Study tracks pollution from state to state in the 48 contiguous United States

News and Outreach: Steven Barrett

Joint Program researchers call for ongoing investigation of, stricter controls on U.S. cross-state air pollution (The Conversation) (Republished in Salon)

MIT team found that air quality impacts of aviation emissions significantly exceed climate impacts (Coverage: CNN)

TILclimate (Today I Learned: Climate) podcast demystifies the science, technology, and policy surrounding climate change in 10-minute bites

Real-word driving produces up to 16 times more emissions, causing 2,700 premature deaths across the EU, researchers estimate

Study showed long-lasting health, economic impacts of lead emissions from U.S. general aviation flights

Paper: Philip J. Wolfe, Amanda Giang, Akshay Ashok, Noelle E. Selin, and Steven R. H. Barrett. Costs of IQ Loss from Leaded Aviation Gasoline Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2016, 50 (17), 9026–9033. dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02910.

Countries hit hardest by automaker’s emissions scandal include Germany, Poland, France, and Czech Republic

Steven Barrett probes the environmental impact of aviation and options for reducing it

Timely vehicle recall by German automaker would avoid some 130 early deaths, researchers say.

Jennifer Chu | MIT News Office

Volkswagen’s use of software to evade emissions standards in more than 482,000 diesel vehicles sold in the U.S. will directly contribute to 60 premature deaths across the country, a new MIT-led study finds.

In September, the Environmental Protection Agency discovered that the German automaker had developed and installed “defeat devices” (actually software) in light-duty diesel vehicles sold between 2008 and 2015. This software was designed to sense when a car was undergoing an emissions test, and only then engage the vehicle’s full emissions-control system, which would otherwise be disabled under normal driving conditions — a cheat that allows the vehicles to emit 40 times more emissions than permitted by the Clean Air Act.

That amount of excess pollution, multiplied by the number of affected vehicles sold in the U.S. and extrapolated over population distributions and health risk factors across the country, will have significant effects on public health, the study finds.

Assessing health outcomes

According to the study, conducted by researchers at MIT and Harvard University and published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, excess emissions from Volkswagen’s defeat devices will cause around 60 people in the U.S. to die 10 to 20 years prematurely. If the automaker recalls every affected vehicle by the end of 2016, more than 130 additional early deaths may be avoided. If, however, Volkswagen does not order a recall in the U.S., the excess emissions, compounding in the future, will cause 140 people to die early.

In addition to the increase in premature deaths, the researchers estimate that Volkswagen’s excess emissions will contribute directly to 31 cases of chronic bronchitis and 34 hospital admissions involving respiratory and cardiac conditions. They calculate that individuals will experience about 120,000 minor restricted activity days, including work absences, and about 210,000 lower-respiratory symptom days.

In total, Volkswagen’s excess emissions will generate $450 million in health expenses and other social costs, the study projects. But a total vehicle recall by the end of 2016 may save up to $840 million in further health and social costs.

Steven Barrett, the lead author of the paper and an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT, says the new data may help regulatory officials better estimate the effects of Volkswagen’s actions.

“It seemed to be an important issue in which we could bring to bear impartial information to help quantify the human implications of the Volkswagen emissions issue,” Barrett says. “The main motivation is to inform the public and inform the developing regulatory situation.”

Cheating (and) death

To estimate the health effects of Volkswagen’s excess emissions, Barrett and his colleagues at MIT and Harvard based their calculations on measurements by researchers at West Virginia University, who found that the vehicles produced up to 40 times the emissions allowed by law. They then calculated the average amount that each vehicle would be driven over its lifetime, and combined these results with sales data between 2008 and 2015 to estimate of the total excess emissions during this period.

The group then calculated the resulting emissions under three scenarios: the current scenario, in which 482,000 vehicles have already emitted excess emissions into the atmosphere; a scenario in which Volkswagen recalls every affected vehicle by the end of 2016; and a future in which there is no recall, and every affected vehicle remains on the road, continuing to emit excess pollution over the course of its lifetime.

The group then estimated the health effects under each emissions scenario, using a method they developed to map emissions estimates to public exposure to fine particulate matter and ozone. Diesel vehicles emit nitrogen oxides, which react in the atmosphere to form fine particulate matter and ozone. Barrett’s approach essentially maps emissions estimates to population health risk, accounting for atmospheric transport and chemistry of the pollutants.

“We all have risk factors in our lives, and [excess emissions] is another small risk factor,” Barrett explains. “If you take into account the additional risk due to the excess Volkswagen emissions, then roughly 60 people have died or will die early, and on average, a decade or more early.”

Barrett says that, per kilometer driven, this number is about 20 percent of the number of deaths caused by road transport accidents.

