News + Media

Karplus, Paltsev recieve award for study on the impacts of vehicle efficieny stanards

Valerie Karplus, Research Scientist, and Sergey Paltsev, Assistant Director for Economic Research with MIT’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, were awarded the 2012 Pyke Johnson Award at a ceremony last night during the annual meeting for the National Research Council's Transportation Research Board. The Pyke Johnson Award recognizes the best paper in the area of planning and the environment.

Published in November in the journal Transportation Research Record, the study looks into the new vehicle efficiency standards. The standards are considered one of the landmark environmental achievements of President Obama’s first term, and have been touted as a way to save consumers more than $1.7 trillion at the pump and cut vehicle emissions in half. Karplus and Paltsev look behind the numbers to understand the full energy and economic impacts.

“Common thinking in Washington holds that any policy that seems to advance technology without creating new taxes must be a no brainer for the country. That misses the broader economic impact,” says Karplus. “As my colleague says, you may see more money in your front pocket at the pump, but you’re financing the policy out of your back pocket through your tax dollars and at the point of your vehicle purchase.”

Of the research, University of Maine environmental economist Jonathan Rubin, chair of the Transportation Energy Committee of the Transportation Research Board, says, “The research of Dr. Karplus on the energy and climate impacts of the nation’s fuel economy standards for our cars and trucks makes an important contribution to policy-making based on science.”

The new fuel standards require automakers to install pollution-control technology to improve the fuel efficiency of cars by 5 percent and light trucks by 3.5 percent with each new model year starting in 2017. Karplus and her colleague simulated the proposed standards, and found that while drivers of these more efficient vehicles will no doubt save at the pump, they could spend several thousands of dollars more when buying their new car. Even more troubling, diverting efforts toward improved vehicle efficiency distracts attention away from policies that would target the broader economy and reduce fuel use or emissions more cost effectively, such as a carbon tax.

Estimates of how costly the policy would be – in terms of both direct costs to consumers and the larger rippling costs to the economy – hinge on the relative cost of the technology available to improve efficiency. The shorter the time frame automakers are given to develop the technology and produce more efficient vehicles, the less time there will be for technological progress and other factors to drive down costs and the more consumers will need to pay upfront. Emissions and oil imports will drop – both due to increased fuel efficiency and as the higher vehicle costs weighs on consumer budgets – but will be offset as consumers face lower costs per mile traveled, incentivizing more driving.

Karplus hopes her results will help policymakers make more informed decisions going forward. She credits that to the innovative method she used, which weaves engineering and technology constraints into a broad economic framework and allows researchers to test the cost and other impacts of a policy at different levels of stringency. This method inherently takes account of life-cycle emissions, as well as impacts that transmit across fuel markets by affecting prices. For example, a policy might only consider gasoline use by plug-in electric hybrids, but that “tailpipe measure” doesn’t take into account the emissions created from building, transporting and recharging those batteries. Her approach does.

“There are a lot of hidden costs to a policy like this,” Karplus says. “This model doesn’t allow you to ignore other important aspects of the economy and energy systems. It requires you to be explicit about your technology and cost assumptions. It provides a framework that allows lawmakers to look at all the available information on costs and the state of the technology and decide how to best create or update policies.”

A Win for Energy and America

By John Reilly

THE NEW - STILL DIVIDED - CONGRESS reconvenes this month, and its first order of business is the looming federal deficit. The president made his desires clear in his victory speech: "We want our children to live in an America that isn't burdened by debt . that isn't threatened by the destructive power of a warming planet." Meanwhile, congressional leaders recognize the need for compromise.

Some suggest that closing the deficit would require both budget cuts and increased revenue. The riddle in any tax reform is the need to reduce the tax burdens on wage earners and investors, while generating revenue for essential government services. A carbon tax might answer this riddle. It could help avoid some tax hikes and spending cuts, while stimulating the economy, securing America's energy future, and giving utilities and energy companies greater certainty.

The Congressional Budget Office found that a tax on carbon dioxide, starting at $20 per ton, could raise $1.25 trillion over the next decade. Our research puts those numbers higher - at $1.5 trillion - while cutting emissions by more than 20 percent by 2050. With the money raised, Congress could maintain income tax cuts and avoid serious cuts to social programs.

