It’s a challenge to attribute any one storm or heat wave to climate change, but scientists are getting closer. MIT Joint Program Deputy Director C. Adam Schlosser comments in Smithsonian.com.

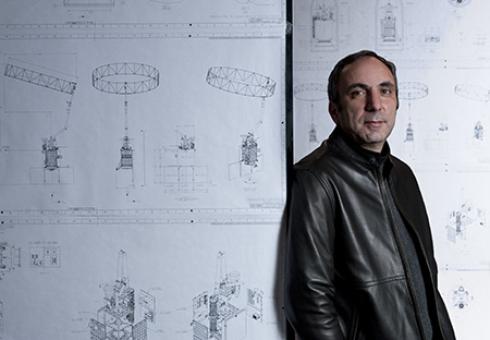

News and Outreach: C. Adam Schlosser

New technique predicts frequency of heavy precipitation with global warming

C. Adam Schlosser assesses long-term risks to regional water and energy systems

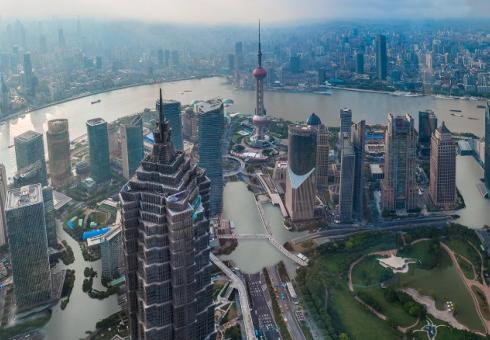

A new study points to the risk that China and India will be facing severe water shortages by 2050 due to a perfect storm of economic growth, climate change, and fast growing populations. Joint Program Deputy Director Adam Schlosser comments on the future of water stress in Asia.

Study finds high risk of severe water stress in Asia by 2050

Includes commentary by John Reilly and climate change calculator based on methodology co-developed by Adam Schlosser

Alli Gold Roberts

MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change

Population growth and increasing social pressures on global water resources have required communities around the globe to focus on the future of water availability. Global climate change is expected to further exacerbate the demands on water-stressed regions. In an effort to assess future water demands and the impacts of climate change, MIT researchers have used a new modeling tool to calculate the ability of global water resources to meet water needs through 2050.

The researchers expect 5 billion (52 percent) of the world’s projected 9.7 billion people to live in water-stressed areas by 2050. They also expect about 1 billion more people to be living in areas where water demand exceeds surface-water supply. A large portion of these regions already face water stress—most notably India, Northern Africa and the Middle East.

The study applies the MIT Integrated Global System Model Water Resource System (IGSM-WRS), a modeling tool with the ability to assess both changing climate and socioeconomics—allowing the researchers to isolate these two influencers. In studying the socioeconomic changes, they find population and economic growth are responsible for most of the increased water stress. Such changes will lead to an additional 1.8 billion people globally living in water-stressed regions.

“Our research highlights the substantial influence of socioeconomic growth on global water resources, potentially worsened by climate change,” says Adam Schlosser, the assistant director of science research at the Joint Program on Global Change and lead author of the study. “Developing nations are expected to face the brunt of these rising water demands, with 80 percent of this additional 1.8 billion living in developing countries.”

Looking at the influence of climate change alone, the researchers find a different result. Climate change will have a greater impact on water resources in developed countries. This is because, for instance, changes in precipitation patterns would limit water supplies needed for irrigation.

When researchers combine the climate and socioeconomic scenarios, a more complicated picture of future water resources emerges. For example, in India, researchers expect to see significant increases in precipitation, contributing to improved water supplies. However, India’s projected population growth and economic development will cause water demands to outstrip surface-water supply.

“There is a growing need for modeling and analysis like this, which takes a comprehensive approach by studying the influence of both climatic and socioeconomic changes and their effects on both supply and demand projections,” says Schlosser. “Our results underscore this need.”

The MIT team plans to continue this work by focusing on specific regions and conducting more detailed analysis of future climate changes and risks to water systems. They plan to refine and add to the model as they research other regions of the globe.

By: Vicki Ekstrom

MIT researchers enhance model to assess the risks of water stress. A conflict over water management has intensified along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Downstream states argue water should be released from the Missouri’s upstream reservoirs into the Mississippi to allow shipping to continue in the record low-level waters. Upstream states are fighting to keep the water to irrigate their crops and prevent the drought from getting even worse next year. To add to the tension, still others want to move a portion of the Missouri River Basin’s water to the Colorado Basin—which will see demand outstrip supply in the coming decades, according to a federal study released last week.

A conflict over water management has intensified along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Downstream states argue water should be released from the Missouri’s upstream reservoirs into the Mississippi to allow shipping to continue in the record low-level waters. Upstream states are fighting to keep the water to irrigate their crops and prevent the drought from getting even worse next year. To add to the tension, still others want to move a portion of the Missouri River Basin’s water to the Colorado Basin—which will see demand outstrip supply in the coming decades, according to a federal study released last week.

These are the stakes in the conflict over water, and the impacts could be profound and widespread. Agriculture, river navigation, energy and other industries all stand to lose as populations increase and the possible side effects of climate change emerge. To measure future changes on water resources, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have enhanced their global model to include a new tool that assesses the risks of water stress.

“As fresh water sources throughout the world experience considerable stress because of an increasing population, economic growth, and droughts, floods and other climate effects, this tool will provide valuable insights to industries and communities competing for water,” says Ken Strzepek, a researcher at the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, who helped design the tool.

Strzepek and his colleagues Adam Schlosser and Élodie Blanc take population, GDP and other socio-economic factors and combine them with hydro-climatic information such as precipitation and runoff from their earth system model. They then combine this information to estimate changes in demand across sectors such as public and private water use, agricultural use and thermoelectric cooling used in energy production. The result is an expanded model that can forecast if and where there could be stresses within water basins, along with the risks surrounding those changes.

“Globally, the tool is helping us see where the hot spots for water stress are and where might that stress increase in the future due to human growth and climate change—two factors that are coming together and exacerbating the problem of water management,” says Schlosser, the assistant director of science research at the Joint Program on Global Change.

While the new model paints the picture globally, it can also be applied at a regional and even local scale to help communities make important decisions about their future energy investments, infrastructure plans and adaptation strategies. Uniquely, by incorporating risk and uncertainty, the model helps policymakers evaluate the question: What investments do we need to make to be better prepared?

“When looking at different climate models, not only do they show different results, they show different directions—one shows a positive change where another might show a negative change,” Schlosser says. “However, our technique allows us to quantify this uncertainty as risk to help decision makers formulate more robust investment plans.”

The researchers have already begun to apply their model to the U.S. While their findings are still being written, the researchers agree that critical water management issues will arise—and in some areas are already emerging. They are finding that the areas that will see the greatest stress going forward are the same places where very rigid water management laws already exist, such as around the Missouri, Mississippi and Colorado rivers.

“Our model framework is able to account for water management and allocation policies,” Schlosser says. “This allows us to take a situation like transferring water from the Missouri to the Colorado Basin and assess the impacts to both basins going forward.”

Drawing from this measure of risk, the researchers warn that decision makers in developing countries should make their adaptation plans both flexible and efficient.

“If we don’t know how much water will come down the river, we should design dams to be constructed in stages. For example, we should make provisions to add hydropower generation capacity easily and accordingly. ” Strzepek says. “We need to have flexible designs, and also efficient designs, so we’re building in a way that the structure will perform well under a variety of climates.”

Read more about the new tool here.