News + Media

MIT researchers, using field practices, find emissions from shale gas production to be significantly lower than previous estimates.

While the United States lags in developing a broad-based climate policy, the nation’s carbon emissions reached a 20-year low this year. Many have attributed some of that drop to a booming supply of low-carbon natural gas, of which the United States is the world’s largest producer. But does natural gas – and specifically the quickly-developing production of shale gas – create other emissions, such as methane, that could be just as harmful? A new study by MIT researchers shows the amount of methane emissions caused by shale gas production has been largely exaggerated.

“While increased efforts need to be made to reduce emissions from the gas industry overall, the production of shale gas has not significantly increased total emissions from the sector,” says Francis O’Sullivan, a researcher at the MIT Energy Initiative and the lead author of the study released this week in Environmental Research Letters.

The research comes amidst several other reports on the impact of “fugitive” methane emissions – gas leaked or purposefully vented during and immediately after the stage of shale gas production known as hydraulic fracturing. While many of these reports studied the amount of potential emissions associated with the hydraulic fracturing process, the MIT researchers stress that this is only part of the puzzle. Consideration must also be given to how this gas is handled at the drilling sites, the study shows.

“It’s unrealistic to assume all potential emissions are vented,” O’Sullivan says, “Not least because some states have regulations requiring flaring as a minimum gas handling method.”

Sergey Paltsev, the study’s co-author and the assistant director for economic research at the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, says companies also have an economic reason for wanting to capture this “fugitive” gas.

“When companies vent and flare methane they are losing gas that they could have captured and sold” Paltsev says. “When we compared the cost of installing the right equipment to capture this gas to the loss in revenue if it isn’t captured, we found that the majority of shale wells make money by capturing the potential ‘fugitive’ emissions.”

In talking with industry representatives and officials at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), O’Sullivan and Paltsev found that companies are already capturing about 70 percent of potential “fugitive” emissions. In factoring that into their analysis, the researchers find emissions from shale gas production to be strikingly lower than previous estimates of potential emissions.

Their analysis was based on data from each of the approximately 4,000 wells drilled in the five main U.S. shale drilling sites during 2010. Wells in two of those sites, Texas’ Barnett shale and the Haynesville shale on the Texas-Louisiana boarder, had been studied by Robert Howarth from Cornell University last year when he looked at potential emissions released by the industry. His study garnered much attention because it claimed the greenhouse gas footprint of shale gas was larger than that of conventional gas, oil, and, over a 20-year time frame, coal. That study, however, used very limited well datasets.

In studying potential emissions, Howarth found 252 Mg of methane emissions per well in the Barnett site and 4,638 Mg per well in the Haynesville site. The MIT researchers, using their comprehensive well dataset, found that the potential emissions per well in the Barnett and Haynesville sites were in fact 147 Mg of methane (273 thousand cubic meters of natural gas) and 633 Mg (1,177 thousand cublic meters of gas), respectively. When accounting for actual gas handling field practices, these emissions estimates were reduced to about 35 Mg per well of methane from an average Barnett well and 151 Mg from an average Haynesville well.

According to Adam Brandt, an assistant professor at Stanford University, this analysis “provides an important contribution to the literature by greatly improving our understanding of potential shale gas emissions using a very large dataset.”

Brandt says, “Previous studies used much smaller and more uncertain datasets, while O'Sullivan and Paltsev have gathered a much larger and more comprehensive industry dataset. This significantly reduces the uncertainty associated with potential emissions from shale gas development.”

A U.S. Department of Energy study released in August confirmed that while electricity generated by gas produces half the emissions of coal generation, natural gas production does make up 3 percent of the nation’s total emissions. While the overall benefits far outweigh the small increases during production, Paltsev believes the EPA’s efforts to reduce those emissions through new air quality standards are a “step in the right direction.”

Read an op-ed by MIT researchers in response to the Howarth study here.

Watching the Arctic Melt: Adventures in Polar Oceanography

by Genevieve Wanucha

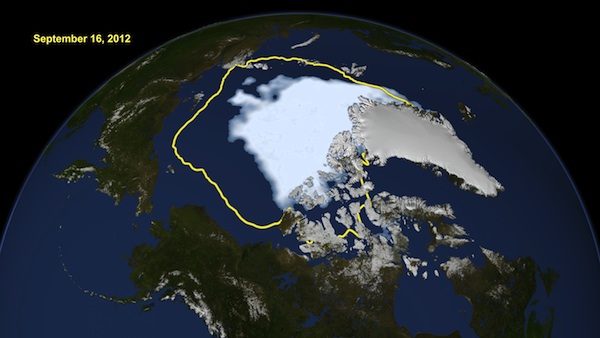

One hundred people packed into the Whitehead Institute on November 19th to attend the Oceans at MIT special symposium, entitled ‘Watching the Arctic Melt: Adventures in Polar Oceanography.’ Most people there already knew that the Arctic Ocean’s ice cover goes through a cycle of seasonal growth and decline. Everyone had already heard that the Arctic Ocean sea ice cover hit a record minimum this fall. More surprising was the news that the Arctic, which has warmed twice the global average, may experience ice-free summers before 2050.

WHOI’s Hanu Singh suprises the audience with stunning images of an autonomous underwater vehicle. Singh and his lab members send these robots down through holes in Arctic sea ice to explore the underside of sea ice.

“This melting has enormous implications for shipping, fishing, Arctic ecology, oil and gas exploration, national security, and geopolitics,” said John Marshall, professor of oceanography at MIT, who kicked off the afternoon. “There is likely to be a ‘Gold Rush’ as the oil and gas resources in the Arctic become more available as it thaws.”