Lowering taxes and maintaining funding for social programs would give Americans more money to spend, boosting the economy. This is particularly true in the short term, if tax cuts and spending are skewed toward lower income households, which spend more of their income, stimulating weak consumer demand. On the other hand, cutting these programs and raising other taxes would drag down our economy, so much so that the loss would more than offset the cost of a carbon tax.

When it comes to the pure economics, a carbon tax makes the most sense. But what is a win for our economy is also a win for the energy industry. For years, many in the industry have called for a clear, market-based approach to secure America's energy future. Instead, they've received mixed signals and patchwork regulations. Meanwhile, narrow tax incentives have allowed the government - not the market -to choose winners and losers. This approach has been inefficient and ineffective.

A carbon tax, if part of broad tax reform, could bring an end to this approach, providing certainty to utilities and energy companies and allowing these businesses to make the investments needed to usher in America's clean, prosperous and secure energy future. A carbon tax would provide a clear market signal for U.S. businesses and consumers, giving them the flexibility to choose technologies that save energy and money, boosting sales of more fuel-efficient cars and other goods. With greater efficiency, fuel and energy costs could actually go down - not up - as the U.S. economy turns from spending and borrowing to saving and investing in our future.

Partisan gridlock and the political fear of anything labeled a "tax" may make this sensible solution seem impossible. But because it makes the most economic sense, it is receiving support from both sides of the aisle.

As the chairman of President George W. Bush's Council of Economic Advisers, Greg Mankiw, has said, "Economists have long understood that the key to smart environmental policy is aligning private incentives with true social costs and benefits. That means putting a price on carbon emissions, so households and firms will have good reason to reduce their use of fossil fuels and to develop alternative energy sources." There are usually hefty trade-offs and hard-set winners and losers in politics. This time, that doesn't have to be the case.

Get the inside scoop and follow LIVE reports from Geneva by twitter and blog.

Ten MIT students are having an experience of a lifetime as they join officials from around the world for the fifth and final meeting to address global controls on mercury – taking place January 13-18 in Geneva, Switzerland. It is expected that a global treaty on mercury will be finalized during the talks.

Funded through part of a U.S. National Science Foundation grant, the students hope to help negotiators by presenting the latest scientific results (See more).

The students will be reporting on the progress of the talks and their experiences on their blog. Keep updated on the day-to-day action: mit.edu/mercurypolicy.

They’ll also be tweeting LIVE from Geneva. Follow them @MITMercury, #MITMercury.

They are joined by their instructor Noelle Selin, an assistant professor of engineering systems and atmospheric chemistry. Of the experience, Selin says: “Knowledge about the policy-making process is a critical skill for the next generation of scientists. This is a unique opportunity for science students to see treaty-making firsthand, at the history-making session that is expected to finalize a global mercury treaty.”

Student Leah Stokes, a PhD candidate in MIT’s Environmental Policy and Planning program says, "Attending the mercury treaty negotiations is a rare chance to see international environmental policy-making in action and learn how scientists and policymakers work together to produce results.”

Fellow student Julie van der Hoop, who is getting her doctorate in the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography, adds, "As a doctoral student who studies human interactions with marine mammals, I’m excited to observe the role of scientists at these negotiations to learn how to best share my own research in the future. It's forums like this where I hope my work will have an impact someday. “

The other students attending include: Alice Alpert, PhD student in the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography; Ellen Czaika, PhD candidate in the Engineering Systems Division; Bethanie Edwards, PhD student in the MIT/WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography; Amanda Giang, SM candidate in the Technology and Policy Program; Danya Rumore, PhD student in Environmental Policy and Planning; Rebecca Saari, PhD Candidate in Engineering Systems; Mark Staples, SM candidate in the Technology and Policy Program; and Philip Wolfe, PhD Candidate in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Learn more about the students and their instructor Noelle Selin Here.

Learn about the latest mercury research out of MIT: Strategies to Reduce Mercury Revealed Ahead of International Talks.

Harvard, MIT researchers map future trends of mercury and ways to reduce it on eve of international negotiations.

International negotiators will come together next week in Geneva, Switzerland for the fifth and final meeting to address global controls on mercury. Ahead of the negotiations, researchers from MIT and Harvard University are calling for aggressive emissions reductions and clear public health advice to reduce the risks of mercury.

