stronger and more frequent as the climate continues to warm—especially in the western North Pacific, home to some of the most heavily populated cities on the planet. But the North Atlantic—meaning the U.S. East Coast and Gulf Coast—won’t be spared either. Bigger bullets, faster gun

Emanuel is going up against the conventional wisdom and much of the published literature with this paper. But the reality is that we don’t have a very good grasp of how tropical cyclone formation or strength might change in the future. As Adam Freedman points out at Climate Central, hurricanes may be huge, but they’re still too small to be easily tracked by computer climate models, which do better on a larger scale. Emanuel embedded higher-resolution regional and local models into an overarching global framework. Emanuel’s “downscaled” model simulates the development of tropical cyclones at a resolution that will increase as the storm gets stronger. For each of the six IPCC global climate models, Emanuel simulated 600 storms every year between 1950 and 2005, then ran the model forward to 2100, using an IPCC forecast that has global carbon dioxide emissions tripling by the end of the century.

Emanuel’s simulations found that the frequency of tropical cyclones will increase by 10 to 40% by 2100. And the intensity of those storms will increase by 45% by the end of the century, with storms that actually make landfall—the ones that tend to smash—will increase by 55%. As Emanuel told LiveScience:

We see an increase, in particular, toward the middle of the century. The results surprised us, but we haven’t gotten so far as to understand why this is happening.

OK, big caveats here. Emanuel is a very well-respected climatologist, but it always takes more than a single study to overturn existing scientific opinion—especially if that opinion is itself a little wobbly. Georgia Tech climatologist Judith Curry, who falls on the more skeptical side of the scientific debate on climate change, told this to Doyle Rice of USA Today:

The conclusions from this study rely on a large number of assumptions, many of which only have limited support from theory and observations and hence are associated with substantial uncertainties. Personally, I take studies that project future tropical cyclone activity from climate models with a grain of salt.

We’ll see in the decades to come whether Emanuel is right. But in a way, it may not matter all that much. As Sandy showed, hurricanes already pose a tremendous threat to our coastal cities. And that threat will continue to grow no matter what climate change does to tropical storm frequency or intensity because we’re putting more and more people and property along the water’s edge. Remember Miami? In 1926 the city was devastated by a Category 4 hurricane. (Sandy barely ranked as a Category 1 by the time it made landfall.) The difference is that there wasn’t much of a Miami back in 1926—the city’s population had just passed 100,000. Today more than 2.5 million people call Miami-Dade county home, and a hurricane of the same sort that hit in 1926 that hit now would cause $180 billion in damages. Whatever climate change does to hurricanes, we need to be ready.

This is the first post of a multi-part series on Transforming China’s Grid, where Michael Davidson will be critically examining China’s efforts to reinvent and decarbonize its power sector and related energy goals. He begins with China’s efforts to create provincial and city-level carbon trading pilots as well as major obstacles to establishing a national system that can link with other ETS markets.

By Michael Davidson

China’s first mandatory carbon emissions trading system (ETS) pilot debuted last month before a packed auditorium in the southern city of Shenzhen. China’s first official carbon trade was greeted with fanfare and a well-choreographed script of climate officials. Shenzhen is the first of seven cities and provinces expected to unveil cap-and-trade programs in China this year, which drew skeptical reactions from foreign onlookers based on the first day’s low volume – 21,120 tons at 28-30 yuan / ton ($4.55-$5.05).

The ETS pilots are a small market-based component of a broader climate policy that has historically relied on administrative measures carried in five-year plans. The overriding priorities for provincial officials are energy and carbon intensity reduction targets, most recently allocated in 2011. Nationally, these amount to 16% and 17% reductions in energy use and carbon emissions per unit GDP, respectively, by 2015; a 40-45% carbon intensity reduction below 2005 levels by 2020. However, ensuring an early emissions peak (i.e., before 2030) will require more flexible approaches, in particular, market mechanisms, for which the ETS pilots are a useful bellwether. While the merits of the pilots should not be judged by the first trading day, significant obstacles stand in the way of creating a national ETS by 2016, as currently envisioned by the Chinese leadership. Even before the remaining six trading pilots ring the opening bell, we have a good sense of what these obstacles will be.

Read the rest on The Energy Collective...

Ahead of the World Energy Conference (WEC) in Daegu, South Korea, Siemens is hosting a series of panels throughout the world as part of a "Road to Daegu" series. The results of this exciting journey through the energy systems of the world will be presented at the WEC on October 13-17.

Joint Program Co-Director John Reilly participated in the U.S. panel on July 9th in Florida. The panel was on "Affordable and sustainable energy for the USA: Competitive advantage for the future?"