The event was a quintessential example of the close and longstanding collaboration between MIT and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, bringing together Arctic experts who are all pushing technical frontiers to study the high-stakes Arctic ice loss.

Their ultimate goal, as it soon became clear, is to be able to predict and model the behavior of the Arctic melting. However, that’s far from straightforward. As Patrick Heimbach, a principal research scientist in EAPS, emphasized, scientific prediction requires understanding—an understanding of, for instance, how ice sheets break apart and how ice interacts with the warming air above and water below. And understanding requires observation.

Fortunately, these speakers are bringing observation in the Arctic to the next level, especially John Toole, a senior scientist and chair of physical oceanography at WHOI who studies how the shrinking ice cap affects Arctic Ocean circulation. “Satellite data is useful, but it’s only skin deep,” he said as he took the stage. “It doesn’t give you information about the ocean interior.” So, he’s created tools to figure out what goes on below the ice.

Toole’s innovation, the “ice-tethered profiler,” is a buoy that sits atop the ice sheet, sending a wire down through the ice. A vehicle crawls up and down the wire, sending high-resolution data up to a satellite. His team has deployed 60 profilers since 2004 and will launch more next year. The huge amounts of data the profilers collect are allowing any researcher to track seasonal patterns in Arctic through measures of salinity, oxygen, water velocity, and photosynthetic radiation.

Satellite image of the new record low Arctic sea ice extent, from Sept. 16, 2012, compared to the average minimum extent over the past 30 years (in yellow). Credit: Credit: NASA/Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio

Art Baggeroer and Henrik Schmidt, both professors at MIT’s Ocean Seismo-Acoustic Laboratory MIT, reported on their efforts to observe the Arctic using sound. By recording the sound and seismic waves traveling in the Arctic Ocean, they can infer exactly how and why the sea ice is breaking up.

Carin Ashjian, a senior scientist in the biology department at WHOI, uses a range of acoustic and video methods to study the surprisingly active ecosystem alive under the ice sheet. She’s spent day traveling aboard icebreakers in harsh weather to collect data on zooplankton, the preferred food of Arctic fish and whales, in hopes of modeling how temperature changes will lower their reproductive success. One big issue stand in her way.

“We don’t have a whole lot of long term records, and this makes it difficult to detect changes in the ecosystem,” she pointed out. “We need to continue our ongoing efforts to understand the natural variability of the Arctic so we can detect change.”

Admiral Richard Pittenger (Ret.), former leader of WHOI’s Marine Operations Division, suggested that the US Navy will be central to providing the infrastructure for this research effort, more for national security reasons than the ecosystem. It’s been a long road to acceptance of climate change within government institutions, but, he noted, “The Navy is one hundred percent on board. They know there are many strategic disadvantages if we aren’t preparing for the effects.”

Perhaps the most memorable moment of the afternoon came when WHOI’s Hanu Singh and MIT’s John Leonard revealed video of robotic vehicle swimming through icy blue water, mapping the moving Arctic Ocean sea ice and floor. The audience now saw what scientists see in this footage: not beautiful, exciting images of adventure, but a glimpse at the first, slow steps in one of the most challenging research endeavors of our time.

MIT Researcher Receives Award for Forecasts of Vehicle Use in China

Paul Kishimoto, a research associate for the MIT Joint Program’s China Energy and Climate Project, was one of five winners of the Dennis J. O'Brian Student Paper Award sponsored by the U.S. Association of Energy Economics on November 6. His study, “Applying Advanced Uncertainty Methods to Improve Forecasts of Vehicle Ownership and Passenger Travel in China,” analyzes the uncertainty of China’s transportation sector.

“This paper grew from work I did for a graduate course in uncertainty, which included methods like those used to generate the Joint Program's Greenhouse Gamble wheels,” says Kishimoto, a recent graduate of MIT’s Technology and Policy Program (TPP). “I think the judges recognized that the application to transportation was novel, and as a result I was able to attend a very engaging conference.”

China is home to the world’s largest vehicle market – a market that is increasing each day because of the country’s growing, wealthier population. Annual vehicle sales in China have grown by as much as 38 percent a year – a pace unmatched by any other country. China is also deeply reliant on foreign oil. In 2011, the country imported more than 60 percent of the oil it consumed. Along with this growth and reliance comes much uncertainty: How accurate are the statistics coming from the Chinese government? What policies will the central and local governments put in place to restrict vehicle use, subsidize alternate fuel vehicles, or redirect demand to public transit? What path will the economic expansion take, and how will this affect households' travel?

Using a Monte-Carlo sampling method to evaluate uncertainty, Kishimoto lays out a range of vehicle ownership and travel volume forecasts. These forecasts could be used to successfully plan and manage large transport infrastructure projects in China. In the average forecast, four out of every ten people could own vehicles in 2050. But this outcome is highly uncertain. On the other hand, a more certain forecast shows that there could be an eventual peak of about six out of every ten people owning vehicles. Shares of different transport modes show narrower ranges, in which urban and inter-city rail continues to supply at least 26 percent of passenger miles.

“These results are a useful counterpoint to our modeling using the MIT EPPA model. They show, given recent trends, how Chinese people might prefer to travel in the future,” says Kishimoto. “With EPPA, we can model how government policy, increases in fuel prices due to high demand, and other effects will alter these choices and the related energy use and emissions.”