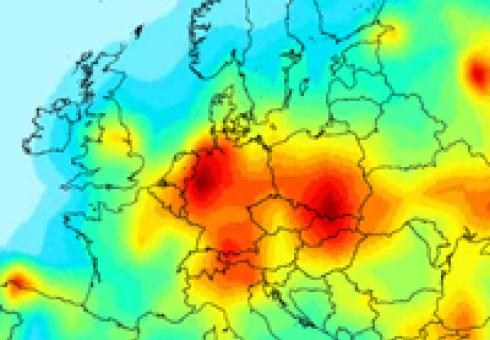

The researchers’ commentary, published this week in the journal Environmental Health, is in response to a study on the costs associated with mercury pollution in Europe. That study showed that as many as two million children in European Union nations are born each year with long-term IQ deficits due to unsafe levels of mercury exposure. These lower IQs can have spiraling effects on the earning potential of those impacted down the road, resulting in as much as 9,000 million euros in lost revenue a year.

But the authors of the commentary, Elsie Sunderland of Harvard and Noelle Selin of MIT, say mercury’s impact — and that of its toxic form methylmercury — extends far beyond the EU.

“Mitigating the harm caused by methylmercury requires global-scale cooperation on policies and source reductions,” Sunderland says.

Fish and other species, such as polar bears, can be harmed by mercury exposure. Once entered into the food chain, this exposure harms humans. In the near term, the public health community can advise changes in seafood consumption to control the risks, the researchers say. The critical action, however, comes in making significant progress in reducing mercury emissions to prevent an even greater increase in cycling “legacy” emissions.

“Most analyses forecasting mercury levels underestimate the severity of the situation because they don’t take the entire picture into account when looking at future mercury levels,” says Selin, an assistant professor of engineering systems and atmospheric chemistry.

Selin and Sunderland explain in their commentary that most mercury exposure comes from eating fish. Coal-fired power plants and other sources such as industrial activities emit mercury to the atmosphere. This mercury eventually rains down to the land and sea. In the ocean, mercury can convert to toxic methylmercury, and accumulate in the marine food chain. Mercury pollution settles deep within the ocean and circulates for decades and even centuries, continuously posing dangers to humans and the environment.

When considering future emissions, these “legacy” emissions are often not taken into account, but should be, the researchers say, because they make up a substantial amount of future emissions and could make already-dangerous levels of mercury even more threatening.

For example, mercury in the North Pacific Ocean — a large player in the global seafood market — is expected to double by 2050, from 1995 levels, due to new emissions. With the substantial “legacy” emissions that will circle back into the atmosphere, that amount is much greater. This increase in mercury could have dire impacts on fish from the Pacific Ocean.

“Not only will we see these ‘legacy’ emissions circle back up,” Selin says. “But with energy demands growing worldwide, we’ll see more new mercury entering the atmosphere, unless we act now to control this mercury at its source — and that’s largely coal-fired power plants.”

Sunderland and Selin say the United Nations Environment Program’s negotiations represent a sure step in the right direction. The question is: Will the talks produce real results?

In an interview with MIT News just prior to the first negotiating session in 2010, Selin said U.S. domestic politics would likely be a challenge to international cooperation on mercury. But last year, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency finalized Mercury and Air Toxics Standards that require coal-fired power plants to install scrubbing technology that will cut 90 percent of their mercury emissions by 2015. With these standards — now the most stringent mercury standards of their kind in the world — Selin says the country has proven its leadership and provided some hope.

“These standards show that the U.S. is taking leadership at home to address a widespread and substantial global problem,” Selin says.

Selin, along with ten MIT graduate students, will present recent scientific results to negotiators in Geneva next week.

By: Vicki Ekstrom

MIT researchers enhance model to assess the risks of water stress. A conflict over water management has intensified along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Downstream states argue water should be released from the Missouri’s upstream reservoirs into the Mississippi to allow shipping to continue in the record low-level waters. Upstream states are fighting to keep the water to irrigate their crops and prevent the drought from getting even worse next year. To add to the tension, still others want to move a portion of the Missouri River Basin’s water to the Colorado Basin—which will see demand outstrip supply in the coming decades, according to a federal study released last week.

A conflict over water management has intensified along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Downstream states argue water should be released from the Missouri’s upstream reservoirs into the Mississippi to allow shipping to continue in the record low-level waters. Upstream states are fighting to keep the water to irrigate their crops and prevent the drought from getting even worse next year. To add to the tension, still others want to move a portion of the Missouri River Basin’s water to the Colorado Basin—which will see demand outstrip supply in the coming decades, according to a federal study released last week.