“So it’s about the same order of magnitude, just from these excess emissions,” Barrett says. “If nothing’s done, these excess emissions will cause around another 140 deaths. However, two-thirds of the total deaths could be avoided if the recalls could be done quickly, in the course of the next year.”

Daniel Kammen, the editor-in-chief of Environmental Research Letters and a professor of energy at the University of California at Berkeley, says the group’s study provides a “rigorous evaluation of the scale of the impacts, which are potentially exceedingly serious.

“The analysis demonstrates the value of policy-inspired fundamental research where the air quality and health impacts of transgressions such as the VW issue can be calculated, and made available for public discussion,” says Kammen, who did not contribute to the research.

Photo: Workers inspect a car on the production line in a Volkswagen factory in Poznan, Poland

Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

Researchers from MIT’s Laboratory for Aviation and the Environment have come out with some sobering new data on air pollution’s impact on Americans’ health.

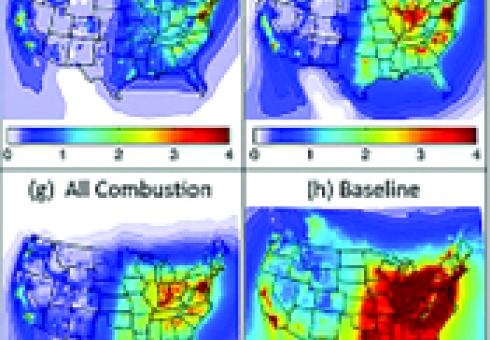

The group tracked ground-level emissions from sources such as industrial smokestacks, vehicle tailpipes, marine and rail operations, and commercial and residential heating throughout the United States, and found that such air pollution causes about 200,000 early deaths each year. Emissions from road transportation are the most significant contributor, causing 53,000 premature deaths, followed closely by power generation, with 52,000.

In a state-by-state analysis, the researchers found that California suffers the worst health impacts from air pollution, with about 21,000 early deaths annually, mostly attributed to road transportation and to commercial and residential emissions from heating and cooking.

The researchers also mapped local emissions in 5,695 U.S. cities, finding the highest emissions-related mortality rate in Baltimore, where 130 out of every 100,000 residents likely die in a given year due to long-term exposure to air pollution.

“In the past five to 10 years, the evidence linking air-pollution exposure to risk of early death has really solidified and gained scientific and political traction,” says Steven Barrett, an assistant professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT. “There’s a realization that air pollution is a major problem in any city, and there’s a desire to do something about it.”

Barrett and his colleagues have published their results in the journal Atmospheric Environment.

Data divided

Barrett says that a person who dies from an air pollution-related cause typically dies about a decade earlier than he or she otherwise might have. To determine the number of early deaths from air pollution, the team first obtained emissions data from the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Emissions Inventory, a catalog of emissions sources nationwide. The researchers collected data from the year 2005, the most recent data available at the time of the study.

They then divided the data into six emissions sectors: electric power generation; industry; commercial and residential sources; road transportation; marine transportation; and rail transportation. Barrett’s team fed the emissions data from all six sources into an air-quality simulation of the impact of emissions on particles and gases in the atmosphere.

To see where emissions had the greatest impact, they removed each sector of interest from the simulation and observed the difference in pollutant concentrations. The team then overlaid the resulting pollutant data on population-density maps of the United States to observe which populations were most exposed to pollution from each source.

Health impacts sector by sector

The greatest number of emissions-related premature deaths came from road transportation, with 53,000 early deaths per year attributed to exhaust from the tailpipes of cars and trucks.

“It was surprising to me just how significant road transportation was,” Barrett observes, “especially when you imagine [that] coal-fired power stations are burning relatively dirty fuel.”

One explanation may be that vehicles tend to travel in populated areas, increasing large populations’ pollution exposure, whereas power plants are generally located far from most populations and their emissions are deposited at a higher altitude.

Pollution from electricity generation still accounted for 52,000 premature deaths annually. The largest impact was seen in the east-central United States and in the Midwest: Eastern power plants tend to use coal with higher sulfur content than Western plants.

Unsurprisingly, most premature deaths due to commercial and residential pollution sources, such as heating and cooking emissions, occurred in densely populated regions along the East and West coasts. Pollution from industrial activities was highest in the Midwest, roughly between Chicago and Detroit, as well as around Philadelphia, Atlanta and Los Angeles. Industrial emissions also peaked along the Gulf Coast region, possibly due to the proximity of the largest oil refineries in the United States.

Southern California saw the largest health impact from marine-derived pollution, such as from shipping and port activities, with 3,500 related early deaths. Emissions-related deaths from rail activities were comparatively slight, and spread uniformly across the east-central part of the country and the Midwest.