Kishimoto was presented with the award at the International Association of Energy Economics’ Annual North American Conference in Austin, Texas.

This week, a reinvigorated Barack Obama returned to the White House knowing that he was poised on the edge of a fiscal cliff. Rather than relishing his victory last week, Obama must immediately set about crafting a compromise on deficit reduction with congressional leaders. The stakes could hardly be higher — for science, for US citizens and, indeed, for the world. In the event of failure, a budgetary time-bomb of tax increases and sweeping budget cuts will detonate on 2 January. As well as resulting in indiscriminate cuts to funds for scientific research and many other areas, it could knock the United States back into recession and deliver yet another blow to an already fragile global economy.

Faced with such dire consequences, one might expect that all the financial options would be on the table, especially the good ones. Unfortunately, this is not the case, at least not yet.

So far, lawmakers have rehashed long-standing disputes about the size of government and the social safety net, but have ignored ideas that could transform the fiscal challenge into an opportunity. One such proposal is the carbon tax, which could bring financial and political benefits for all and chart a new course forward for energy independence and global warming (see page 309). It is a solution that is every bit as improbable as it is logical, but one should remember Winston Churchill’s assessment of the United States’ tendency to do the right thing — once all the alternatives have been exhausted.

Just consider the possibilities. To put a levy on carbon would raise revenues that could be used to offset lower tax rates for individuals and businesses. This is what conservatives say they want to do. It would put more income — and thus choice — in the hands of consumers. Economists like the idea for more fundamental reasons. Generally, it is best to tax things that one wishes to discourage (such as smoking) rather than those that should be encouraged (such as working). Environmentalists like the idea of a carbon tax because it could generate some much-needed revenue for clean-energy research and development while reducing carbon emissions.

The numbers are not negligible. An analysis conducted in August by economists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge showed that a carbon tax of US$20 per tonne of carbon from fossil fuels, if instituted in 2013 and increased by 4% per year, would raise $1.5 trillion over the course of a decade. Averaged out, this amounts to $150 billion annually — a sizeable chunk of the trillion-dollar deficits that the US government has been running in recent years. Scholars at the Brookings Institution, a centrist think tank in Washington DC, advocate ramping federal investments in energy research up from $3.8 billion now to $30 billion annually, to drive down the cost of low-carbon energy (including cleaner-burning coal). It is an ambitious proposal, and would leave a pile of cash that could be redistributed elsewhere for beneficial use.

Conservatives loathe taxes, and US politicians obsess over energy prices, but a revenue-neutral carbon tax would get around these problems. The MIT analysis found that the economy benefited regardless of whether the money was reinvested in social programmes or redistributed in the form of lower taxes and cash payments to offset higher energy costs for the poor. For environmentalists, the problem with a carbon tax is that it does not technically limit emissions, but the MIT model suggests that it would perform quite well: carbon emissions fall to 14% below 2006 levels by 2020 as consumers and businesses find ways to reduce their energy use in response to higher prices.

Opposition to the idea may not be what it was. For example, on 13 November, the American Enterprise Institute hosted a conference in Washington DC on the economics of a carbon tax. The institute is a conservative think tank, and its officials have previously raised doubts about climate science. The idea has also been bubbling up in other right-leaning think tanks as a conservative solution to reduce greenhouse gases.

The problem is that to enact a carbon tax would depend on political courage and a willingness to break with party orthodoxy, rare traits in Washington today. President Obama has made energy and climate part of his agenda for the second term, but his first — and perhaps biggest — opportunity to make good on that promise will come in the next few weeks. As US politicians contemplate diving into the fiscal abyss, they would be wise to consider a painless policy that benefits everyone.

By Keith Johnson

With the fiscal cliff looming and parts of the U.S. still digging out from the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, calls for the U.S. to adopt a carbon tax are gathering steam–even though there’s little sign of interest from Congress or the White House.

Today the conservative American Enterprise Institute is holding an all-day, on-the-record discussion of the idea. And the Brookings Institution is unveiling a slate of new measures meant to make the government more effective, including a carbon tax that could raise $1.5 trillion over ten years. All that follows a cascade of carbon-tax advocacy in recent days from the chattering classes and a slate of academic work over the summer (not to mention our own two cents).

The idea of a carbon tax is simple: Put a price tag on the harmful emissions from fossil fuels, such as oil and coal, and use the revenues to fund clean-energy development, pay down the deficit or slash taxes. Proponents often describe it as a win-win-win policy, because carbon taxes would penalize things that are bad (pollution) and lower taxes on things that are good (labor and capital).

“The time seems ripe for this discussion. The president is committed both to raising tax revenue and to dealing with climate change. A carbon tax kills two birds with one stone,” said Gregory Mankiw, a Harvard economist who advised the Romney campaign and has long pushed for more efficient taxation, including a carbon tax.

The Brookings proposal would impose a $20 fee on each ton of carbon, raising an average of $150 billion per year over a decade. Congress and the president would have to decide exactly how to use the money. Research by MIT and Brookings suggests that business-related tax breaks, whether corporate taxes or taxes on investment, would provide the biggest boost to economic growth and job creation.

But at least $30 billion a year should be earmarked for energy research and development, says Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program. That’s because even a price on carbon emissions would not automatically make low-carbon energy such as wind, solar, geothermal and the like economically competitive with traditional fuels. Some research indicates that a $20 carbon tax would actually amount to less support for clean energy than the existing panoply of tax breaks and subsidies.