These are the stakes in the conflict over water, and the impacts could be profound and widespread. Agriculture, river navigation, energy and other industries all stand to lose as populations increase and the possible side effects of climate change emerge. To measure future changes on water resources, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have enhanced their global model to include a new tool that assesses the risks of water stress.

“As fresh water sources throughout the world experience considerable stress because of an increasing population, economic growth, and droughts, floods and other climate effects, this tool will provide valuable insights to industries and communities competing for water,” says Ken Strzepek, a researcher at the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, who helped design the tool.

Strzepek and his colleagues Adam Schlosser and Élodie Blanc take population, GDP and other socio-economic factors and combine them with hydro-climatic information such as precipitation and runoff from their earth system model. They then combine this information to estimate changes in demand across sectors such as public and private water use, agricultural use and thermoelectric cooling used in energy production. The result is an expanded model that can forecast if and where there could be stresses within water basins, along with the risks surrounding those changes.

“Globally, the tool is helping us see where the hot spots for water stress are and where might that stress increase in the future due to human growth and climate change—two factors that are coming together and exacerbating the problem of water management,” says Schlosser, the assistant director of science research at the Joint Program on Global Change.

While the new model paints the picture globally, it can also be applied at a regional and even local scale to help communities make important decisions about their future energy investments, infrastructure plans and adaptation strategies. Uniquely, by incorporating risk and uncertainty, the model helps policymakers evaluate the question: What investments do we need to make to be better prepared?

“When looking at different climate models, not only do they show different results, they show different directions—one shows a positive change where another might show a negative change,” Schlosser says. “However, our technique allows us to quantify this uncertainty as risk to help decision makers formulate more robust investment plans.”

The researchers have already begun to apply their model to the U.S. While their findings are still being written, the researchers agree that critical water management issues will arise—and in some areas are already emerging. They are finding that the areas that will see the greatest stress going forward are the same places where very rigid water management laws already exist, such as around the Missouri, Mississippi and Colorado rivers.

“Our model framework is able to account for water management and allocation policies,” Schlosser says. “This allows us to take a situation like transferring water from the Missouri to the Colorado Basin and assess the impacts to both basins going forward.”

Drawing from this measure of risk, the researchers warn that decision makers in developing countries should make their adaptation plans both flexible and efficient.

“If we don’t know how much water will come down the river, we should design dams to be constructed in stages. For example, we should make provisions to add hydropower generation capacity easily and accordingly. ” Strzepek says. “We need to have flexible designs, and also efficient designs, so we’re building in a way that the structure will perform well under a variety of climates.”

Read more about the new tool here.

By: Alvin Powell, Harvard Staff Writer

Benefits, risks of using geoengineering to counter climate change.

If they wanted to, nations around the world could release globe-cooling aerosols into the atmosphere or undertake other approaches to battle climate change, an authority on environmental law said Monday. He recommended international discussions on a regulatory scheme to govern such geoengineering approaches.

If they wanted to, nations around the world could release globe-cooling aerosols into the atmosphere or undertake other approaches to battle climate change, an authority on environmental law said Monday. He recommended international discussions on a regulatory scheme to govern such geoengineering approaches.

Under international law, nations can research and deploy such approaches on their own territory, on that of consenting nations, and on the high seas, said Edward Parson, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. Despite that freedom, research into climate engineering remains stalled while opposition from environmental groups, fearful of unintended consequences, is growing,

Parson gave an overview on the policy challenges of climate engineering during a talk titled “International Governance of Climate Engineering” at the Science Center Monday evening. The session was part of a new series co-sponsored by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.

Although several geoengineering approaches are feasible, Parson focused on one he said could be deployed most rapidly: spraying cooling aerosols high into the atmosphere. Nature has already proven such an approach to be effective. When volcanoes erupt, they spew sulfur compounds that reflect the sun’s radiation. Large eruptions can result in global-cooling events, volcanic winters lasting up to several years.

The approach would be fast and cheap but imperfect, Parson said. Aerosols could be sprayed from airplanes relatively inexpensively, for billions of dollars, with costs dropping. It would be an imperfect approach, Parson said, because although spraying aerosols would cool the Earth, it would not be a permanent fix. The effort would do nothing to stop the driving forces of warming: the emission of greenhouse gases. Also, the tactic would last only a year or two, and it wouldn’t address climate change’s other effects, such as acidification of the oceans and ecological changes.