A new study links heavy air pollution from coal burning to shorter lives in northern China.

(Also covered by WSJ, WaPo, NYT, Reuters, Bloomberg, LA Times, Nat Geo, Nature, Discover, CNN, BBC, Guardian, Sky News, International Business Times, Financial Times, The Telegraph, Daily Mail, China.org)

By Lousie Watt

BEIJING (AP) — A new study links heavy air pollution from coal burning to shorter lives in northern China. Researchers estimate that the half-billion people alive there in the 1990s will live an average of 5½ years less than their southern counterparts because they breathed dirtier air.

China itself made the comparison possible: for decades, a now-discontinued government policy provided free coal for heating, but only in the colder north. Researchers found significant differences in both particle pollution of the air and life expectancy in the two regions, and said the results could be used to extrapolate the effects of such pollution on lifespans elsewhere in the world.

The study by researchers from China, Israel and the United States was published Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

While previous studies have found that pollution affects human health, "the deeper and ultimately more important question is the impact on life expectancy," said one of the authors, Michael Greenstone, a professor of environmental economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

"This study provides a unique setting to answer the life expectancy question because the (heating) policy dramatically alters pollution concentrations for people who appear to be of otherwise identical health," Greenstone said in an email. "Further, due to the low rates of migration in China in this period, we can know people's exposure over long time periods," he said.

The policy gave free coal for fuel boilers to heat homes and offices to cities north of the Huai River, which divides China into north and south. It was in effect for much of the 1950-1980 period of central planning, and, though discontinued after 1980, it has left a legacy in the north of heavy coal burning, which releases particulate pollutants into the air that can harm human health. Researchers found no other government policies that treated China's north differently from the south.

The researchers collected data for 90 cities, from 1981 to 2000, on the annual daily average concentration of total suspended particulates. In China, those are considered to be particles that are 100 micrometers or less in diameter, emitted from sources including power stations, construction sites and vehicles.

The researchers estimated the impact on life expectancies using mortality data from 1991-2000. They found that in the north, the concentration of particulates was 184 micrograms per cubic meter — or 55 percent — higher than in the south, and life expectancies were 5.5 years lower on average across all age ranges.

The researchers said the difference in life expectancies was almost entirely due to an increased incidence of deaths classified as cardiorespiratory — those from causes that have previously been linked to air quality, including heart disease, stroke, lung cancer and respiratory illnesses.

Total suspended particulates include fine particulate matter called PM2.5 — particles with diameters of no more than 2.5 micrometers. PM2.5 is of especially great health concern because it can penetrate deep into the lungs, but the researchers lacked the data to analyze those tiny particles separately.

The authors said their research can be used to estimate the effect of total suspended particulates on other countries and time periods. Their analysis suggests that every additional 100 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter in the atmosphere lowers life expectancy at birth by about three years.

The study also noted that there was a large difference in particulate matter between the north and south, but not in other forms of air pollution such as sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxide.

Francesca Dominici, a professor of biostatistics at Harvard School of Public Health who has researched the health effects of fine particulate matter in the U.S., said the study was "fascinating."

China's different treatment of north and south allowed researchers to get pollution data that would be impossible in a scientific setting.

Dominici said the quasi-experimental approach was a good approximation of a randomized experiment, "especially in this situation where a randomized experiment is not possible."

She said she wasn't surprised by the findings, given China's high levels of pollution.

"In the U.S. I think it's pretty much been accepted that even small changes in PM2.5, much, much, much smaller than what they are observing in China, are affecting life expectancy," said Dominici, who was not involved in the study.

(Also covered by WSJ, WaPo, NYT, AP, Reuters, Bloomberg, LA Times, Nat Geo, Nature, Discover, CNN, CBS, CNBC, PRI, BBC, Guardian, Sky News, International Business Times, Financial Times, The Telegraph, Daily Mail, China.org)

New quasi-experimental research finds major impact of coal emissions on health.

By: Peter Dizikes

A high level of air pollution, in the form of particulates produced by burning coal, significantly shortens the lives of people exposed to it, according to a unique new study of China co-authored by an MIT economist.

The research is based on long-term data compiled for the first time, and projects that the 500 million Chinese who live north of the Huai River are set to lose an aggregate 2.5 billion years of life expectancy due to the extensive use of coal to power boilers for heating throughout the region. Using a quasi-experimental method, the researchers found very different life-expectancy figures for an otherwise similar population south of the Huai River, where government policies were less supportive of coal-powered heating.