Alas for the wonks, a carbon tax is a new tax, and that isn’t a popular idea in Washington. Opponents of carbon taxes are rolling out their own intellectual artillery, arguing that the tax would stunt economic growth for little benefit. Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform, said taxing energy consumption “would inevitably lead to higher taxes … even if originally passed with offsetting tax reductions elsewhere.”

Even one-time proponents of a carbon tax in Congress have disavowed the idea. While President Barack Obama mentioned climate change in his victory speech last week and has let the Environmental Protection Agency clamp down on emissions from coal-fired power plants, he has yet to outline any comprehensive plan to tackle climate change in his second term.

The carbon-tax crowd is a big tent, bringing together deficit hawks, growth mavens and climate worriers. The ideological diversity could be a plus–but only if advocates can leverage it to win political support from both sides of the spectrum.

MIT researchers show merits of a carbon tax. New standards to strengthen vehicle fuel efficiency are considered one of the landmark environmental achievements of President Obama’s first term. Passed with the backing of automakers and autoworkers, the measure has been touted as a way to save consumers more than $1.7 trillion at the pump and cut carbon emissions from passenger vehicles in half. While the standards have many good merits, a more effective approach might be an economy-wide carbon tax, say researchers at MIT’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.

New standards to strengthen vehicle fuel efficiency are considered one of the landmark environmental achievements of President Obama’s first term. Passed with the backing of automakers and autoworkers, the measure has been touted as a way to save consumers more than $1.7 trillion at the pump and cut carbon emissions from passenger vehicles in half. While the standards have many good merits, a more effective approach might be an economy-wide carbon tax, say researchers at MIT’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.

The researchers look at the full energy and economic impacts of the efficiency standards, which in their finalized form now require automakers to install pollution-control technology to improve the fuel efficiency of cars by 5 percent and light trucks by 3.5 percent with each new model year starting in 2017. Published this month in the journal Transportation Research Record, the study won this year’s Pyke Johnson Award for the best paper in the area of planning and the environment.

“Common thinking in Washington holds that any policy that seems to advance technology without creating new taxes must be a no brainer for the country. That misses the broader economic impact,” says Joint Program Research Scientist Valerie Karplus, the lead author of the study. “As my colleague says, you may see more money in your front pocket at the pump, but you’re financing the policy out of your back pocket through your tax dollars and at the point of your vehicle purchase.”

Instead, Karplus says a gasoline or carbon tax makes more sense economically by providing consumers a direct incentive to either reduce their driving or buy more efficient vehicles.

“From an economic perspective that’s very clear, but from a political feasibility perspective it’s very different,” she says. Unlike fuel standards that hide the true costs, “a tax on gasoline has proven to be a nonstarter for many decades in the U.S., and I think one of the reasons is that it would be very visible to consumers every time they go to fill up their cars.”

The one hope, Karplus and some of her colleagues at the Joint Program say, is that in the midst of deficit talks a tax on carbon emissions might be considered to help raise the money needed to slash the deficit and avoid some tax hikes and spending cuts. The program published a study in August that looked at the effectiveness of this approach. That study showed that with a carbon tax the economy could overall improve, other taxes could be lowered and pollution emissions would be reduced.

“Congress will face many difficult tradeoffs in stimulating the economy and job growth while reducing the deficit,” says John Reilly, the co-director of the Joint Program and an author of the carbon tax study. “But with the carbon tax there are virtually no serious tradeoffs.”

Conversely, when Karplus and her colleagues simulated the proposed fuel economy standards, they found that while drivers of these more efficient vehicles will likely save at the pump, they could on average spend several thousands of dollars more when buying their new car, consistent with EPA estimates. Even more troubling, diverting efforts toward improved vehicle efficiency distorts overall economic activity, adding to the indirect cost of the policy.

Estimates of how costly the policy would be — in terms of both direct costs to consumers and the larger rippling costs to the economy — hinge on the relative cost of the technology and other strategies available to improve efficiency. The shorter the time frame automakers have to develop the technology and produce more efficient vehicles, the less time there will be for technological progress and other factors to drive down costs — such as the cost of batteries — and the more consumers will need to pay upfront. Emissions and oil imports will initially drop, both due to increased fuel efficiency and as the higher vehicle costs weigh on consumer budgets. But as consumers face lower costs per mile traveled, they may drive more, offsetting reductions in emissions and oil imports.

Karplus hopes her results will help policymakers make more informed decisions going forward. She credits that to the innovative — and award-winning — method she used, which weaves engineering and technology constraints into a broad economic framework and allows researchers to test the cost and other impacts of a policy at different levels of stringency. This method inherently takes account of life-cycle emissions as well as impacts that transmit across fuel markets by affecting prices.

For example, a policy might only consider gasoline use by plug-in electric hybrids. But that “tailpipe measure” doesn’t take into account the emissions created from building, transporting and recharging those batteries. Her approach does.

“There are a lot of hidden costs to a policy like this,” Karplus says. “This model doesn’t allow you to ignore other important aspects of the economy and energy systems. It requires you to be explicit about your technology and cost assumptions. It provides a framework that allows lawmakers to look at all the available information on costs and the state of the technology and decide how to best create or update policies.”

Of this approach, University of Maine environmental economist Jonathan Rubin, says “The research of Dr. Karplus on the energy and climate impacts of the nation’s fuel economy standards for our cars and trucks makes an important contribution to policymaking based on science.”

Rubin is the chair of the Transportation Energy Committee of the Transportation Research Board, which will honor Karplus with the Pyke Johnson award at a ceremony in January.