Still, Parson said, the effort could mitigate climate effects that are rapidly worsening, or, more strategically, it could “shave the peak” from the worst warming while the world transitions to low-carbon energy, or it could be employed on a regional scale to mitigate localized problems, such as limiting the melting of sea ice during the Arctic summer or reducing sea surface warming in the regions where hurricanes form.

Of course, the prospect of such offbeat approaches also raises the specter of incompetent, negligent, or even malicious uses, Parson said. One of the largest potential threats involving climate engineering could come from nations’ militaries looking to ease domestic conditions at a neighbor’s expense.

International regulations could be drafted by the dozen or two dozen nations capable of carrying out such programs, Parson said. He suggested that such regulations should ban research that might have large-scale impact while allowing more responsible, smaller-scale work to proceed. He also advocated requirements for transparency and disclosure of results.

Parson said it is important to find out whether climate-engineering techniques can have a regional or global impact, and how much they might be fine-tuned to address local or regional problems. It also will be important to determine where nations’ interests lie. If their goals are aligned, he said, creating and executing a regulatory scheme will be far easier to do.

Though it may be difficult to get intransigent nations to the table, as their fear over climate change rises, so will their willingness to negotiate, he suggested.

“Nothing is politically impossible, contingent on the current level of alarm,” Parson said.

View picture from the event on our facebook page here.

Stay tuned for the next event here.

By: Kate Galbraith

AUSTIN, TEXAS — The harm that can be caused by consuming or breathing mercury is well known and terrible. A pregnant woman, eating too much of the wrong kind of fish, risks bearing a child with neurological damage. Adults or children exposed to mercury can experience mood swings or tremors, or sometimes even respiratory failure or death.

In January, representatives of dozens of countries will gather in Geneva to discuss combating mercury emissions, which are rising in Asia even as Europe and the United States have tightened controls. The meeting is the last of five negotiating rounds — the first took place in 2010 in Stockholm — and a legally binding treaty on mercury contamination is expected to come together next year.

The signing of that treaty is set to take place in the Japanese city of Minamata, where widespread mercury poisoning occurred in the mid-20th century after discharges from a factory contaminated the seawater.

But the extent to which countries will commit to reducing mercury, and whether they will follow through on those commitments, are open questions.

“What remains to be seen is the stringency of the requirements,” said Noelle Eckley Selin, an assistant professor of engineering systems and atmospheric chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The negotiations “appear to be going in the direction of voluntary compliance,” said Leonard Levin, an air quality specialist with the Electric Power Research Institute, a nonprofit organization with headquarters in Palo Alto, California.

The negotiations in Geneva are being conducted under the auspices of the U.N. Environment Program and are to be followed in the summer by a major conference on mercury in Edinburgh, where scientists and policy makers will discuss how to implement a treaty.

Roughly one-third of the world’s mercury air emissions come from human activity, like coal-fired power plants. Another third of emissions come from natural sources, like volcanoes or wildfires, and the final third are “re-emitted” after their initial release.

Within the human-generated category, Asia contributes nearly 50 percent of mercury emissions, with North America at 7 percent and Europe and North Africa at 12 percent combined, according to Jerry Lin, a professor of environmental engineering at Lamar University in Texas. In addition to coal-fired power plants, a major source of mercury emissions is small-scale gold mining. Miners working on their own often use mercury to help extract gold and then boil it off, leaving behind dangerous contamination.

The effects of mercury contamination are not limited to the local environment. Mercury finds its way into the sea, affecting fish like bluefin tuna, and airborne emissions can travel between continents.

“The mercury today will continue to circulate in the system for a long time,” Dr. Selin said. “We’re talking decades to centuries.” Methyl mercury, the toxic form, even poses a substantial problem for the Arctic, she said, because it can accumulate in polar bears and seals.

Meanwhile, research into the health consequences of mercury “has been finding adverse effects at lower and lower exposures,” Philippe Grandjean, chair of environmental medicine at the University of Southern Denmark, said in an e-mail. New research has found that some people may be more sensitive to the effects of mercury, he said, because of factors like genetics.

The European Union has moved aggressively to combat mercury exposure. A ban on mercury exports began in 2011, and the Union has issued rules on storing mercury and restrictions on some products containing mercury, like thermometers. It is currently considering additional rules on mercury in dental fillings and batteries.

Sweden has “been really out in front” on national mercury regulations, Dr. Selin said. The country banned mercury from dental fillings and other products several years ago.