“We can now say with more confidence that long-run exposure to pollution, especially particulates, has dramatic consequences for life expectancy,” says Michael Greenstone, the 3M Professor of Environmental Economics at MIT, who conducted the research with colleagues in China and Israel.

The paper, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also contains a generalized metric that can apply to any country’s environment: Every additional 100 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter in the atmosphere lowers life expectancy at birth by three years.

In China, particulate-matter levels were more than 400 micrograms per cubic meter between 1981 and 2001, according to Chinese government agencies; state media have reported even higher levels recently, with cities including Beijing recording levels of more than 700 micrograms per cubic meter in January. (By comparison, total suspended particulates in the United States were about 45 micrograms per cubic meter in the 1990s.)

Air pollution has become an increasingly charged political issue in China, spurring public protests; last month, China’s government announced its intent to adopt a series of measures to limit air pollution.

“Everyone understands it’s unpleasant to be in a polluted place,” Greenstone says. “But to be able to say with some precision what the health costs are, and what the loss of life expectancy is, puts a finer point on the importance of finding policies that balance growth with environmental quality.”

A river runs through it

The research stems from a policy China implemented during its era of central planning, prior to 1980. The Chinese government provided free coal for fuel boilers for all people living north of the Huai River, which has long been used as a rough dividing line between north and south in China.

The free-coal policy means people in the north stay warm in winter — but at the cost of notably worse environmental conditions. Using data covering an unusually long timespan — from 1981 through 2000 — the researchers found that air pollution, as measured by total suspended particulates, was about 55 percent higher north of the river than south of it, for a difference of around 184 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter.

Linking the Chinese pollution data to mortality statistics from 1991 to 2000, the researchers found a sharp difference in mortality rates on either side of the border formed by the Huai River. They also found the variation to be attributable to cardiorespiratory illness, and not to other causes of death.

“It’s not that the Chinese government set out to cause this,” Greenstone says. “This was the unintended consequence of a policy that must have appeared quite sensible.” He notes that China has not generally required installation of equipment to abate air pollution from coal use in homes.

Nonetheless, he observes, by seizing on the policy’s arbitrary use of the Huai River as a boundary, the researchers could approximate a scientific experiment.

“We will never, thank goodness, have a randomized controlled trial where we expose some people to more pollution and other people to less pollution over the course of their lifetimes,” Greenstone says. For that reason, conducting a “quasi-experiment” using existing data is the most precise way to assess such issues.

In their paper, the researchers address some other potential caveats. For instance, extensive mobility in a population might make it hard to draw cause-and-effect conclusions about the health effects of regional pollution. But significantly, in China, Greenstone says, “In this period, migration was quite limited. If someone is in one place, the odds are high they [had always] lived there, and they would have been exposed to the pollution there.”

Moreover, Greenstone adds, “There are no other policies that are different north or south of the river, so far as we could tell.” For that matter, other kinds of air pollution, such as sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxides, are spread similarly north and south of the river. Therefore, it appears that exposure to particulates is the specific cause of reduced life expectancy north of the Huai River.

In addition to Greenstone, the paper has three other co-first authors: Yuyu Chen, of the Guanghua School of Management at Peking University; Avraham Ebenstein, of Hebrew University of Jerusalem; and Hongbin Li, of the School of Economics and Management at Tsinghua University. The research project received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Another reason to limit emissions

Scholars say the paper is an important contribution to its field. Arden Pope, an economist at Brigham Young University and a leading researcher in environmental economics and air pollution, calls it “one of the most dramatic and interesting quasi-experimental studies on the health effects of air pollution that has been conducted.” At the same time, Pope observes, the results are “reasonably consistent” with other air-pollution research using different study designs.

Pope notes that while many air-pollution studies have occurred in the United States and Europe, “It is important to conduct studies in China and elsewhere where the pollution levels are relatively high.” Going forward, he suggests, it would also be desirable for researchers to look for ways to specifically study the health effects of fine particles, those less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter.

Greenstone notes that the researchers were not sure what result they would find when conducting their study. Still, he says of the finding, “I was surprised by the magnitude, both in terms of [the quantity of] particulates, and in terms of human health.”

Greenstone says he hopes the finding will have a policy impact not only in China, but also in other rapidly growing countries that are increasing their consumption of coal. Moreover, he adds, given the need to limit carbon emissions globally in order to slow climate change, he hopes the data will provide additional impetus for countries to think twice about fossil-fuel consumption.

“What this paper helps reveal is that there may be immediate, local reasons for China and other developing countries to rely less on fossil fuels,” Greenstone says. “The planet’s not going to solve the greenhouse-gas problem without the active participation of China. This might give them a reason to act today.”