By: Dylan Matthews

Grover Norquist made headlines Monday night for saying that while he thinks a “carbon tax swap” — in which such a tax finances cuts to the income tax — is bad policy, he doesn’t think it violates his anti-tax pledge. This isn’t as big a deal as you might think, not least because the chances of a carbon tax were always slim, but it does raise the question: What would a carbon tax swap actually look like?

A paper in August by MIT’s Sebastian Rausch and John M. Reilly — which Brad highlighted upon release — asks how much you could cut various taxes if you imposed a carbon tax, starting at $20 per ton in 2013 and increasing by 4 percent every year thereafter. The answer: not that much.

The first table below shows how much you could cut various taxes if 100 percent of carbon tax revenues are used to finance the cuts. The second table shows potential cuts if only half of the revenue goes to other cuts. The latter scenario seems likelier as part of a deficit reduction deal, as the former would be revenue-neutral and thus do nothing to balance the budget:

In 2015, a 100 percent swap would only allow income tax rates to fall 0.59 percentage points, relative to all the Bush tax cuts expiring. So the top rate would be 39 percent rather than 39.6 percent. That’s hardly a game-changer. The possible income tax cuts are barely perceptible when only half of revenue funds rate reductions.

The situation is a bit more promising for tax and corporate taxes. A full swap would finance a 1.59 point reduction in the payroll tax in 2015, almost as much as the two point cut in place for the past two years. Alternately, it would allow the corporate income tax rate to drop below 33 percent from its current level of 35 percent.

Rausch and Reilly found that cutting the corporate (blue line) or personal (red) income tax as part of a swap would be regressive, but using it to pay for a payroll tax cut (black) or social programs for the poor like Medicaid (green) would be highly progressive. Here’s how each would affect the incomes of people across the income spectrum:

Source: Rausch and Reilly

The Medicaid option is a big boon for people making up to $75,000, and a net tax increase above that point. A payroll tax cut benefits everyone but those making over $150,000, while personal or corporate tax cuts help everyone but the very poor.

Another option, proposed by Gilbert Metcalf, a Tufts economist currently heading up the environmental tax division at Treasury, is using a carbon tax to fund an exemption in the payroll tax. Currently, Social Security taxes apply to the first dollar you earn, until you reach the cap (currently $110,100). Metcalf finds that a $15 per ton carbon tax would allow the government to exempt the first $3,660 a given worker earns from the payroll tax, similar to how personal exemptions allow all income tax payers to exempt the first few thousand dollars they earn.

Metcalf’s plan would be more regressive than the ones Rausch and Reilly looked at. The bottom 30 percent of the income distribution would see taxes increase by as much as 1.1 percent of income, while middle class people would see modest tax cuts and the very rich would be unaffected. That suggests that policymakers concerned with progressivity would do better to use a carbon tax to fund entitlements or a payroll tax rate cut than an exemption.

(The author is a Reuters market analyst. The views expressed are his own.)

By Gerard Wynn

(Reuters) - Academics and lawmakers have proposed a U.S. carbon tax to curb carbon emissions and trim the debt pile, but the idea depends on prominent Republican support, so far absent.

Without a deal on cutting the fiscal deficit the United States faces a $600 billion package of automatic tax increases and spending cuts which could tip the country back into recession.

While that is clearly a step too far, the consensus is that a more gradual combination of spending cuts and/or tax hikes is required to avoid a borrowing crisis.

Many economists have argued for a carbon tax: it would lead to net welfare benefits compared with for example hikes in income tax, even before allowing for avoided climate change.

But it faces formidable problems.

It would acknowledge a climate threat, hike energy prices, hurt U.S. competitiveness (without including complicated compensating measures), and sound very much like a failed cap and trade bill.

To progress, supporters would have to paint a nightmare alternative including cuts in defense and social spending and income tax rises, and demonstrate clear daylight with a proposed cap and trade scheme which failed to win Congress approval in 2009.

Some energy executives and notably Exxon's chief executive have previously said they much prefer a carbon tax.

A cap and trade bill only narrowly passed the House of Representatives by 219-212 in June 2009 before mid-term elections saw Republicans take a House majority, and failed to pass the Senate.

PRICE

A carbon tax, or cap and trade scheme makes emitters pay for climate damage from burning fossil fuels and so drives a shift towards cleaner alternatives.

The notion of using carbon pricing to cut the U.S. budget deficit dates back to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report in March 2011, "Reducing the Deficit: Spending and Revenue Options."

The CBO reviewed cap and trade, or a carbon tax among 104 other options for raising tax revenues or cutting spending.

It reported that a scheme which applied a carbon price of $20 tax per tonne of CO2 would raise nearly $1.2 trillion by 2021.

Costs would be passed to energy consumers, its biggest political problem not always mentioned by economists, requiring some compensation which would steal funds from deficit cutting.

"The government could use some of those revenues to accomplish various goals such as reducing taxes, offsetting the costs of the cap-and-trade programme for certain groups or industries that are put at a competitive disadvantage by the programme, or reducing the federal deficit," the CBO report said.

ECONOMICS

A Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) study in August found that a carbon tax would have a net economic benefit compared with allowing certain Bush-era tax cuts to expire, while still cutting the deficit.

Effectively they would swap one tax (on income, if Bush cuts expire on December 31) for another (on carbon).

The authors attributed the net economic benefit to a greater "drag" on the economy from income tax than a carbon tax.

The study did not quantify other benefits such as avoided climate change or lower crude oil imports, or try to compensate energy consumers.