Starting in January, the United States will ban the export of elemental mercury, whose uses include gold mining. (The ban covers the Department of Defense and the Department of Energy, which keep large stockpiles.) The new policy results from the Mercury Export Ban Act of 2008, which was introduced by two senators — including Barack Obama, who represented Illinois at the time — and was signed into law by President George W. Bush.

In another key mercury development, last year, the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States completed its first rule aimed at mercury emissions from coal plants. The effect on the power industry is unclear, however.

The mercury limits are “probably achievable for existing plants,” said Mr. Levin of the Electric Power Research Institute. Additional rules, not yet completed, would cover emissions from new coal plants, and their effect is still being evaluated, he said.

Other regulations in the United States have also affected coal plants. Controls required for pollutants like nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide can also reduce mercury emissions, as a “co-benefit.”

For China, which is building new coal-fired power plants at a rapid rate, such “co-benefits” could prove crucial, said Dr. Lin of Lamar University. That is because it would be economically difficult to control only for mercury.

By:Elizabeth Kolbert

It’s been almost a century since the British economist Arthur Pigou floated the idea that turned his name into an adjective. In “The Economics of Welfare,” published in 1920, Pigou pointed out that private investments often impose costs on other people. Consider this example: A man walks into a bar. He orders several rounds, downs them, and staggers out. The man has got plastered, the bar owner has got the man’s money, and the public will get stuck with the tab for the cops who have to fish the man out of the gutter. In Pigou’s honor, taxes that attempt to correct for this are known as Pigovian, or, if you prefer, Pigouvian (the spelling remains wobbly). Alcohol taxes are Pigovian; so are taxes on cigarettes. The idea is to incorporate into the cost of what might seem a purely personal choice the expenses it foists on the rest of society.

One way to think about global warming is as a vast, planet-wide Pigovian problem. In this case, the man pulls up to a gas pump. He sticks his BP or Sunoco card into the slot, fills up, and drives off. He’s got a full tank; the gas station and the oil company share in the profits. Meanwhile, the carbon that spills out of his tailpipe lingers in the atmosphere, trapping heat and contributing to higher sea levels. As the oceans rise, coastal roads erode, beachfront homes wash away, and, finally, major cities flood. Once again, it’s the public at large that gets left with the bill. The logical, which is to say the fair, way to address this situation would be to make the driver absorb the cost for his slice of the damage. This could be achieved by a new Pigovian tax, on carbon.

In the past several weeks, as New York and New Jersey have continued to dig out from under the debris left by Hurricane Sandy, the possibility of a carbon tax has come to seem more likely than ever, that is, not very likely, but also not entirely out of the question. The reason for this is not so much the terrible cost of the storm, now estimated at more than sixty billion dollars. (The other day, Governor Andrew Cuomo said that Sandy had caused forty-two billion dollars’ worth of damage in New York State alone.) It’s that, as Washington edges toward the fiscal cliff, it has become obvious to just about everyone, except maybe House Republicans, that Washington needs more revenue.

Not long ago, the Congressional Research Service reported that, over the next decade, a relatively modest carbon tax could cut the projected federal deficit in half. Such a tax would be imposed not just on gasoline but on all fossil fuels—from the coal used to generate electricity to the diesel used to run tractors—so it would affect the price of nearly everything, including food and manufactured goods. To counter its regressive effects, the tax could be used as a substitute for other, even more regressive taxes, or, alternatively, some of the proceeds could be returned to low-income families as rebates (although, of course, this would cut down on the amount that could go toward deficit reduction).

Shortly after the C.R.S. report came out, the conservative American Enterprise Institute teamed up with its liberal counterpart, the Brookings Institution, to host a seminar on the subject, a collaboration that prompted the Wall Street Journal’s Web site to declare, “CARBON TAX IDEA GAINS WONKISH ENERGY.” “I think the impossible may be moving to the inevitable without ever passing through the probable,” Bob Inglis, a former Republican representative from South Carolina and a carbon-tax backer, told the Associated Press.