"Given that all other options for dealing with the Federal deficit require difficult tradeoffs, it would seem hard to pass up one that offers so many advantages," the authors concluded in their paper "Carbon Tax Revenue and the Budget Deficit: A Win-Win-Win Solution?".

As Joseph Stiglitz said, in support of a carbon tax in his 2006 book "Making Globalisation Work":

"The country as a whole might be better off; it can use the revenue from the carbon tax to reduce other taxes, such as those on savings, investment, or work. These lower taxes would stimulate the economy, with benefits far greater than the cost of the carbon tax. This is consistent with a general economic principle: it is better to tax things that are bad like pollution than things that are good like savings or work."

ENERGY

Support from economists is one thing.

Given expected higher fossil fuel energy prices and therefore lower consumption, an endorsement by Exxon Chief Executive Rex Tillerson three years ago was more startling.

But that was in the context of shooting down cap and trade proposals when no alternative tax was suggested, and may therefore be more significant for rejecting one than supporting the other.

"As a businessman it is hard to speak favorably about any new tax. But a carbon tax strikes me as a more direct, a more transparent and a more effective approach (than cap and trade). It could be levied under the current tax code without requiring significant new infrastructure or enforcement bureaucracies," Tillerson told a Washington energy security conference in 2009, as quoted in the Exxon journal "The Lamp".

"A carbon tax is also the most efficient means of reflecting the cost of carbon in all economic decisions - from investments made by companies to fuel their requirements to the product choices made by consumers.

"Such a tax should be made revenue neutral. In other words, the size of government need not increase due to the imposition of a carbon tax. There should be reductions or changes to other taxes - such as income or excise taxes - to offset the impacts of the carbon tax on the economy."

POLITICS

The biggest practical problem of a carbon tax is softening its impact on energy consumers and energy-intensive industries.

The European Union has demonstrated that distribution problems can be solved, where for example power plants in poorer east European countries face a softer transition, and factories which face international competition get free emissions permits.

But political efforts now to raise European carbon prices face opposition from some member states, concerned about higher energy prices, even though it would raise funds for government coffers, in the same way as a U.S. tax.

In the face of undoubted, entrenched opposition from certain stakeholders including energy-intensive manufacturers and farmers, the only chance for a carbon tax in the United States is if Democrats prioritize it, and Republicans accept it as the least-worst option, for environmental legislation.

By: Steven Mufson, November 9

Here’s a riddle: If Congress doesn’t want to raise income tax rates but wants to raise revenue, what can it do?

One answer: Pass a carbon tax.

A relatively moderate-sized carbon tax could raise $1.25 trillion over the next decade, a huge chunk of the money needed to bring the federal budget deficit under control. And the idea is getting a closer look now that the election is over and the “fiscal cliff” is looming.

Because it would tax fossil fuel use, the carbon tax pleases economists who want to encourage investment and discourage consumption. Climate activists hope it would reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by penalizing the use of coal, oil and natural gas. And for lawmakers opposed to any change in tax rates or deep cuts in spending, the carbon tax could be a lifeline.

“In the general scheme of things, taxes discourage whatever you’re taxing,” said William Pizer, associate professor of economic and environmental policy at Duke University. “If something is discouraged, it might as well be something bad like pollution instead of employment and savings.”

Pizer said that a $20-a-ton tax on carbon dioxide would raise gasoline prices by about 20 cents per gallon and boost electric bills slightly. It could be most efficiently collected “upstream,” at coal mines, oil and gas wells, or terminals for oil tankers arriving at U.S. shores.

There are drawbacks. Higher prices fall most heavily on lower-income earners who spend a larger portion of their pay on fuel. The tax would hurt certain regions more than others. It would need to be tweaked to protect firms that export to countries where companies don’t pay any carbon tax. It would also have to be reconciled with existing carbon trading schemes in the Northeast and California.

“Taxation is a painful thing, but this is one of the least inefficient ways of raising taxes,” said Nick Robins, head of the climate change center for banking giant HSBC. “At a time of low economic growth, it can be quite a good thing because it is taking costs out of the economy. If you can do that, it would be a good thing.”

As a matter of negotiating strategy, now might be a bad time for the Obama administration to advertise interest in a carbon tax. Doing so would make it a “lightning rod,” said Pizer, a former Treasury official. But, he added, once people see the pros and cons of other taxes and once they reach an impasse and need more revenues, a carbon tax might be an attractive alternative.

“From a policy-making point of view, it is clear that there is no way that this Congress is going to glom onto a carbon tax as an environmental policy,” said Philip R. Sharp, who served two decades in the House and is now president of Resources for the Future. “But it could become an important enabler for other things the Congress wants to do, namely eliminating the deficit and tax reform.”

In the past, conservatives have supported the idea of a carbon tax, though most of them have opposed using the receipts to swell government coffers.

N. Gregory Mankiw — a Harvard University economics professor, adviser to GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney and former chairman of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers — has long supported a carbon tax because he says the price of fossil fuels doesn’t reflect their true societal costs. In the past, he said he would use the receipts to lower other taxes.

In 2007, Kevin Hassett of the American Enterprise Institute, said a carbon tax would not only help energy security and attack global warming, it could also raise a quarter as much revenue as the corporate income tax and could be used to cut those rates.

In 2009, Exxon Mobil chief executive Rex Tillerson — in part to slow momentum toward a cap-and-trade system for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions — endorsed the carbon tax and said it should be set “somewhere north of” $20 a ton.

“As a businessman it is hard to speak favorably about any new tax. But a carbon tax strikes me as a more direct, a more transparent and a more effective approach,” he said at the time. He added that “a carbon tax is also the most efficient means of reflecting the cost of carbon in all economic decisions — from investments made by companies to fuel their requirements to the product choices made by consumers.”

But he, too, said it should be revenue neutral.

One leading GOP advocate of the carbon tax just flipped position. House member and Sen.-elect Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) co-sponsored a carbon tax bill in 2009. But Friday, a spokesman told The Hill newspaper that Flake “has no plans to reintroduce it or support it as part of a tax reform package.”

The American Petroleum Institute (API) opposes a carbon tax. “Anytime we look at an energy issue, be it a tax or regulatory issue, we ask what does it do to promote or inhibit energy production and what is the impact on the American people,” said Jack Gerard, API president. “Clearly, it would increase costs to the American public. Is that what he [President Obama] wants to do? I would think not.”

But compared to the fiscal cliff , even a carbon tax might look attractive. A study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said “the economy is better off with the carbon tax than if taxes remain high to maintain Federal revenue.”

“We’ve been just surprised at the number of political groups across the political spectrum considering this,” said Sharp of Resources for the Future. “Contrary to what almost everybody universally would have said two years ago, we have gotten ourselves in such a pickle on the fiscal side of things that it opens up the possibility.”

MIT researchers develop tool to assess regional risks of climate change, potential impacts on local infrastructure and planning. Climate scientists cannot attribute any single weather event — whether a drought, wildfire or extreme storm — to climate change. But extreme events, such as Hurricane Sandy, are glimpses of the types of occurrences the world could be more vulnerable to in the future. As the devastation left by Sandy continues to reverberate, decision-makers at every level are asking: How can we be better prepared?

Climate scientists cannot attribute any single weather event — whether a drought, wildfire or extreme storm — to climate change. But extreme events, such as Hurricane Sandy, are glimpses of the types of occurrences the world could be more vulnerable to in the future. As the devastation left by Sandy continues to reverberate, decision-makers at every level are asking: How can we be better prepared?

MIT researchers have developed a new tool to help policymakers, city planners and others see the possible local effects of climate change. Its regional projections of climate trends — such as long-term temperature and precipitation changes — allow local planners to evaluate risks, and how these risks could shape crops, roads and energy infrastructure.

“As we see more extreme events like Sandy, the importance of assessing regional impacts grows,” says lead researcher Adam Schlosser, assistant director for science research at MIT’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change. “Our approach helps decision- and policy-makers balance the risks … so they can better prepare their communities for future impacts climate change might bring.”

For example, Schlosser says, if a community is planning to build a bridge, it should look at — and plan for — the expected magnitude of flooding in 2050.

“In areas devastated by Sandy, the rebuilding of lost property and infrastructure will come at considerable cost and effort,” Schlosser says. “But should we rebuild to better prepare for future storms like these? Or should we prepare for stronger and/or more frequent storms? There remains considerable uncertainty in these projections and that implies risk. Our technique has been developed with these questions in mind.”

Schlosser’s research partner, Ken Strzepek, a research scientist at the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, notes policymakers are now often given little more than a set of extreme circumstances to consider.

“Policymakers don’t like extremes or worst-case scenarios,” Strzepek says, “because they can’t afford to plan for the worst-case scenarios. They like to see what is the likelihood of different outcomes. That’s what we’re giving them.”

Getting results

In this new method, the researchers quantify the likelihood of particular outcomes and add socioeconomic data, different emission levels and varying degrees of uncertainty. Their technique combines climate-model projections and analysis from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and the MIT Integrated Global System Modeling (IGSM) framework. The MIT framework is itself a combined computer model that integrates an economic, human system with a natural, earth system.

“This approach allows us to widen the scope and flexibility of climate analysis,” Schlosser says. “It provides us with efficient capabilities to determine climate-change risks.”

The initial study using this approach — accepted by the Journal of Climate and available on the journal’s website — compares a business-as-usual case with a scenario that reduces emissions. The researchers find that lowering emissions reduces the odds of regional warming and precipitation changes. In fact, for many places, the likelihood of the most extreme warming from the business-as-usual case could be eliminated almost entirely.

The study finds diverse climate-change outcomes: southern and western Africa, the Himalayan region, and the area around Hudson Bay in Canada are expected to warm the most; southern Africa and western Europe see the greatest chance of drier conditions. Meanwhile, the Amazon and northern Siberia may become wetter.

Putting the method to work

Schlosser and Strzepek are pursuing partnerships with communities to put their method to work. But while it’s important for every community to begin building climate adaptation into its infrastructure plans, developing countries could reap the greatest benefits.

Malcolm Smart, senior economic adviser for the U.K. Department for International Development, who was not involved in this research, says, “This is not only an innovative and multidisciplinary approach to the problem of deep uncertainty, but also a potentially very valuable tool to help vulnerable developing countries cut the cost of damages from climate change.”

Strzepek explains why: In the United States, infrastructure plans are designed based on a high standard of risk, while in developing countries projects are typically built to a lower standard of risk. “But if we find that [a developing country] will see greater flooding, and if we’re fairly certain of this, then they would save money in the long run if they built roads to withstand those flooding events,” Strzepek says.

Schlosser and Strzepek traveled to Finland earlier this fall to present their research at a United Nations University-World Institute for Development Economics Research conference. They’ve partnered with this organization to inform developing countries of this new tool for assessing climate change.