Perhaps because a carbon tax makes so much sense—researchers at M.I.T. recently described it as a possible “win-win-win” response to several of the country’s most pressing problems—economists on both ends of the political spectrum have championed it. Liberals like Robert Frank, of Cornell, and Paul Krugman, of Princeton, support the idea, as do conservatives like Gary Becker, at the University of Chicago, and Greg Mankiw, of Harvard. (Mankiw, who served as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush and as an adviser to Mitt Romney, is the founding member of what he calls the Pigou Club.) A few weeks ago, more than a hundred major corporations, including Royal Dutch Shell and Unilever, issued a joint statement calling on lawmakers around the globe to impose a “clear, transparent and unambiguous price on carbon emissions,” which, while not an explicit endorsement of a carbon tax, certainly comes close. Even ExxonMobil, once a leading sponsor of climate-change denial, has expressed support for a carbon tax. “A well-designed carbon tax could play a significant role in addressing the challenge of rising emissions,” a spokeswoman for the company said recently in an e-mail to Bloomberg News.

One key player who has not embraced the idea is Barack Obama. The White House spokesman, Jay Carney, was asked about the tax last month, en route, as it happens, to visit storm-ravaged areas of New York with the President. “We would never propose a carbon tax, and have no intention of proposing one,” Carney told reporters. This was taken by some to mean that Obama was opposed to the tax and by others to mean just that he was not going to be the one to suggest it.

In either case, the White House is making a big mistake. Pigovian taxes are rarely politically popular—something they have in common with virtually all taxes. But, as Obama embarks on his second term, it’s time for him to take some risks. Several countries, including Australia and Sweden, already have a carbon tax. Were the United States to impose one, it would have global significance. It would show that Americans are ready to acknowledge, finally, that we are part of the problem. There is a price to be paid for living as we do, and everyone is going to get stuck with the bill.

By: David Frum

Editor's note: David Frum, a CNN contributor, is a contributing editor at Newsweek and The Daily Beast. He is the author of eight books, including a new novel, "Patriots," and his post-election e-book, "Why Romney Lost." Frum was a special assistant to President George W. Bush from 2001 to 2002.

Global emissions of carbon dioxide hit a record high in 2011, scientists from the Global Carbon Project reported last week.

Another record is expected in 2012.

The earth continues to warm, and to warm fast, with serious consequences for human life and welfare. 2012 saw the worst drought in the United States in half a century. Russia suffered its second bad drought in three years. Climatic shocks to these two countries are raising food prices worldwide, posing an especially acute threat to the world's poorest. Major storm events strike harder and more often, because warming oceans create conditions for fiercer hurricanes.

The New York Times reported Friday:

"Emissions continue to grow so rapidly that an international goal of limiting the ultimate warming of the planet to 3.6 degrees, established three years ago, is on the verge of becoming unattainable."

This ominous news arrives as delegates gather in Doha, Qatar, for the latest annual round of climate talks sponsored by the United Nations. Few expect the Doha talks to produce much decision.

Yet there is good news on the environmental front, important news.

Carbon emissions in the United States have declined since 2009 -- not emissions per person (those have been declining for decades), but emissions in absolute terms. The weak economy explains part of the decline, but the real hero of the story is the natural gas fracking revolution.

A decade ago, half of all the electricity generated in the United States was generated by burning coal, the most carbon-dense fuel of them all. Today, coal's share of the electricity mix has plunged to one-third, as utilities substitute cheap natural gas. Gas production has become much cheaper with the growth of fracking -- forcing open rocks by injecting fluid into cracks. Gas emits about half as much carbon per unit of energy as coal.

Environmentalists have responded warily to the advent of gas. They prefer zero-emissions power sources like wind and solar -- sources made more uncompetitive than ever by ultracheap natural gas. (Today's price: about $3.50 per thousand cubic feet, down about 70% from the prices of the mid-2000s.)

Moreover, natural gas does little (as yet) to address emissions from automobile tailpipes.

But maybe there's a way to cheer environmentalists up. Take three worrying long-term challenges: climate change, the weak economic recovery, and America's chronic budget deficits. Combine them into one. And suddenly three tough problems become one attractive solution.

Tax carbon. A tax of $20 a ton, rising at a rate of 4% per year, would over the next decade raise $1.5 trillion, according to an important new study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. That $1.5 trillion is almost twice as much as would be recouped to the Treasury by allowing the expiration of all Bush-era tax cuts for upper-income taxpayers.

The revenues from a carbon tax could be used to reduce the deficit while also extending new forms of payroll tax relief to middle-class families, thus supporting middle-class family incomes.

Meanwhile, the shock of slowly but steadily rising prices for fuel and electricity would drive economic changes that would accelerate U.S. economic growth.

The average age of U.S. cars and trucks has reached nearly 11 years, a record.

Millions of Americans want new cars. They are waiting for market signals as to what car to buy. They want to know that if they choose a fuel-efficient vehicle, they won't feel silly three years from now when their neighbor roars past them in a monster truck because gas has plunged back to $2 a gallon.

After five years of depression, the housing market is also ready for renewal. Again, Americans are waiting for market signals: Should they buy smaller houses nearer to work? High and rising fuel prices will encourage developers to build more mixed-use complexes that allow more people to live car-free: walking to work, entertainment, and shopping. The surest way to reduce fuel costs is to drive less.

The return to more urban living is a trend big enough to sustain America's next great economic boom. To the extent researchers can measure, the daily commute appears to be the single worst recurring source of unhappiness in American life.

If changes in city shape can offer more Americans the opportunity to walk to work through an attractive shopping mall, rather than waste 50 minutes in a car in a traffic jam, those changes will advance human happiness, spur new construction work, and incidentally save the planet.

A carbon tax will also enable the United States and Europe to press China and India to reduce their carbon emissions. A properly designed tax would apply not only to domestic goods and services, but to imports as well.

China and India would discover that their products no longer seem so cheap when a carbon tax at the border adds back the environmental costs of dirty manufacturing. To export to the world's richest consumers, China and India will have to clean up their act -- an incentive more persuasive than a hundred Doha conferences.

More jobs and growth; reduced deficits without raising income taxes; lower taxes for middle-class families; a kick in the pants to Chinese polluters; and more happiness for American commuters -- one policy instrument can do it all. What's not to love about a carbon tax?

By: Vicki Ekstrom Fatih Birol, chief economist of the International Energy Agency (IEA), visited MIT on Wednesday, November 28 to present this year’s World Energy Outlook. While on campus, Birol met with researchers at the Joint Program on Global Change to learn about the latest developments on climate change policy and MIT’s Emissions Predictions and Policy Analysis (EPPA) model. The model is used by MIT researchers to make their own world economic and emissions projections.

Fatih Birol, chief economist of the International Energy Agency (IEA), visited MIT on Wednesday, November 28 to present this year’s World Energy Outlook. While on campus, Birol met with researchers at the Joint Program on Global Change to learn about the latest developments on climate change policy and MIT’s Emissions Predictions and Policy Analysis (EPPA) model. The model is used by MIT researchers to make their own world economic and emissions projections.

“We had a very productive discussion about the future of the world’s energy system development and advances in modeling alternative pathways. We also shared information about our current projects and future directions,” said Sergey Paltsev, assistant director for economic research at the MIT Joint Program on Global Change, after the meeting. “IEA’s World Energy Outlook is one the most comprehensive and authoritative sources in energy projections and related carbon emissions.”

Birol also commented on the usefulness of the exchange:

"As our World Energy Outlook 2012 shows, the global energy system is undergoing fundamental, rapid change. MIT's proven, interdisciplinary approach to research and education in energy and climate issues will be even more important in the years to come,” Birol said.

Named by Forbes magazine as one of the most influential people on the global energy scene, Birol chairs the World Economic Forum’s Energy Advisory Board and is often called on to brief high-level political figures — including President Barack Obama.

Birol’s meeting with Paltsev, along with MIT Global Change researchers Henry Jacoby and Valerie Karplus, came prior to an MIT Energy Initiative-hosted event on the IEA’s World Energy Outlook. The Outlook projects that the United States will become the world’s leading oil producer within a few decades, while gas will continue to be a major player. It also turns attention to climate change.

“As each year passes without clear signals to drive investment in clean energy, the ‘lock-in’ of high-carbon infrastructure is making it harder and more expensive to meet our energy security and climate goals,” said Birol when IEA released the Outlook on November 9.

The Outlook finds that four-fifths of the total energy-related carbon emissions permitted under a scenario that limits warming to 2°C, the globally-agreed goal, are already locked-in by existing capital stock such as power stations, buildings and factories. It warns that without further action by 2017, the energy-related infrastructure in place would generate all the carbon emissions allowed up to 2035. Delaying action is a false economy, the report says, noting that for every $1 of investment in cleaner technology that is avoided in the power sector before 2020, an additional $4.30 would need to be spent after 2020 to compensate for the increased emissions.

Read more about the Outlook in a special MIT News interview with Fatih Birol here.