“Our approach allows decision-makers to cut down on the level of risk they’re taking when allocating their limited funds to development projects,” Schlosser says. “This can help them see where there are economic benefits to taking a risk-averse approach today, before the damage is done.”

Related research: Climate Change: A Developing Challenge for Poor Nations

By: Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

Susan Solomon, the Ellen Swallow Richards Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Science

Photo: Dominick Reuter

In looking for ways to combat climate change and minimize the planet’s warming, atmospheric chemist Susan Solomon says it’s often helpful — and heartening — to look to the past.

Solomon points out that recent decades have seen major environmental progress: In the 1970s, the United States banned indoor leaded paint following evidence that it was poisoning children. In the 1990s, the United States put in place regulations to reduce emissions of sulfur dioxide — a move that significantly reduced acid rain. Beginning in the 1970s, countries around the world began to phase out leaded gasoline; blood lead levels in children dropped dramatically in response.

During this period, Solomon herself contributed to a milestone in environmental protection: In 1985, scientists discovered that the Earth’s protective ozone layer was thinning over Antarctica. In response, Solomon led an expedition whose atmospheric measurements helped show that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) — chemicals then used in aerosols and as coolants in refrigerators and air conditioners — were to blame for ozone depletion. Her discovery ultimately contributed to the basis for the United Nations’ Montreal Protocol, an international treaty designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out CFCs and other ozone-depleting chemicals.

“I find it tremendously uplifting to look back at how our world has changed,” says Solomon, now the Ellen Swallow Richards Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Science at MIT.

Solomon, a renowned atmospheric chemist who worked for 30 years in Boulder, Colo., at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and as an adjunct professor at the University of Colorado, is continuing her work in climate research at MIT, where she joined the Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences in January. In addition to her research, Solomon is teaching a course, 12.085/12.885 (Environmental Science and Society), exploring how society has tackled a range of past environmental challenges through science, engineering, policy, public engagement and politics.

“I think young people today are growing up at a time when they don’t know that we actually have made tremendous progress on a whole series of past environmental challenges,” Solomon says. “Climate change has been called the mother of all environmental issues … and I think our approach to this problem can only be better informed if we understand better what we’ve done in the past.”

Heading west

Born in Chicago, Solomon was completely taken, from a young age, with “The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau,” a documentary series that followed the legendary marine explorer on his seafaring expeditions. “I pretty much never wavered from the decision right then that I was going to be a scientist,” she recalls.

After high school, Solomon enrolled at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where she received a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. Continuing her studies in atmospheric chemistry, Solomon moved west, to the University of California at Berkeley. “I had a 1977 Gremlin,” Solomon recalls. “It was one of the most awful cars, I think, ever made, but it was really cheap, and I was young and poor. I remember listening to … ‘California Dreamin’’ as I drove out west.”

Solomon received her PhD in chemistry from Berkeley in 1981, and went to work as a research scientist at NOAA. In 1985, scientists with the British Antarctic Survey discovered the ozone hole above Antarctica, prompting Solomon to lead expeditions to the icy continent in 1986 and 1987.

“It’s the next-best thing to going to another planet,” Solomon says of the harsh yet exhilarating experience. “It is the place on our planet that is the most unexplored, the most remote, the most hostile in terms of what the weather and climate is. It is so viciously cold. I just thought it was fantastic exploration, and it’s that spirit of exploration that I think is so endemic to science, and is fundamental to everything about Antarctica.”

In 2001, Solomon chronicled perhaps the most dramatic exploration of that continent in a bestselling book, “The Coldest March”: She used scientific data to examine long-held myths about Robert Falcon Scott, an early-20th-century English explorer who trekked more than 1,000 miles on foot in an effort to become the first to reach the South Pole. But Roald Amundsen, a rival explorer, beat him to the pole by a month, and Scott, along with several team members, perished on the long trek back.

While Scott’s expedition had been ridiculed — for example, by some who painted him as a “dyed-in-the-wool Englishman who only wanted to eat tinned mutton,” and therefore died of scurvy — letters and diaries from his crew told a different story. Many members of the team described eating fresh seal meat and seal liver, which have been shown to be a good source of the vitamins that ward off the disease. Solomon also analyzed weather data from 1912, and discovered that the crew likely would have survived had they not encountered extreme and unpredictable weather conditions.

“It just seemed to me that somebody needed to go back and take a closer look, with all the diaries of all the guys, and what we know from modern science,” Solomon says.

Changing the climate

In 2002, Solomon took on another monumental task: leading an international assessment of the scientific work related to climate change. Over six years, she served as co-chair of Working Group 1 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In 2007, the group released a comprehensive report on the scientific basis of climate change. Later that year, based in part on the report, the IPCC and former vice president Al Gore received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Solomon continues to seek answers to the most pressing climate challenges. In a widely cited 2009 paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Solomon and her co-authors determined that, even if humans were to immediately and completely stop emitting carbon dioxide, it would take more than 1,000 years to undo existing changes in Earth’s surface temperatures, rainfall and sea levels.

This news, while sobering, has not deterred the chemist in her scientific goals. Solomon is currently probing which places on the planet are likely to be the most affected by anthropogenic warming in the near future. In addition to her climate research, she also continues to study the stratosphere — the layer of the atmosphere in which the ozone layer is found.

“There are still fantastic surprises in the stratosphere, as there are in any field, no matter how much has been done on it,” Solomon says. “There’s always something to discover, and I love that feeling.”

Read an earlier story about a lecture Susan Solomon gave.